First World War: the story of the pilot and his unusual mascot

AT one point during the First World War the average life expectancy of an Allied pilot was just 11 days.

It was a perilous existence and many didn’t even make it past their initial training such was the danger inherent in this new, untested, technology.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

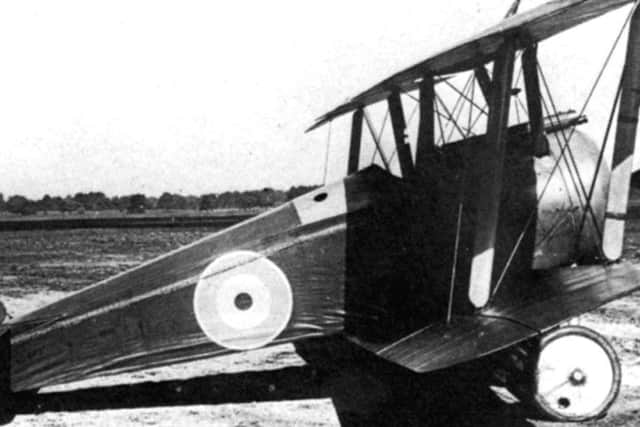

Hide AdPilots flew in open cockpits reaching heights of up to 20,000 feet and in the early part of the war some of the wooden-framed aircraft were so flimsy they could even be blown backwards in a strong wind.

It’s perhaps little wonder then that many of the young men who flew in these contraptions embraced anything which they believed might help them cheat the grim reaper.

Soldiers were known to surreptitiously keep a Bible hidden in their tunics and some pilots did the same, stowing one away in their cockpit.

Aviators also wore mis-matching socks and shoes during flying missions and many pilots refused to be photographed just before they took off for fear it would jinx them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOthers turned to macabre humour painting skeletons on the side of their aircraft, as much as a reminder of their own mortality as to scare the enemy.

It’s perhaps easy for us to dismiss these personal quirks and habits as superstitious nonsense, but when faced with death on a daily basis logic goes out of the window.

However, while folklore tales exist about some of the more unusual mascots that were adopted by First World War pilots, few still exist. Although one that does is housed here in Yorkshire.

Major Maurice Leblanc-Smith was a pilot with the Royal Flying Corps who fought in France and Belgium. He survived the war and a number of his wartime mementoes, including his logbook and a Distinguished Flying Cross certificate from Field-Marshall Haig, are now housed in the Liddle Collection at the University of Leeds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmong this memorabilia is a knitted toy dog called “Adolphus”, which was believed to have been given to him by a French girl and became his mascot on his flying missions during the war.

Mascots like this are very rare as many were lost, along with the pilots they flew with, which is why it is such an intriguing wartime artefact.

Special Collections Team Librarian, Richard High, says although details about Adolphus, such as where the name comes from, are scant, there is enough information to piece the story together.

“We know the dog was given to him by a French girl, but we’re not sure if this was a child or a girlfriend,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was Leblanc-Smith who put the colours around the dog which have now faded to an air force blue and we know this was his personal mascot and that it accompanied him in the cockpit.”

It’s not known exactly when Adolphus came into Leblanc-Smith’s possession but it became an intrinsic part of his flying ritual. “Mascots, superstitions, favours and adorning the mess with bits of aircraft and souvenirs was all part of this tradition,” explains High. “It ties in with the chivalrous approach to warfare, certainly in the earlier part of the First World War when pilots saw themselves as the knights of the air.”

Leblanc-Smith’s own story is an interesting one. Born in Surrey in 1896 to French and English parents, he trained as a pilot and joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in July 1915.

He arrived in northern France at the tail end of that year and over the next three years he became an experienced pilot who flew in several different aircraft including the famous Sopwith Camel.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThroughout the war he kept a log book detailing each of his flights, recording the time, date, wind speed as well as the nature of the mission and, in some instances, the skirmishes that took place.

In 1982, he was interviewed by Peter Liddle, who established the Liddle Collection, about his wartime experiences, in which he talked about the occasion he shot down three enemy planes in a single day.

“I was out on patrol in the morning and I shot down an Albatross [German military aircraft] scout. The next one was in the afternoon… I forget whether it was the first or the second aircraft that went down in flames. I was always rather sad about that in the end.

“I only hope the pilot was killed outright at the start because it’s a ghastly thing. There were no parachutes or anything of that sort.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the time the war ended in November 1918, Leblanc-Smith had risen to the rank of captain, shot down more than half a dozen enemy planes and been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC).

His citation described him as a “very efficient officer and successful patrol leader”, adding: “On a recent occasion he attacked five enemy aeroplanes, destroying one and driving down another.”

Leblanc-Smith witnessed aviation go from little more than a sideshow involving rickety aircraft, with pilots taking potshots at one another with pistols and shotguns, to it being a crucial component of modern warfare.

Those pilots who lived to tell the tale fervently believed that it was their mascots who helped keep them safe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRichard High points out that the very fact Leblanc-Smith kept Adolphus with the rest of his wartime memorabilia is proof of just how much he valued his lucky talisman.

“He kept Adolphus along with his log books and the certificate where he’s mentioned in dispatches and that shows just how important he was to him, in the same way that mascots and lucky charms were to so many pilots during the war.”