1969: When the Beatles broke up and the party had to stop

The seminal 12 months of pop that saw the dissolution of the Beatles and the birth of the festival generation began 50 years ago, this week, with an uncomfortable fusion of two musical cultures.

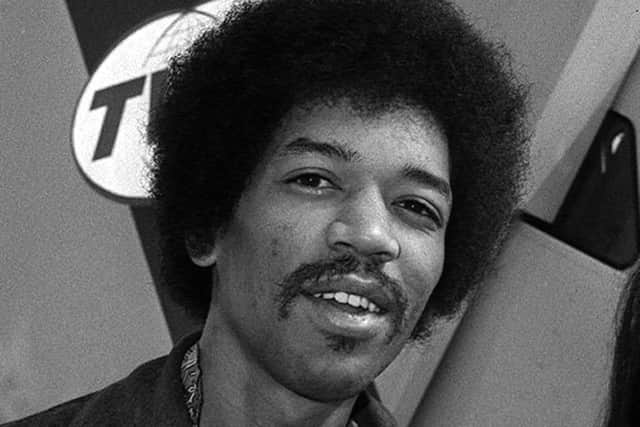

Shortly after New Year 1969, the guitarist Jimi Hendrix arrived at the BBC in London to perform on a light entertainment show with Lulu. It was a booking that would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Sixties had not yet drawn to a close but it was already obvious that they had turned everything upside-down.

“1969 was when something changed and something ended,” said Rupert Till, professor of music at Huddersfield University.

“There had been a real purple patch of incredible creativity, which was really exciting.

“But like any other generation, it got to the point where those people had kids or got jobs, and the rose-coloured spectacles came off.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor the most influential band of the decade, it had begun to unwind in January, when they performed for the last time, in front of film cameras but no audience, on the roof of Apple Records in London. The police broke up the concert. There was to be no encore.

On September 20, at a meeting between three of the Beatles – George Harrison was absent – and their business manager, John Lennon announced he was quitting. The following week, Abbey Road, the last album they recorded together, was released.

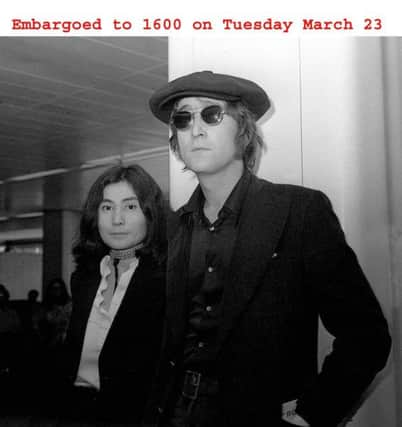

Six months earlier, Lennon had set out on a different journey, marrying the artist Yoko Ono, and staging a “bed-in” in Montreal, in the cause of peace.

In the seven years since their first single, the band had been at the vanguard of a musical and cultural revolution that bridged the years between rationing and conscription, and the permissive society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey had also changed their own industry profoundly, Prof Till said.

“The biggest difference was that they wrote their own music, and they were recognizably British. In the 1950s, there was no sense that your culture was really distinctively different to that of your parents,” he said.

“But the Beatles were different. We take it for granted nowadays that artists write their own songs, yet in their day it was really quite unusual.

“There had always been professional songwriters, and above them there were producers who chose a song and a singer to perform it. Musicians were just performers, not artists who controlled the whole thing.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the time Hendrix arrived to perform with Lulu, the world had turned. The usual twee duet on stools with the host, was out. “We’d like to stop playing this rubbish,” Hendrix said.

Eight months later, the 400,000 young people who made a pilgrimage to a farm in New York’s Catskill mountains for a four-day music festival betrayed a similar subversiveness.

“A lot of people thought they were isolated in rejecting the values of their parents – that it was maybe just them and a few of their friends” Prof Till said.

“But Woodstock proved that here was a large and significant cultural movement.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmerica’s continued involvement in Vietnam, and the threat of the draft that still hung over its teenagers, helped make the revolution turn – but in the end, Prof Till pointed out, reality kicked in and music discovered its influence was not infinite.

“Because the mood grew so quickly, it was also quickly shut down,” he said. “It couldn’t be allowed to just spiral upwards. It turned out you just can’t change the world.”

Tomorrow: Thatcher and the politics of change