Leeds author: What I’ve learnt from weeks of living under lockdown in Spain

At one minute to eight it begins. Spain is not a country known for its punctuality, but you could set your watch by this. It’s not just on time; it’s ahead of time. Every evening we open the windows just before eight and applaud, along with millions of others, for several minutes.

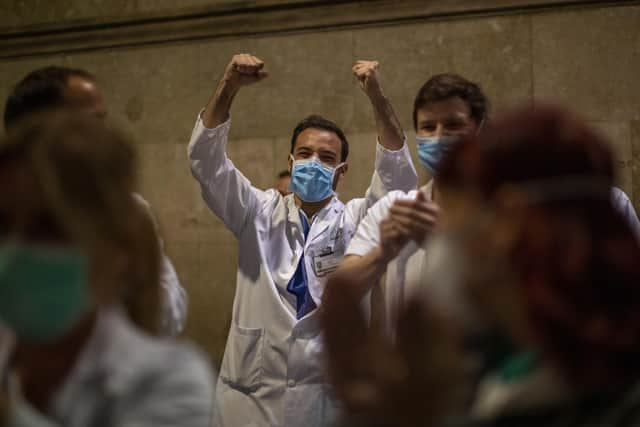

As the lockdown here moves towards its third week, the urge to do something in praise of the country’s health workers becomes stronger.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs I write this, around a seventh of them have contracted the virus. Doctors and nurses, many of the young and healthy, have already died. We know that more will follow. And we know that it is because these people being obliged to do their jobs without masks or adequate protection from the virus, as the government scrambles to keep up in what is now one of the epicentres of the pandemic.

So people lean out of the windows and clap. I watch the faces of neighbours in flats across the street and I feel proud, but also a bit awkward, a bit daft. But it’s not pointless. Videos of this applause are reaching health workers, who are sending back innumerable thumbs-up images and videos of thanks on social media.

And that, I think, is what it’s about: the need to do something together, even when it’s little more than a daily acting-out of one’s own helplessness and gratitude.

Spain is big on communal action. Solidarity still counts for something here; large, peaceful demonstrations in the streets in response to a terrorist atrocity or in support of one good cause or another.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIndeed, the painful irony is that Madrid, where overrun hospitals are now treating patients on floors and in corridors, and where the dead lie in a converted ice rink, is probably a victim of this sense of solidarity.

A march to celebrate International Women’s Day was allowed to go ahead in Madrid on March 8, just as the epidemic was taking hold. 100,000 people attended.

Lots of arm-linking, lots of hugging and kissing on both cheeks.

Spain, and of course Italy, are countries in which human contact is simply more prevalent and more significant than in Europe’s personal-space-loving north.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNone of that now, though. The rules on confinement are being followed pretty well. Up here, on the fifth floor, we haven’t been out at all for a fortnight (I have a persistent cough, not thought to be Covid-19, but we’re all coughing a bit now, so we’re just keeping out of the way).

Down on the street below we see the occasional person scurrying home from the supermarket, where only ten people are allowed in at a time, and social-distancing queues spread around the block from shortly after opening time.

There are certainly worse things than a family of four living in isolation in a two-bedroom flat with running water and enough food.

It is, perhaps, this sense of it all being eminently survivable, nothing much more than a niggling, surreal few weeks, that jars with the knowledge that hundreds are dying each day, that nurses are tending to the sick in the knowledge that they might be next, that our days are punctuated by events beyond our control.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdApart from the clapping in the evening, the most important daily routine is watching for the morning’s tally of new cases and fatalities.

It’s horrific, but also slightly off-stage, a drama playing out around us but not (thus far) involving us.

Meanwhile, the various practical issues seem trivial, but they never stop. Teachers are desperately trying to keep classes going online, sending their students a never-ending stream of worksheets, links, websites... Then there’s adult work, mine and my partner’s, which again is being done online.

But what happens when you have no more paper for printing stuff out? Or no more printer ink? In our house we have two functioning laptops for four people, we are all trying to maintain our daily rhythm of study or work online. If a laptop gets damaged, 50 per cent of our capacity to work and study vanishes. If our internet stops working, that’s 100 per cent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt wouldn’t matter. We’d carry on. It won’t be forever. But for some it might be. One of our sons is now having his saxophone class via Skype. The owner of the private music school asked if we could take a picture of the class and let him use it on their Facebook page.

Most pupils have simply cancelled classes, and the school is losing money, its dozen free-lance teachers going unpaid. How long can that last? How much debt can a small business afford to accumulate? We don’t know.

Meanwhile, two elderly sisters that my partner’s family know live about a mile away in a fourth-floor flat. They are both in their eighties, and one is bed-ridden and has severe dementia.

Her sister was just taken into hospital with a respiratory infection and is being kept in isolation. Meanwhile, the other one is being visited by a health worker for part of the day and night, and left alone in her bed the rest of the time. We can do nothing to help. So we clap. It is, literally, the best that we can do.

John Barlow’s latest novel, The Communion of Saints, is out now.