The continuing battle to make hate crime in Britain a thing of the past

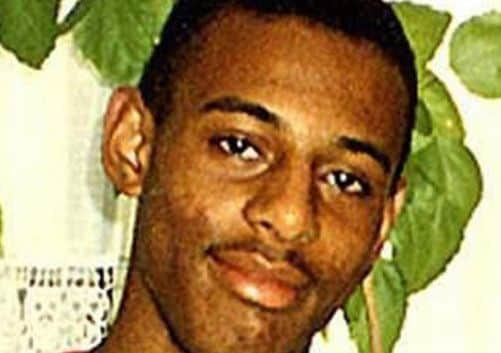

IT’S almost 20 years since Stephen Lawrence was murdered while waiting for a bus in south east London.

He was targeted and killed because of the colour of his skin, but his tragic death and the subsequent Macpherson report had a profound affect on the nation and attitudes towards hate crimes and racism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe latest Home Office figures show there were 43,748 hate crimes recorded by police in the UK in 2011-12, down on the previous 12 months. But according to British Crime Survey statistics it’s estimated that about 80 per cent of incidents may never get recorded, which means the figure could be as high as 260,000.

Andrew Bolland, partnership and contracts manager with Stop Hate UK, believes this is “nearer to the reality” of the number of hate crimes taking place in Britain each year.

Stop Hate UK is an independent organisation, based in Leeds, that supports hate crime victims and now covers a large swathe of the country. “If you go back 20 years to the period after Stephen Lawrence’s murder the focus was predominantly around race, but I think now we’re in a position where this has been extended to cover all forms of hate crime,” Bolland says.

Last year Stop Hate UK was contacted 3,150 times up from 1,446 in 2008-09. But Una Morris, project manager at Stop Hate UK, says an increase in the number of reported incidents doesn’t mean the problem is getting worse. “It could be because we are covering more areas, or it could be that more people know about us, or it could mean hate crime has gone up it’s difficult to say.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the biggest problems is we don’t know how many hate crimes go unrecorded. “There are people who are experiencing hate crime who are not telling anyone about it, they’re not telling us, they’re not telling the police and they’re not telling their friends or family members,” says Morris.

“So what we try and do is reach some of those people who wouldn’t talk to the police or their local council, but might come to us because we’re an independent organisation that can offer them support.”

According to official figures race is statistically the most reported hate crime, although last year Stop Hate UK recorded more disability hate crimes than race hate crimes. But what kind of incidents are we talking about? “The type of thing people will mostly hear about are the more serious violent incidents, murders and GBH offences. What people don’t hear about is the type of incident that typically gets reported to us which are lower level incidents of verbal abuse and ongoing harassment from neighbours,” says Morris.

These lower level incidents often aren’t deemed criminal but can still have tragic consequences, as happened with Fiona Pilkington and her daughter Francesca Hardwick. Pilkington killed herself and her disabled daughter in 2007 following years of abuse and harassment by a gang in Leicestershire.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis shocking case raised the profile of hate crimes, but as Bolland points out the effect on victims is often greater than for the victims of other crimes that aren’t motivated by hatred.

“More than 40 per cent of hate crime victims are fearful of repeat attacks compared to around 13 per cent for non hate crimes.

“If someone is the victim of a crime that’s not hate motivated then six months down the line they can rationalise that it’s just a random incident and they’re unlikely to be the victim of the same incident again. But if you’re targeted because of your sexuality, or race, then your perception is that you will be a victim of this again because it’s an attack on your personal identity, it’s not something people can walk away from.”

Morris says it can force people to change their normal everyday routines. “A lot of learning disabled people don’t want to go on public transport around the times that schools start or finish because they see that as the time they’re most likely to be targeted. So they will arrange their lives around avoiding particular situations where they think they might be targeted.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis shows that children, not just adults, can be the perpetrators. “There isn’t a stereotypical person who commits these hate crimes just as it’s not a stereotypical person who is the victim of a hate crime.”

It’s not just individuals who suffer either. “If someone from a certain race or culture is targeted then people from that community may worry that they could be the next victim so it has a much wider impact,” says Bolland.

The murder of Stephen Lawrence and the subsequent Macpherson report enshrined rights for victims of crime and extended the number of offences classified as hate motivated. But are we, as a society, more tolerant today? “You can take an area like Chapeltown or Harehills that have lots of different communities, which you might think would be a hotspot for crimes based on race. But when you talk to people from those areas the support structures are often in place and the diversity has been there a long time so people understand it.”

However, even where there is a higher number of reported hate crimes, it isn’t necessarily a sign of a more large scale problem. “It can be worrying if you see a big spike in incidents but it can also be a positive because people feel they are able to come forward,” explains Morris.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There won’t be anywhere that has no hate crimes, so just because somewhere has no reported cases that doesn’t mean it’s a good thing. We actually want to see more hate crimes in terms of statistics because that means more people are talking about what’s happening to them.”

In York this week, the city’s council cabinet ratified a new hate crime strategy aimed at preventing mounting tensions in the city, amid concerns that many victims are suffering in silence. York’s population has more than doubled in the past decade and senior police officers have admitted as many as two-thirds of offences are going unreported, prompting fears that a relatively low number of documented offences in the city is masking a far wider problem.

“There has always been a perception that York is a white, middle-class city, but things are changing significantly,” says Councillor Dafydd Williams, York Council’s cabinet member for crime and stronger communities.

“We are aware that we have to act now to ensure we have the support available to anyone who is the victim of hate crimes. The biggest problems are that people do not know where to go to report a crime, and are also worried that they will not be taken seriously. The actual number of reported offences may be relatively small, but anecdotally the issue is far wider.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhich is why the council is introducing a wide-ranging education programme aimed at pupils at the city’s schools as well as convicted offenders, to prevent the problem of hate crimes escalating.

Rose Simkins, Stop Hate UK’s chief executive, believes we have woken up to the importance of tackling hate crimes, but says there is still a long way to go. “We actually know very little about reported hate crime even though we have official figures, because we think they’re grossly under-estimated,” she says.

“We’ve heard stories about people who are trans who say they face half a dozen incidents every day. If you’re experiencing that many incidents then if you reported each one you would spend your whole life reporting them.”

But she says it’s important that people are encouraged to come forward and speak up about what is happening. “If we ignore what’s happening to an individual then we’re damaging that person and we can’t underestimate the damage that an attack on personal identity can do.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“You never escape who you are so if you don’t talk about it then you’re allowing yourself to be ignored and we should never be ignored.”

The Stop Hate UK 24-hour helpline number is 0800 138 1625.

Tackling hate crime in the UK

* A hate crime is defined as any offence committed against a person or property that is motivated by hostility towards someone based on their disability, race, religion, gender identity or sexual orientation.

* The latest Home Office figures show there were 43,748 hate crimes recorded by police in the UK in 2011/12.

* The Stope Hate Line was contacted more than 3,100 times in 2011/12, up 20 per cent on the previous year.

* Disability and race were the two most reported hate crimes during this 12 month period.