Discover the beauty and secrets of Knaresborough

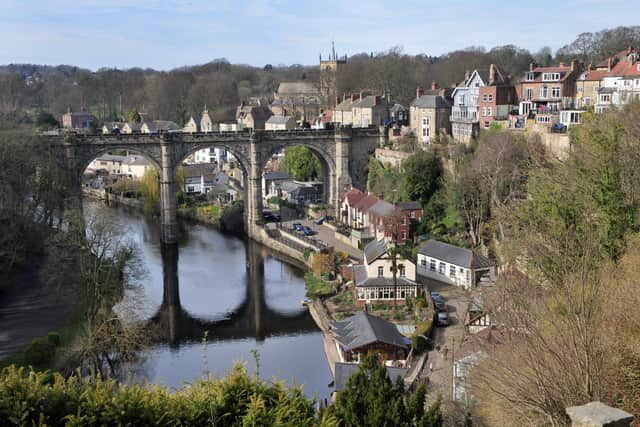

Knaresborough is a postcard-pretty market town. There’s a warren of medieval streets and stone staircases that weave their way up and down the hill. The town’s castle ruins perch on the cliffs above the River Nidd, with a stunning railway viaduct across the Nidd Gorge where daytrippers are normally able to hire rowing boats.

There are the many well-known attractions including what is believed to be the country’s oldest tourist attraction, Mother Shipton’s Cave and Petrifying Well, and the castle sitting above the river and gorge, in a commanding position with spectacular views.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut there is much more to this chocolate box North Yorkshire town than first meets the eye.

Much has been written about its history and legends, including five books by local historian Paul Chrystal. His most recent book, Secret Knaresborough, reveals little known facts about the town, often regarded as Harrogate’s little sister.

Chrystal, who once ran the Knaresborough Bookshop and has written many books about Yorkshire’s past, admits he is fascinated with the town and has spent years trying to unearth its secrets.

“I wouldn’t have written five books about it if it wasn’t a really interesting place,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile visitors to the town will know of Knaresborough Castle which was built in the 1100s on the cliff, not many will know of its importance in the history of Britain.

“Much has been written about the castle, but what people may not know is that the castle was built on the site of an earlier Anglo-Saxon fortified settlement or burg, strategically placed on a cliff towering over the River Nidd 120 feet below. The Angles’ name for this fort? Knarresburg.”

Chrystal says it then became a refuge for the assassins of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, in 1170 when it was owned by Hugh de Morville who was a good friend of King Henry II. “It was claimed that after the murder the owner’s dogs refused to eat the meat that was thrown to them from the table as it was against God – but that could easily be an urban myth.”

In 1210, Knaresborough was chosen by King John as the first place to give alms to the poor on Maundy Thursday.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile Knaresborough, its castle and its incumbents were favoured by the Crown and benefited from the wealth and kudos that brought with it, it eventually led to the castle’s demise. In 1644, Royalists loyal to King Charles I holed up in the castle when Cromwell’s forces advanced on it after the Battle of Marston Moor. “After a siege lasting several weeks, which saw dozens of men killed on each side, the garrison surrendered, after being promised their ‘life and liberty’,” says Chrystal.

It was largely destroyed in 1648 not as the result of the fighting, but because of an order from Parliament to dismantle all Royalist castles. Indeed, many town centre buildings are built of ‘castle stone’.

Visitors to Knaresborough can hardly fail to see the tourist attraction known as Mother Shipton’s Cave. An entire business has grown up around the Prophetess who was said to have foreseen events such as the end of the world and The Great Fire of London.

Mother Shipton was born Ursula Sontheil in 1488. Legend has it that she was born during a violent thunderstorm in a cave on the banks of the River Nidd in Knaresborough. Her mother, Agatha, was just 15 years old when she gave birth, and would not reveal who the father was.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith no family and no friends to support her, Agatha raised Ursula in the cave on her own for two years before the Abbot of Beverley took pity on them and a local family took Ursula in. Agatha was taken to a nunnery far away, where she died some years later. She never saw her daughter again.

Ursula grew up around Knaresborough. She was a strange child, both in looks and in nature. Her nose was large and crooked, her back bent and her legs twisted. She was taunted and teased by locals and so in time she learnt she was best off on her own, spending most of her days around the cave where she was born. There she studied the forest, the flowers and herbs and made remedies and potions with them, leading many to think that she was a witch.

When she was 24 she met Tobias Shipton, a carpenter from York. Tobias died a few years later and Ursula kept his name, Shipton. The Mother part followed later, when she was an old woman.

Much has been made of her so-called predictions, but most of them are legends or urban myths that have grown up over the years as well as her so-called ability to turn everyday objects into stone – more a phenomena of the sulphates in the water than magical forces.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe cave has become big business for Knaresborough tourism, with 65,000 visitors a year, and was once owned by the magician Paul Daniels.

If Mother Shipton is seen as Knaresborough’s most famous daughter, then Blind Jack must be its most unsung hero. “While he is celebrated locally, nationally people have never heard of him which is something of a travesty,” says Chrystal.

Blind Jack was the nickname of John Metcalf, born in 1717 in a cottage near the parish church. At the age of six he was afflicted by smallpox, which left him completely blind. “At 15, he was appointed fiddler at the Queen’s Head, in High Harrogate,” Chrystal writes in Secret Knaresborough. “Later, he earned money as a guide (especially at night-time), eloped with Dolly Benson, daughter of the landlord of the Royal Oak (later the Granby) and, in 1745, marched as a musician to Scotland, leading Capt Thornton’s ‘Yorkshire Blues’ to fight Bonnie Prince Charlie’s rebels.”

Today, he is best known for his work as a pioneer of road-building. He and his gang of workmen completed about 180 miles of road in Yorkshire, Lancashire and Derbyshire – including a bridge over the Starbeck on the road from Knaresborough to Harrogate. Today, a bronze statue of Jack, created by Barbara Asquith, sits on a seat in Knaresborough’s marketplace. “I think if he had done what he did for Yorkshire down south, he would be a national hero,” claims Chrystal.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe River Nidd runs through Knaresborough. Its name comes from a Celtic word meaning ‘bright’ or ‘shining. “It has always been essential to Knaresborough’s economy, as a means of transport, a source of fish, and a provider of power for water mills.”

In 1818, it supplied power for 48 mills in total – seven lead mills, one cotton mill, 18 flax mills and 22 corn mills. It has also provided a source of water and – until Victorian times – was used to dump sewage.

The current viaduct, which connects Knaresborough with Harrogate, was opened in 1851, but it is in fact the second viaduct. The first was supposed to have opened in 1848, but the first construction collapsed into the river very near to completion. The resultant noise of the falling masonry was said to have lasted for five minutes. Whilst there was no official inquiry, it is believed that the collapse of the viaduct was down to a combination of bad workmanship, poor materials and excess water in the swollen river below as a result of heavy rain over a period of two months.

But it is not just its history that makes Knaresborough an attraction. Wander through the streets and you may well end up doing a double take as you see everything from a giraffe to Guy Fawkes, who grew up outside Knaresborough in the village of Scotton. The Trompe L’Oeil paintings are in fact public works of art illustrating characters and scenes from the town’s history in the blank windows which are a feature of the Georgian buildings around Knaresborough.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe largest event is the annual Great Knaresborough Bed Race which was started in 1966 by the local Lions. A number of teams push their elaborately decorated beds along a demanding course around the town, including a challenging river crossing and the long climb up for a lap of the marketplace.

Sadly, this year’s event has been cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic, but it is sure to return as it’s woven into the town’s fabric and part of Knaresborough’s enduring allure.

paulchrystal.com

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.