After 60 years, CND is back where it started... in Bradford

An exhibition in the city centre marked the anniversary of CND, while across town, one of its most famous sons recalled with “no regret” the time he spent in Wormwood Scrubs defending the cause.

“It must have done some good,” said Michael Randle, now 84. “We still haven’t had a nuclear war.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was formally convened in February 1958, following the publication in the New Statesman of an article by Bradford’s most famous man of letters.

JB Priestley’s radio broadcasts during the war had made him a symbol of national resistance to Nazism, and now he called on the nation to set an example to the world once more by throwing away its nuclear bombs.

“As the game gets faster, the competition keener, the unthinkable will turn into the inevitable, the weapons will take command, and the deterrents will not deter,” Priestley wrote.

Mr Randle, then a firebrand who had conscientiously refused to do his National Service earlier in the 1950s, was among those moved to action.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe joined the committee that would organise the first march that Easter on the government’s Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston in Berkshire, and in a career of what he calls “direct action”, endured an 18-month sentence, along with five others, for organising a non-violent occupation of a US air base in Essex.

He had already gained experience of doing time – an earlier demonstration in Norfolk had seen him sent to an open prison for a month, alongside the philosopher Bertrand Russell and the writer Arnold Wesker.

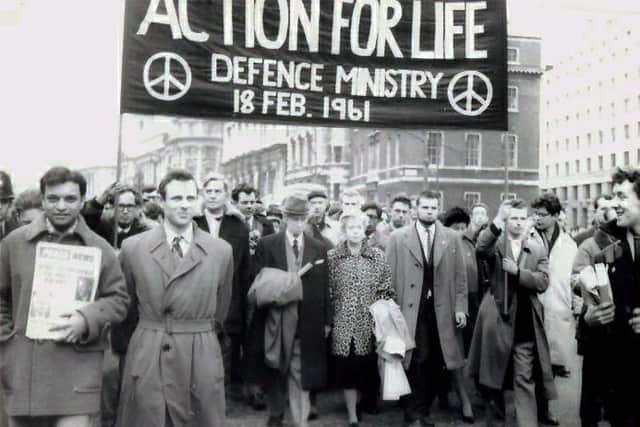

A photograph from the period shows a trenchcoated Mr Randle side-by-side with Russell and flanked by marchers, en route to court.

In Bradford, which has been his home for the past 50 years, and where he has lectured on peace studies, he said he regretted none of it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We still haven’t got rid of the bomb. But the United Nations did pass a resolution just last year declaring nuclear weapons illegal,” he said.

“Of course, it wasn’t signed up to by the nuclear states – Britain, France, the US, Russia – or any of your unofficial nuclear states like Israel. So it’s still a work in progress.

“But I think the extent of the opposition to nuclear weapons has helped to keep us safer. In a different atmosphere, it’s possible that we would have become involved in nuclear warfare.

“We haven’t got the nuclear disarmament the movement wanted – but we are still here and we have avoided a conflict.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe exhibition which opened last night at Bradford’s Peace Museum chronicles CND’s history through banners, badges and other artefacts from its collection, spanning the six decades.

Inspired by Priestley’s call to end arms, more than 5,000 people attended its first rally, and it grew into the biggest single-issue campaign organisation in Europe.

Paul Rogers, emeritus professor of peace studies at Bradford University, said the movement remained a relevant force. “If you take Trump and Kim Jong-un, it’s a fairly good argument for asking why we didn’t do something at the end of the Cold War to get rid of the things,” he said.

“It has been argued that in reality CND has won, because people think nuclear weapons are bad but that we can’t do without them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It could have gone the other way – it could have been a routine part of everything.

“Just raising the issue so forcefully at the time made people confront what was a long-term danger.”

CND has seen its membership swell since Jeremy Corbyn and Donald Trump put the issue back on the agenda.

“People are now worried that we’re returning to the era of being on a bit of a nuclear precipice,” said Prof Rogers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said the influence of the movement could be measured by the fact that of 195 member states of the UN, only eight had nuclear weapons.

“It’s eight and a half, if you count North Korea as a half,” Prof Rogers said. “But we haven’t had the proliferation that people feared.

“We’re away from the terrible period of the Cold War, when there was a tiny risk of all-out catastrophe – but people are now worried about the spread and the risk of smaller nuclear wars.

“So I don’t think we’re out of the woods on this one yet.”