First World War hero and the ‘original’ great escape

WHEN Bertie Ratcliffe finally reached London he sent a telegram to his relatives in Yorkshire. It read simply: “Glad to tell you I have escaped ... staying with Teddie + Bert.”

It’s a brief, almost prosaic, sentence and one that belies a quite remarkable story. For in reaching English soil in 1917, Captain Bertram ‘Bertie’ Ratcliffe became the first British officer to escape from a prisoner of war camp and successfully make their way home during the Great War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had spent two-and-a-half years in captivity and his safe return gave hope to all other families whose husbands and sons had fallen into German hands during this unforgiving war.

Born in 1893, Ratcliffe was a nephew of the Leeds industrialist and philanthropist Lord Brotherton. He was educated at Harrow and Sandhurst and was commissioned into the West Yorkshire Regiment in 1913.

By September the following year he was in France where he was injured and left for dead at the Chemin des Dames during the First Battle of the Aisne.

He was later found by some German soldiers and sent behind the lines to a PoW camp – which involved him marching for three days with a bullet in his lungs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRatcliffe was imprisoned in Ingolstadt Castle, where doctors operated on him and helped nurse him back to health - one of the reasons why he had a fondness for Germans despite fighting them in two world wars.

He was the only British officer in the camp which included 200 French officers and despite his protestations his captors believed that he, too, was French.

While in prison he made several failed attempts to escape aided by friends and relatives back home.

Richard High, a senior librarian in the special collections department at the University of Leeds, takes up the story.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

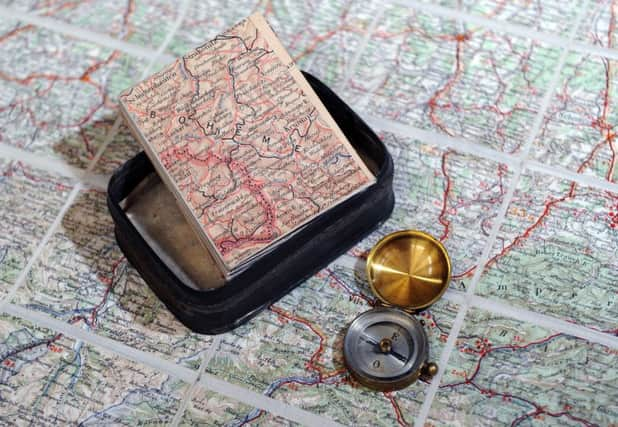

Hide Ad“A friend of his purchased a couple of maps of Germany and Bavaria in London with the intention of sending them out to Bertie in his prison camp. His plan was to solder the maps inside a sardine tin and send it as a food parcel. However, the person he asked to solder the tin got suspicious about this and dobbed him in to the police.”

But where his friend failed, Ratcliffe’s mother succeeded. “He had already drawn his own sketch map in the camp and his mother managed to smuggle a compass inside a tin of Harrogate toffee which he used to help him escape. He managed to reach the Dutch border, jumped on a train and finally got back to England a short time later.”

Several of these artefacts – including the maps that he never received and the compass that his mother secretly sent him – are now housed at the university’s Liddle Collection.

Ratcliffe’s escape offered some much-needed respite from the daily diet of death from the trenches and he was given a hero’s welcome on his return home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdClive Wigram, the king’s assistant private secretary, wrote a letter congratulating him on his escape, and added: “Should you happen to be in London at any time would you be so kind as to let me know, as His Majesty would like to see you and hear from your own mouth all about your experiences.”

Not only was he invited to have lunch with King George V at Windsor Castle he was also awarded the Military Cross.

But rather than sitting back and enjoying his newfound celebrity status he travelled to Palestine where he helped Britain’s war effort in the Middle East.

Perhaps wisely, given the likely reaction if he had subsequently been killed, he was kept out of the line of fire and instead was given a staff job working for General Allenby, who led the British Empire’s Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) during the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was in Jerusalem with Allenby when they walked on foot through the Jaffa gate, the first time the Holy City had been in Christian hands for around 600 years.

In a brutal conflict that claimed so many lives and caused such misery, Bertie Ratcliffe’s story is one that had a positive ending.

“It’s a tale of glamour and daring-do,” says Richard. “He was an exception and he was one of the first people who actually managed to make it back. It was quite a feat because he had to travel through Germany and get across Europe by which time there would have been a mobilised search for him.”

He points out, too, that people like Ratcliffe weren’t just heroes at the time, they also inspired later PoWs captured during the Second World War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The exploits of these people had quite a legacy. If you look at what Pat Reid talked about when he was writing about his escape from Colditz, he says in his book that the people who escaped during the First World War were an inspiration to him and others who escaped, whose stories we now know about from books and films.”

This wasn’t the end of Ratcliffe’s military career. When war broke out again just over 20 years later he returned to the army and served as a staff captain in the British Military Mission to the French Army, remaining in the post until 1945 when he finally left the army for good.

He went on to live an eventful life. He wrote also several books including a novel, Idle Warriors (1935), partly based on his own wartime experiences, as well as an account of Napoleon’s early life.

Ratcliffe was married three times and when he died in 1992, at the grand old age of 98, he was described by his family as a “Soldier, Writer, Poet, Lover” – not a bad epitaph to have.