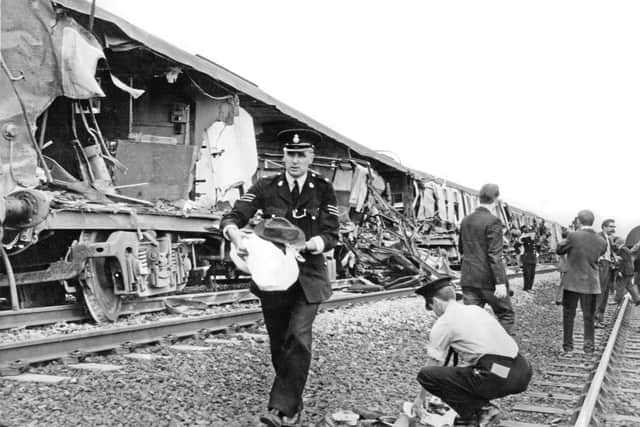

Flashback: Yorkshire rail crash that left seven dead

The latter was responsible for a serious collision of trains running on the East Coast Main Line just south of Thirsk on July 31 1967.

The 12pm King’s Cross to Edinburgh express passenger service, hauled by Diesel Prototype 2 (D.P.2), was derailed after striking a loaded cement wagon fouling the fast line.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese wagons were particularly noted for their propensity to develop problems with the suspension, which caused them to become unstable at speed, leading to a 45mph restriction on the cement trains.

However, the vigilance of railway staff could not prevent the accident and, sadly, seven people were killed, fifteen seriously hurt and thirty treated for minor injuries.

The cement train had started from Cliffe, Kent, at 2.40am and slowly travelled north towards Uddingston, Glasgow.

Along the way the wagons were checked at London’s Ferme Park marshalling yard, Peterborough, Doncaster and York and would have also been seen at Newcastle had the train arrived there. These inspections were quite thorough, lasting around 20 minutes, and three wagons had been detached owing to mechanical troubles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the last check at York no faults had been detected and the train proceeded at 14.52. By about 15.15 the twelfth wagon from the front came off the slow line, taking a number of wagons behind down an embankment. The driver of the locomotive stopped, running to the nearest signal where there was a phone to alert the signal box.

The guard at the rear of the train also followed safety procedures by attempting to place detonators on the track and planting red warning flags, but this was to be no use as the express was already approaching.

The passenger train was 600 yards from the crash site when driver J. Evans saw a cloud of dust obscuring the line ahead. This concerned him and he slowed down from 80 mph and the locomotive was travelling at nearer 50 when the derailment became obvious and emergency brakes applied.

This was not enough to make a significant difference to the speed and the locomotive ploughed into one of the rear cement wagons that had not been pulled down the embankment. The wagon and contents weighed about 35 tons and caused significant damage to the left-hand side of D.P.2 and the three carriages following. The next four coaches were also affected and left the line, but remained upright.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA labourer working in a field near the track witnessed the accident and phoned immediately for the emergency services, which were on the scene rapidly and removed the injured between 15.40 and 16.30.

The task of clearing the line was not completed until 23.30 on 1st August. Repair work to the track then took another day and normal running on all four lines did not resume until the evening of 2nd August.

In the thorough investigation that followed the twelfth wagon was found to have badly worn suspension, which allowed the axles to move from side to side. This became more pronounced and dangerous at speed and was a significant factor in the derailment.

There was a slight twist in the track and, while this would not normally have been a concern, the fault created a unique set of circumstances that allowed the wheels of the cement wagon to leave the line.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe accident report was damning towards the suspension. The average lifespan was only between 2,000 and 6,000 miles and the rapid wear was a direct result of cement dust getting into the components.

The maximum speed limit applied to the cement trains was also singled out as inadequate, because after tests were performed the movement of the axles reached a critical limit at speeds over 35 mph. The report therefore recommended that the this should become the restriction.

Any blame for the accident was removed from the men operating the two trains and they were singled out for praise in relation to their valiant attempts to stop the collision.

The report noted: ‘Their actions and those of the other railwaymen directly concerned in this unfortunate accident were worthy of the highest traditions of the railway service.’