Maltby - the story of a mining town and a strange game called Beck Ball

In addition to the strong native South Yorkshire cadences, you would have heard a variety of Scots inflections, the Wesh lilt, and the mellifluous sound of Geordie voices. Not to mention those from Staffordshire, Ireland and elsewhere.

Why did they all congregate in this small patch of Yorkshire? The answer is simple. Maltby’s first coal mine opened in 1907, and workers (with their families) flocked from far and wide. The number of in-comers was so vast, that the mine-owners were required to build a new Model Village to house the men and their wives and children.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt became an estate of some 400 or so houses. There were also new churches and chapels, and alongside them, a number of working men’s clubs, including The Slute – which was local shorthand for the Miner’s Welfare Institute. There were clubs for every taste and religious inclination.

Sports clubs popped up, too. The first among these was the Miners’ Institute, which backed both the Maltby Main football and cricket sides, and the Roche Abbey Cricket Club, where a certain Fred Trueman first started getting noticed as a handy lad to have in your team – and as a formidable opponent if you were fated to play against him.

Until the coal industry opened the population floodgates, Maltby had been a quiet town that depended on agriculture, and which had, at the end of Victoria’s reign, a population of just 500. By the 1920s, and up until about 30 years ago, the figure stood at around 19,000, but since the closures, some ten thousand have moved elsewhere.

We know that among the first settlers here were the Vikings, because Maltby derives from a common Danish name, “Malti”. When our old chums the Domesday scribes turned up in the 11th century they noted the place as Maltebi – Malti’s village, or large dwelling place.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the years, there are also several other spellings, which include Malteby, Mauteby, Mahuteby and Mawtby.

When nearby Roche Abbey was founded in 1147 by a band of Cistercian monks, it was the people of Maltby who served as lay workers in the foundation’s fields, and whose skills built the abbey and its outbuildings, and whose labour in the adjoining pastures fed the monks. They also used the same water from the stream that flowed through both communities.

However, the partnership did not flow all one way, for the Maltby folk also worshiped at the abbey and took full advantage of the medicinal knowledge of their religious brothers. This harmonious and balanced combination of skills and requirements came skidding to an abrupt end when Henry VIII suppressed the monasteries. Roche’s doors were forced shut in June 1538, and the 14 monks and several dozen novices were told to move on.

This was a heavy blow to the community in that so much knowledge in one place was abruptly dispersed, though the locals also took advantage of the disruption by using the abbey’s timber and stones to incorporate in their own homes and farms. The amount of lead looted from the roof and windows of Roche was staggering. A contemporary writer called it all “nothing but pillage”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA few centuries on and the closure of Maltby Colliery in 2013 had a devastating impact, with over 500 jobs lost overnight. The company which owned the pit said that the site was “no longer viable on safety, geological and financial grounds”.

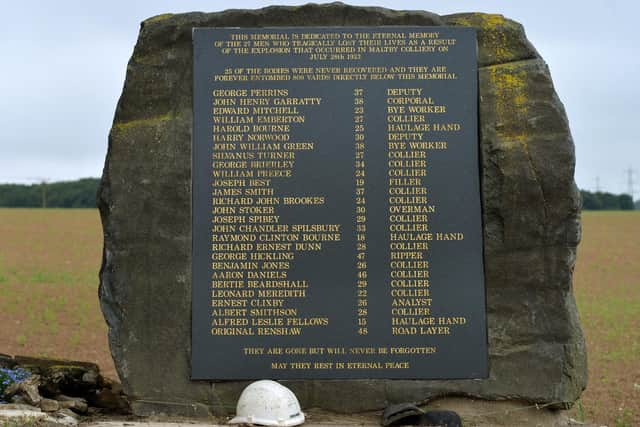

It was the end of over a century of hewing coal, and those years had not been without incident, for there is a fine granite and black marble memorial in Limekiln Lane to the 27 men who perished in the Maltby pit disaster in July 1923.

Tragically, only two of the bodies were identified after they had been recovered when a terrible explosion of ignited methane gas ripped through the shafts, which were later sealed off. It is still known as “Black Saturday”. Of the names recorded on the memorial the oldest was only 48, and the youngest was Alfred Leslie Fellows, a haulage hand aged just 15. The majority of his mates were in their twenties and thirties, and they left behind 22 widows, and 57 fatherless children.

As soon as the news of this tragedy reached the wider world a “Shilling Relief Fund” was immediately set up, where the people of South Yorkshire and North Derbyshire were asked – if they could afford it – to put “one silver shilling” (that’s 5p today) at local collecting points in communities as far apart as Barnsley, Doncaster and Chesterfield. It is recorded that, in Sheffield alone, some people donated as much as £5.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA staunch supporter of that fund-raising in the 1920s was the Earl of Scarbrough, and his grandson, the 13th Earl was at the unveiling of the memorial in 2015.

The title dates back to 1690, when an incredibly grateful William III was invited by seven of the most prominent noblemen of the day, to invade England, and depose his father-in-law, James II. In that septet was Richard Lumley, the 2nd Viscount Lumley. The Dutch William was so grateful to the viscount that he became the first Earl of Scarbrough. Lumley had earlier played a significant role in the suppression of the rebellion begun by the Duke of Monmouth, who was the eldest illegitimate son of Charles II.

The main seat of the present earl, and his forebears, is at nearby Sandbeck Park, an impressive Grade I listed Palladian mansion. The grounds were designed by the gardening superstar of his day, Lancelot “Capability” Brown. The park is one of the few in the country that also has a listing – Grade II. But they are not alone, for they are joined within the park walls by another 11 Grade II features, including a chapel, a pair of ha-has, an icehouse, some stables and a barn.

That rich mix of regional accents was further broadened during the Second World War when a munitions factory opened. Most of the workers were from North London and a housing estate had to be built for them, known as “little London”. By the time that ROF Maltby was decommissioned in 1957, they had made nearly 800,000 weapons.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMaltby has other quirky claims to fame. It can proudly claim to be the only place where the game of Beck Ball is played. All you really need to know is that this “sport”, revived a few years ago, involves four teams, two balls, and a dammed stream which runs across a central pitch.

In recent parish council notes, a writer records, glumly, that Maltby “has been home to no-one of any note, fame or notoriety”, adding that, in 2000, a time capsule was buried at the Village Hall.

Maltby, in many ways, is a template for Yorkshire. People here just get on with it. And when life delivers lemons, they make lemonade.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.