A true force of nature

In 1902 the Caribbean islanders of Martinique were shook from their usually quiet way of life by what would later be described as the worst volcanic eruption of the 20th-century. At the height of the disaster, which destroyed an entire town, rivers were turned into raging floods of boiling water, stones showered down from the sky and when clouds of suffocating vapours from the Mont Pelée crater swept across the island it only added to an already grim death toll.

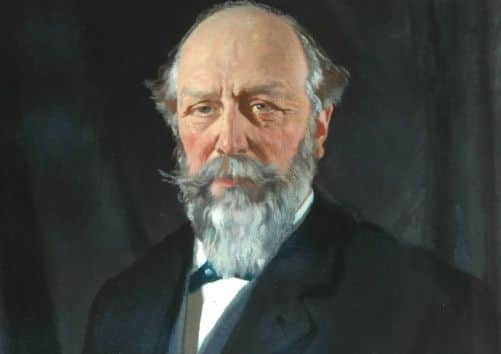

One of the first men on the devastating scene was a York eye-surgeon called Tempest Anderson. While his career might have been medicine, his other passion was geology and by the turn of the 1900s he had already earned a pretty formidable reputation as one of the world’s leading vulcanologists.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the time Mont Pelée showed the true force of nature, Tempest was in his early 50s and had already notched up expeditions to Vesuvius and Etna in Italy and had explored many of the volcanoes of note in Canada, South Africa and Iceland. Rumour had it, that at the end of his bed in the house he owned in Stonegate there were always two bags neatly packed – one for hot climates; the other for cold. As soon as news came of another eruption, Tempest was off. “Among his many other claims to fame, he also had the very first telephone in York,” says Emma Williams, assistant curator of science and archaeology learning at the Yorkshire Museum which is about to open a new display dedicated to the city’s famous son. “It meant that he was among the very first people to hear about a new eruption and as he wanted to study the science of volcanoes it was important to be there as soon after an eruption as possible.

“From what we know, he seemed to be pretty fearless. You have to remember that this was an age when most people spent the majority of their lives in a few square miles. Travelling abroad was fraught with difficulties, yet at a moment’s notice Tempest Anderson would leave behind his home comforts without a second thought.

“It was incredible really the places he got to – most of his adventures took place off the beaten track and in often inhospitable environments. Even today once you’re out of Reykjavik, travelling around Iceland is not easy, so God only knows was it was like in the late 19th and early 20th-century. However, Anderson had that adventurous spirit which just seemed to make the impossible possible.”

On his West Indies trip, Anderson was accompanied by his friend, the Scottish geologist Dr John Flett and when the pair had completed their tour of Martinique, they sailed over to the neighbouring island of St Vincent where the La Soufrière volcano had erupted with equal force just a few weeks before the Mont Pelée disaster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs well as carrying out a number of geological experiments, Anderson was equally interested in gathering eyewitness reports. These first hand testimonies, which were weaved into his reports, helped to explain why the islanders had felt the full force of the eruption on St Vincent and not tried to escape.

“The eruption though sudden in its outburst and disastrous in its effects, was far from unexpected,” wrote Anderson. “In the north of St Vincent there were two settlements of the aboriginal Caribs and these had been so startled by the frequent violent earthquakes that in February last year they were considering the advisability of deserting the district.”

However, most decided to remain and when on the morning of the disaster one side of the volcano was wrapped in cloud, it prevented those who lived on land at its base from seeing the bursts of steam, normally a precursor to a full eruption.

Unaware they were in imminent danger, they continued to work in the sugar plantations and even when warning telegrams were sent to nearby Georgetown it caused little more than a ripple of anxiety. These were people who were used to living in the shadow of uncertainty and had become accustomed to La Soufrière’s occasional rumblings. By the time they realised the danger, streams of molten lava had already cut off their escape routes. For most the only option was to hunker down and hope for the best.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of those who survived told Anderson of the “huge reddish and purplish curtain” that had descended across one part of the island and others bore the scars left by the hot sand which had rained down from a dense black cloud.

“The exact number [who died] will never be known,” he concluded. “As many were entombed in the ashes were they fell.”

What he and Dr Flett observed in the Caribbean would change scientific theory forever.

“Basically he identified that a hot blast travels in front of the main eruption, knocking down trees and anything else in its way,” says Stuart Ogilvy, assistant curator natural science at the Yorkshire Museum.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It’s what is now called a ground surge. Tempest had spent a lot of time in the Alps and he realised that a volcano erupts in much the same way as an avalanche happens. The only difference is that with an avalanche you get a blast of cold air just before the deluge. He wrote a number of papers on the science of volcanoes and even all these years on they are still highly regarded.”

Alongside his inquisitive mind, Anderson was also blessed with the spirit of invention. In his York house a metal tube – a primitive form of intercom – ran from the front door to his bedroom so he could be called on at any time of the night to attend an medical emergency and it was through his work in ophthalmics that he learnt how to make his own lenses.

At first these were purely for medical use, but it wasn’t long before Anderson was also making his own cameras, which would allow him to compile an impressive photographic record of his travels.

“He didn’t just take pictures of the volcanoes, he took his camera everywhere and his images have provided a really detailed record of foreign cultures, buildings and transport. It’s a fantastic snapshot of a particular period of time,” says Stuart, who is over halfway through scanning 5,000 negatives of 3,500 different images. “He didn’t travel light, these lenses were incredibly heavy, but he took them everywhere he went – he even invented a panoramic camera with a revolving lens, which was way ahead of its time”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnderson never married, but his photographic archive also shows that he was never short of female company on his adventures.

“There are some incredible pictures of women in full Victorian dress and parasols stood at the base of these volcanoes,” says Stuart. “Given that they were often accompanying him to largely unknown territories where luxury was likely to be very limited, he clearly had powers of persuasion.

“The impression you get is that he was one of life’s genuinely good blokes. He was very highly regarded and well-liked, and exactly the kind of man you’d like to have as a travelling companion.”

One of the leading lights of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, when not chasing volcanic eruptions, Anderson was busy adding other strings to his bow. He was Sheriff of York in 1894, a long-serving member of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society and, while other Victorian explorers were busy hunting their way around Africa, he we also an enthusiastic environmental campaigner.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The philosophy of Victorian age was if it moves shoot it – conservation wasn’t really an issue,” adds Stuart.

“However Anderson felt keenly that man had to limit its impact on the environment and back home in York he was also a vocal support of the need for green spaces.”

Anderson died of “heat apoplexy” in 1913 while travelling back from the Philippines. He was 67 years old and while he was buried at Suez, a lasting reminder of his contribution to the world of science and medicine had already opened in York. Tempest Anderson Hall, an extension to the Yorkshire Museum, had been completed the previous year and true to form for a man who had spent his life pushing boundaries, the building had its own claim to fame – it was one of the first in the world to be made of concrete.

“Tempest Anderson fitted more into one year than most of us could ever hope to achieve in a lifetime,” says Emma. “His was a life that really deserves to be celebrated.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Tempest Anderson exhibition opens at Yorkshire Museum on July 20 and will run throughout the summer.

Piecing together eyewitness accounts

From Tempest Anderson’s correspondence from St Vincent, published in The Times in 1902.

“Then came the climax of the eruption, and those who were in the open air saw a dense black cloud rolling with a terrific velocity down the mountain. They took refuge in their houses and in the plantation works, where they crowded together in such numbers that in on small room 87 were killed. The cloud was seen to roll down upon the sea, and was described to us as flashing with lightning, especially when it touched the water. All said that it was intensely hot, smelt strongly of sulphur and was suffocating....The roaring of the mountain was terrible – a long, drawn out, continuous sound resembling the roar of a gigantic animal in great pain.”