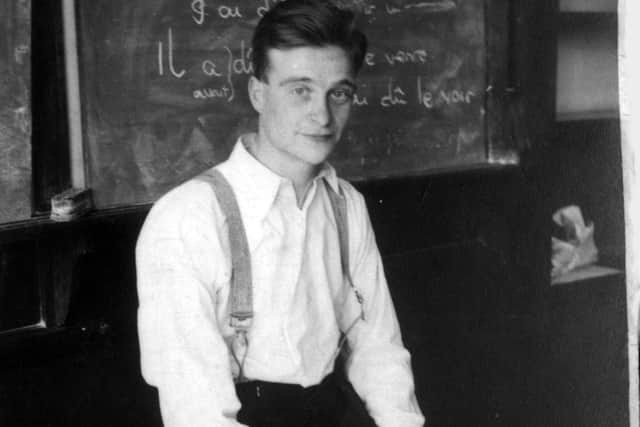

Double life of Bradford teacher who was a wartime spy

Harry Rée never betrayed the secrets of Churchill’s “underground army” of which he was, according to its official historian, one of its six best men. He said only that it had been a “glorious summer holiday”’ in which he had cycled around the continent and enjoyed the hospitality of the locals.

In fact, as his son eventually discovered, he had been part of the Army’s Special Operations Executive, a clandestine unit that waged a guerrilla war behind enemy lines.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet when his time supervising the blowing up of trains, bridges and factories was over, he returned to his other life in the classroom. And today, he is remembered at the exclusive Bradford Grammar School not as a war hero but as an inspirational educator.

The jigsaw of his life has been pieced together by his son, Jonathan Rée, a historian and philosopher born two years after Harry settled in Bradford.

“He was a schoolmaster all the way through. He said the war was a separate scene in his life that didn’t connect to anything before or after it,” he said.

His new book, A Schoolmaster’s War, reveals that despite having signed the Peace Pledge, his father had been parachuted into France in April 1943, after being trained in sabotage, silent killing and in passing himself off as a native. He devised a system for smuggling messages to London, advised on sabotage techniques and directed French Resistance operations against railways, canals, power stations and factories. He reportedly organised the destruction of a Peugeot factory and arranged the dropping of armaments and explosives by the RAF.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Harry may have started off as a pacifist, but he ended the war as a secret agent,” said his son, who began researching the book after an approach from a French soldier investigating the history of the resistance movement.

Yet upon his appointment to Bradford Grammar after the war, Mr Rée fell back into normality with remarkable ease.

“It would not have been uncommon for a teacher to have served in the war at this time, but perhaps what was extraordinary was the extent of his work in France,” said the school’s development director, Lindsey Davis, who has collected reminiscences from alumni.

Aware that he had been part of the French resistance but knowing few details, they speak of him as a “reticent” man whose “dress or values seemed at odds with the rather traditional staff attitudes we had got used to”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne former pupil remembered his “large, rather dilapidated stone built semi-detached house” on Bradford’s Toller Lane.

Another, recalling the almost prone position from which he taught, with his feet on his desk, said: “He readily disclosed his age – he was much younger that all the others who had weathered the war – and he was the first to treat us like contemporaries.”

The son of a chemist, Mr Rée was later the first professor of education at York University and a long-distance hiker who wrote a guidebook to Yorkshire’s Three Peaks.

His political beliefs turned him against fighting, said his son, “but he felt that if he went back to being a schoolmaster having copped out of the war, his pupils would disrespect him”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe added: “He was extraordinarily courageous but people expected him to tell stories of derring-do. The reality was more tragic.”

Mr Rée died in 1991, aged 76.

Editor’s note: first and foremost - and rarely have I written down these words with more sincerity - I hope this finds you well.

Almost certainly you are here because you value the quality and the integrity of the journalism produced by The Yorkshire Post’s journalists - almost all of which live alongside you in Yorkshire, spending the wages they earn with Yorkshire businesses - who last year took this title to the industry watchdog’s Most Trusted Newspaper in Britain accolade.

And that is why I must make an urgent request of you: as advertising revenue declines, your support becomes evermore crucial to the maintenance of the journalistic standards expected of The Yorkshire Post. If you can, safely, please buy a paper or take up a subscription. We want to continue to make you proud of Yorkshire’s National Newspaper but we are going to need your help.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPostal subscription copies can be ordered by calling 0330 4030066 or by emailing [email protected]. Vouchers, to be exchanged at retail sales outlets - our newsagents need you, too - can be subscribed to by contacting subscriptions on 0330 1235950 or by visiting www.localsubsplus.co.uk where you should select The Yorkshire Post from the list of titles available.

If you want to help right now, download our tablet app from the App / Play Stores. Every contribution you make helps to provide this county with the best regional journalism in the country.

Sincerely. Thank you.

James Mitchinson, Editor

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.