50 years on - Shabby truth behind the Great Train myth

The Great Train Robbery took place 50 years ago today in the Buckinghamshire countryside where the Glasgow-Euston overnight mail train was stopped and relieved of millions of pounds worth of used banknotes.

It was ludicrously glamorised and its participants adulated as latter-day heroes who had carried out a Boy’s Own exploit of great derring-do.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it should have been called the Great Bungled Train Robbery. It was woefully planned and disastrously executed by a bunch of incompetent criminals. Most of them were behind bars within days of the heist and a lot of the £2.6m – a vast sum now, and an unimaginable amount half a century ago – was recovered.

Most people would assume that those planning such a massive crime would have prepared the ground in the most minute detail. In fact, the preparation was so slovenly, the robbers played straight into the hands of the police. It was a master-class on how not to carry out a robbery.

Right at the start, Detective Superintendent Malcolm Fewtrell, head of Buckinghamshire CID, said they were looking for a remote farmhouse, which had recently been the subject of a sale, and which was about 25 miles from the scene of the crime.

This is precisely what the robbers did. They reckoned a distance of 25 miles would give them the opportunity to make their getaway – neither too close nor too far – and to lie low at Leatherslade Farm (which they had recently bought) until the hue and cry had died down.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn fact had police heeded three earlier calls from a cowman, John Maris, who said there was “something funny going on” at Leatherslade Farm, the gang would have been rounded up even more quickly. As it happened, when the robbers, most of whom had form, realised the police were hot on their trail, they dispersed in chaos, leaving fingerprints all over the farm, on crockery, tomato sauce bottles and furniture. One of them later checked into a Bournemouth boarding house with a suitcase from which fivers were visible through the hinges.

The robbers did manage to find someone who was an expert on railway signals. He succeeded in changing the signal to red which stopped the train. But the train had to be moved forward a short distance from the signal to Bridego Bridge, where vans were waiting to be loaded with the loot. And the former engine driver they recruited for this part of the job had no knowledge of how to drive this type of engine. The gang had to force the real driver, the dazed Jack Mills, whom they had coshed, to drive the train to the bridge.

I was one of the first reporters on the scene. When I arrived I found a huddle of detectives examining the locomotive, which had been moved to nearby Cheddington railway station.

A few days after the robbery, but before Leatherslade Farm had been discovered, a Scotland Yard detective approached me and said he had a good story for me.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was that police were urging anybody who happened to notice that any male neighbours had mysteriously disappeared should alert their local station. The story went national.

Later that day, a police officer arrived at my London home and asked my wife where her husband was. Without a thought, she said: “He’s on the Great Train Robbery”. The officer almost fell back on his heels, thinking he had solved the crime of the century until he was apprised of my role.

One of my neighbours had “shopped” me as a result of my own story.

After the discovery of the farm, members of the gang – including those involved in the purchase of the property and other “backroom boys” – were picked up one by one. About a year later, I found myself in the witness box at the trial in Aylesbury. Summoned by the defence, I was questioned over my shorthand note of disputed evidence relating to Brian Field, who was involved in the purchase of Leatherslade Farm. My evidence plainly did not do much good – Field got 30 years, although it was reduced on appeal.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

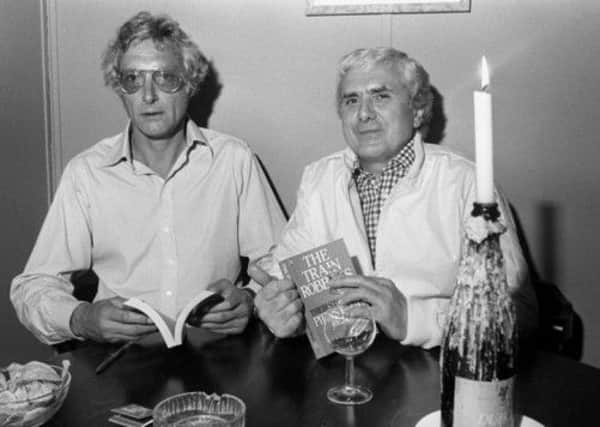

Hide AdMany of the robbers are now dead, although the “celebrated” Ronnie Biggs who escaped from jail and spent years as a tourist attraction in Brazil, is back in Britain. Bruce Reynolds, who was “credited” (probably wrongly) with being the mastermind of the robbery, died recently.

Fewtrell told me shortly before he died a few years ago that the real masterminds had never been named. He knew who they were, but said the police never had enough evidence to prosecute them.

And so Fewtrell took those names, which I suspect we will never know, to his grave.