New light at end of navvies’ rail tunnel between the Dales

Up to 50 men lost their lives digging the passage under the village of Bramhope that allowed trains to run from the Wellington terminus in Leeds to Harrogate, Thirsk and onwards to Stockton.

On the 170th anniversary of its opening, the replica that stands four miles away as their memorial will be rededicated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHidden behind the parish church at Otley, the Navvies’ Monument is the only one of its kind. Beneath its Gothic, castle-like battlements, built to mimic the of the tunnel’s north entrance, are interred 23 men, aged from 20 to 48.

But researchers piecing together its history for an anniversary book and film, believe it tells only half the story.

“The actual number is far higher – 49 or even 50,” said Mark Currie, a filmmaker who has produced a 30-minute documentary, The Navvies Who Built The Bramhope Tunnel, as part of the commemoration.

“They didn’t all die in the tunnel itself, but certainly along that stretch of the line.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

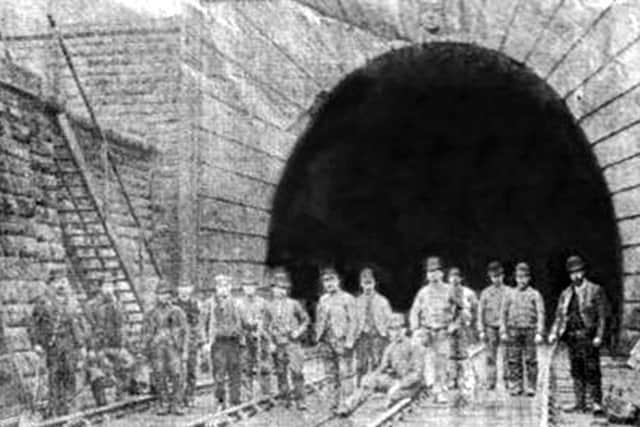

Hide AdThe construction of the tunnel, between 1845 and 1849, saw navvies encamped at Bramhope – today a desirable suburb of Leeds. They had been engaged to excavate a 2.1-mile tunnel that would link Horsforth to the south with the Arthington Viaduct, which would take the railway line over the River Wharfe to Harrogate and beyond.

It was one of the longest rail tunnels in the country and formed part of the ambitious Leeds and Thirsk Railway which would open a trade path between the burgeoning economies of Yorkshire and the north-east.

But it required a route to be cut through the ridge between Airedale and Wharfedale.

Workers by the thousand were enlisted – some from Otley but most from further afield – to realise the ambitious plans of the Edinburgh civil engineer, Thomas Grainger.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen they had finished, some of those who had survived lived for a while in the sandstone castle towers and turrets at the north entrance, which are now Grade II listed monuments.

Of those who did not live to see their work finished, only one was afforded his own grave.

James Myers, 22, who in an age before hard hats was hit on the head by a falling stone, was laid to rest in the Methodist Cemetery behind Yeadon town hall. Next to him is the body of his three-year-old daughter, who died three weeks later.

“You can only imagine what that must have been like for his wife,” said Mr Currie. “We also found a letter in the Northumbria archives from the widow of another man who died.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She wrote that the last time she had seen him, he’d made breakfast for her and their baby, then told her he had to leave for fresh work. He kissed them both and said goodbye.”

A similar community of navvy camps would spring up three decades later, further up the Dales, when the Ribblehead Viaduct was constructed on the line from Settle to Carlisle. But the monument at Otley, itself Grade II listed, is the only one dedicated to the transient community.

Its rededication will take place on July 13, followed by a screening of Mr Currie’s film. A 60-page book called What Lies Beneath, by historian Angela Leathley, will also be published.

Ray Georgeson, chairman of Otley Town Council, said he hoped the commemoration would “allow an important but perhaps little-known part of Britain’s history to live on.”