Romans, pottery, Henry Moore and Buffalo Bill - This is Castleford's story

So what, you might say. Well, perhaps this local saying doesn’t mean much today but it does offer a clue about the strategic importance of the West Yorkshire town. For not only is Castleford at the confluence of two of Yorkshire’s major rivers, it also marks a shallow point in the Aire, which made it a safe crossing point for Roman legions as they trudged across England nearly 2,000 years ago, and an ideal staging post between Doncaster and York.

The town’s rich Roman history – it has one of Europe’s biggest collections of artefacts – is well documented, but the Romans weren’t the first to settle here. Bronze Age examples of pottery and flint show that people lived in Castleford in prehistoric times, and during the Iron Age there were well-established farms here.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTony Wallis, vice chairman of the Castleford Heritage Trust and the town’s Civic Trust, says it wasn’t until many centuries later that the town made its name. “It was a very important industrial centre during the industrial revolution.

"That’s when we start to see the mining and the potteries and the textiles and the glassworks which turned Castleford from being little more than a village into a major town,” he says. “In the 19th century it grew rapidly and people came here from all over the country to find work.”

Writer Ian Clayton is a Featherstone man but has worked in nearby Castleford countless times down the years and knows the place well. “It has a proud history of artisan work. There were a lot of potters in Castleford and there was a whole area of the town known as ‘the Potteries’. There was a famous pottery maker there back in the early 19th century called David Dunderdale that made exquisite pottery – it was up there with the likes of Wedgwood.”

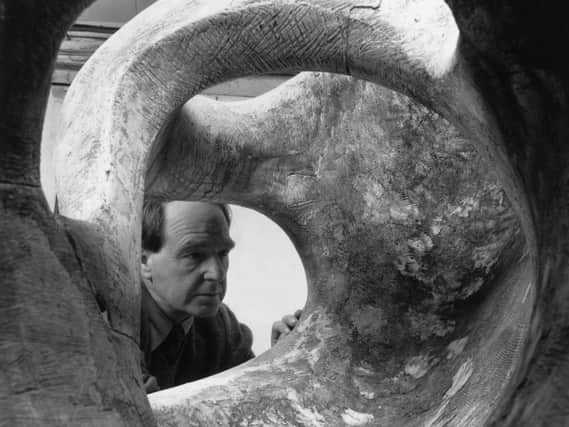

Some of the factories became known for decorating pottery, too. Pottery painting classes began in Castleford around 1920 and continued for more than 30 years, and Henry Moore, who grew up in the town, was among those that took part in evening classes run by his old art teacher, Alice Gostick.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMoore was brought up on Garden Street though the house he lived in was later demolished (reportedly so the bin lorry could get down the street). And while he left to forge his stellar career elsewhere, his fondness for his home town never left him.

“He came back to Castleford and made a film for TV,” says Clayton. “He walked around describing memories from his youth and you see him touching the red brick walls and saying how important they are because they hold the history of the town.”

If Moore is Castleford’s most famous son, then Buffalo Bill is surely the town’s most extraordinary visitor. He certainly made an impression when he arrived with his Wild West circus in 1904. “He came with his full regalia, there were trick cyclists, camel riders from Bedouin countries and Cossack horsemen. It was a massive show and it took two trains to bring all the equipment wherever they travelled to. When he came to Castleford he rode on a white horse from the station up to Lock Lane and set up near the River Aire,” says Clayton.

Buffalo Bill isn’t the only notable performer to have been to the town. The Theatre Royal, designed by the great Frank Matcham, played host to many showbiz stars in the first half of the 20th century. Among them was a young Stanley Jefferson, aka Stan Laurel, in what was believed to be one of his first professional performances, appearing way down the bill behind Wee Georgie Wood.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s where George Formby met his future wife (she was a clog dancer on the same bill as him) and it’s also where a famous catchphrase was born. During the 1950s many theatres were in decline following the arrival of TV and the huge popularity of cinema, and to make money they often resorted to putting on slightly seedy nude revues.

“They’d create a tableau, something like the decline and fall of the Roman empire and they’d have these girls barely dressed holding up mock Grecian urns,” says Clayton. “In those days, the Lord Chancellor allowed nudity in a theatre as long as the person didn’t move.

"And on one occasion a young comedian came in and left the backstage door open and the draft from Wilson Street blew in across the stage and one of the girls turned round and said ‘shut that door’. And when they went off the young comedian walked on and uttered the immortal words ‘shut that door’. It was Larry Grayson.”

Like many post-industrial towns in the North, Castleford has struggled over the past 50 years as the big traditional industries and mainstays of employment disappeared one by one.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, there is some cause for optimism more recently. The town’s close proximity to the motorway network has seen the growth of out-of-town warehouses which, while not replacing all the jobs that were lost, has at least brought a renewed focus. “There’s been a change from manufacturing to more service sector and distribution jobs,” says Wallis.

Locals still talk about their town as “classy Cas” – a reference to the club’s rugby league team which remains a genuine badge of pride. Then there’s the volunteer-run Queen’s Mill which sits on the banks of the Aire. Known locally as Allinson’s Mill, in its heyday it was thought to be the largest stone-grinding mill in the world.

In 2013, the Castleford Heritage Trust, with the help of an anonymous benefactor, bought the building which had closed its doors as a commercial enterprise three years earlier and was heading towards dereliction. The mill then became the new base for the trust and provided space for offices and a live music venue, as well as all manner of creative workshops.

It has brought this local landmark back to life and Wallis feels it typifies the attitude of locals which has never wavered despite all the hardships. “I think people from Castleford are fond of their town and there’s a real camaraderie here that’s left over from when the factories and mines were here. There’s still that community spirit.”

Support The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYour subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you'll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers.

So, please - if you can - pay for our work. Just £5 per month is the starting point. If you think that which we are trying to achieve is worth more, you can pay us what you think we are worth. By doing so, you will be investing in something that is becoming increasingly rare. Independent journalism that cares less about right and left and more about right and wrong. Journalism you can trust.

Thank you

James Mitchinson