A Yorkshire Year: The new book taking a sideways look at Yorkshire's incredible history

One of the fascinating things to discover from a published author – and one of the most frequently asked questions – is “Well, how long did it all take?”

Was the new book, pamphlet, or even a newspaper or magazine feature, swiftly committed to the laptop, or old-fashioned paper? Did it take hours, days, weeks, of labour-intensive commitment, or did the idea, the concept, just pop into the writer’s head?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

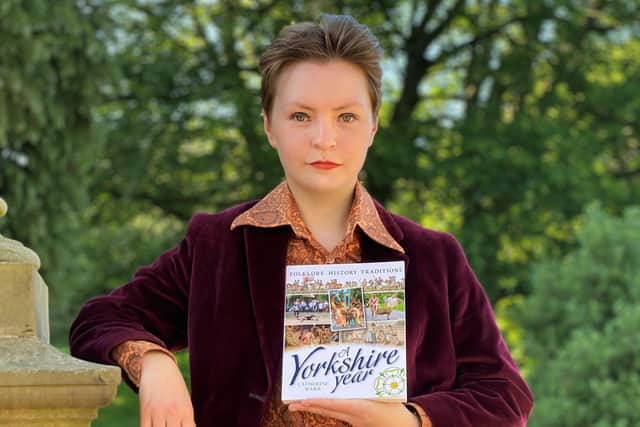

Hide AdWriter Catherine Warr, it seems, has a unique answer. Her new book, A Yorkshire Year, took forever. Or at least, as far back as she started to take an interest in history and our environment. Which is around twenty years ago, and when she was a little girl.

Catherine, 24, was born, raised, and still lives, in Leeds, and was always being taken out “to see castles, and stately homes, things like that, for as long as I can remember. I was always a precocious reader, and it seemed to me, then as now, that no opportunity was missed for us to get out of the house, and to go and explore. Writing A Yorkshire Year was definitely helped by the fact that I seem to have a very good memory!”

Indeed, one of her recollections is still vivid. “I must have been about five or six, and we went over to South Yorkshire, and happened to be at Conisbrough Castle very early in the morning. So much so that we were the first people there.

"And the very genial man who was one of the custodians there (it’s a hugely popular English Heritage property) asked me if I’d like to turn the key to the main door, so that it was fully open to the public. What a thrill that was, and I remember the privilege so well.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo the point, says Catherine, that she now believes that her writing will be – hopefully – a key for others to get out there and to discover all sorts of facts and figures about this county of ours, so abundant in heritage and happenings, locations and lore.

Catherine laughs: “I think that I was also inspired, in some way, by discovering the Horrible Histories books and TV series. It’s interesting, isn’t it, that there are many of us, youngsters as well as adults, who are far more entertained by the information about the hangings and drawings and quarterings, the poor old women dumped ingloriously into a pond when accused of witchcraft or whatever, and where our ancestors went to the loo, than those who enjoy reading about princesses and pageantry?”

So, Yorkshire Year took some three or thereabouts to pull together into published form, but was a lifetime in the making. It’s a day-by-day calendar account of events which, across the centuries and the millennia, which have shaped the county.

There are anniversaries, remarkable occurrences, traditions celebrated on set days, recipes which are pertinent to the times of the year or to great events. A cornucopian kaleidoscope that refused to be defined by a single title. Anthology is probably the best word.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCatherine’s parents were always fascinated by antiquarian books and publications, and their passion has rubbed off on their daughter, who is never happier than trying to track down the background to so many diverse subjects.

She’s found out that “Victorian priests, probably with more than a little time on their hands” were some of the best chroniclers of the world around them – especially when it comes to recording folklore. The Rev. S Baring-Gould, who was for a while the Vicar of Horbury, near Wakefield, noted down a song in 1864 which was sung tom him one day by some mill lasses. The first two verses run:

I am a jovial heckler boy

And by my trade I go;

I trudge the world all over

And get my living so.

I trudged this world all over,

A pretty maid I spied,

I asked if she would go with me

And be my lawful bride.

The romance progresses quickly. Catherine does not spell out what the profession of ‘heckler’ might involve, but it turns out that ‘heckler’ is an alternate version of ‘hackler’, a person who uses a hackle to blend, or straighten flax. And a hackle is a metal plate with rows of very sharp needles. Think of a very dangerous afro-comb.

“The pleasure for me”, says Catherine, is to get readers to explore further. So, I take them, I hope, into unknown territory, and beyond things that they already know. Like the Bronte sister. Everyone knows quite a lot about them, and there’s really little for me to add.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"Their dissolute brother Bramwell, however, is quite another matter – to me, he’s the strangest of those Howarth children, and by far the most interesting in his relative obscurity, and his being a true misfit. The ‘Bronte tea towel economy’ just bores me to tears!”

And then she adds, with a laugh: “I’m sick of the |Tudors, as well. Every TV documentary has someone in the Tower of the London, and dressing up. Enough, please, enough!”

She is forthright about the places that she calls “tourist traps”, and names quite a few, York Minster among them. “Go once or twice, and most people will know it quite well. But it’s in the places like that, and which are ‘behind the scenes’, that always grab me. The gargoyles and carvings in the roof of Beverley Minster, which few will discover, for instance. These hold the really interesting history of the place.”

Only a few weeks back, she says, “I was in Leeds Minster, and which I thought that I knew reasonably well, but I had a little ramble, and looked a=very carefully at some of the memorials, so easy to pass by. And from just that, I learned far more than I ever thought about this beautiful church, tucked inconveniently behind the bus station.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd she also prefers folk history that is “genuine, and not twee”. When she writes about the abundance of fairies and little folk in Yorkshire, Catherine heads for the unvisited corners, and not for the obvious.

“The Cottingham flower fairies are of no interest to me at all”, she says, “they are so well-documented, the headline stories of their time and the hoax has spawned an industry of its own. I’d rather find out about neglected and obscure accounts and why our ancestors believed in, feared, or celebrated what they thought were very real influences in and to their lives”.

So, has Catherine stumbled on anything recently that she feels needs further exploration? It turns out that yes – and quite literally – she has. “I was over in Batley and Morley not so long ago, having a wander around, and I just chance to find the remarkable ruins of Howley Hall, which was once one of the greatest mansions in Yorkshire, a Harewood House of its day, and razed to the ground (well, almost) over three centuries ago.

"But why? The Saville family, who owned it, were once one of the most influential people in England, let alone the north. So why their fall from grace, why their spectacular slip into obscurity? I felt myself thinking ‘What was this all about then?’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Along the same lines, I’ve become interested in William Bradford. Who’s he? Well, every American schoolchild will know him as one of their Founding Fathers. But few in Yorkshire know that he came from Austerfield, just south of Doncaster. Imagine, someone from a rural community who was instrumental in developing a whole ‘new world’”.

She’s currently researching any number of topics – the part that the north of England played in the development of baseball as a national sport in the US is just one (“it had a phenomenal boom in Britain, pre-war”, she says.

Another is the early film industry, when Holmfirth was the film capital of Europe. And Catherine would like to see far more recognition given to three of her own female idols – Amy Johnson, the pioneering aviatrix, Flora Sands, who actually served int eh Serbian Army of WWI, and the missionary Gladys Aylward. This may all sound very profound, but Catherine has a twinkling sense of humour which flourishes alongside her academic studies.

She is nothing if not highly inquisitive. She asks, with a laugh, “Why is it that there are some people whom just research things until all the fun is drained from it. They’ll investigate if there was a Babylonian influence on the history of corn dollies, and produce a thesis on their being part of a pagan ritual, while I’ll just suggest that corn dollies were made because they were fun, and it was a nice token to give one to your would-be lover.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Or those jolly pigs carved into the pews of Beverley Minster – the ones playing the bagpipes? A threat of subversion against Christianity? Well, maybe. But far more likely because our medieval ancestors had a broad visual vocabulary! And, of course, it’s a jolly, pretty funky, and original design!”

Expect a lot more from Catherine Warr that if off-beat, unexpected, and delightfully entertaining.