Grand plan to restore a rugged jewel of countryside back to peak condition

FOR many people, the English countryside will forever be synonymous with those stirring words from William Blake’s poem, Jerusalem.

The fact that we can still enjoy the same undulating hills and lush rolling fields that once inspired him not only help bind us to the past, they remind us that at its best ours remains a green and pleasant land.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe are, as a nation, passionate about our countryside and parks, they are our communal gardens, our back yards. And here in the Broad Acres we’re fortunate to have such iconic landscapes as the Yorkshire Dales, the North York Moors and the rugged terrain of the Peak District right on our doorstep.

It was the wild, rugged beauty of the latter that sparked the right-to-roam movement, when walkers tackled Kinder Scout in the mass trespass of 1932. Now the Peak District has become the focus of the National Trust’s “biggest and most ambitious” landscape nature conservation scheme.

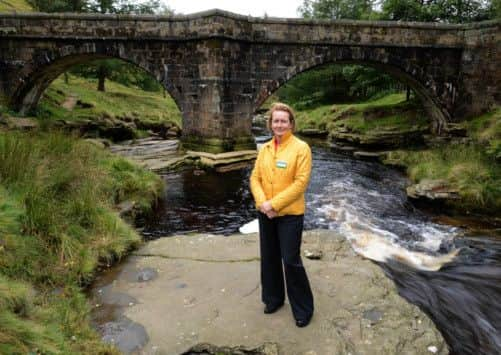

The aim of its 50-year blueprint, launched last week by the trust’s director general Dame Helen Ghosh, is to restore one of the most stunning parts of the Peak District and undo decades of damage to create “a landscape of healthy peat bogs, diverse heaths and natural woodland rich in wildlife.”

The trust’s “vision” is to return 10,000 hectares of land it looks after in the High Peak moors to its former glory. This area covers picture-postcard sites such as the upper Derwent Valley – home of Ladybower reservoir – Kinder Scout and Jacob’s Ladder.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMore than 10 million visit the national park each year, beguiled by its stunning natural beauty. But its beauty belies the need for urgent action and the conservation charity is under no illusions about the scale of the challenge it faces if the natural habitats on its 40 square miles of land are to continue to flourish in an evolving environment.

The fact that so much emphasis is being placed on the landmark initiative shows just how much is at stake. “It’s a really important project for places like Kinder Scout and having a body like the National Trust making such a long term commitment will benefit the whole area,” says Ruth Chambers, the Ramblers policy consultant.

The Peak District is home to beautiful, but fragile, landscapes. One of the big problems is worsening soil erosion, although there’s no one single cause.

“Our pollution mix has changed over the last 50 years. We have changing weather and over-grazing on the moors, which has made a major difference,” says Chambers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The landscape doesn’t stand still in time, it’s constantly evolving and peat landscapes are incredibly rare, they’re our rainforests, and that’s why it’s very important we help conserve them.”

She says it’s important the landscape becomes more resilient, which is why there’s so much interest in what the Trust is doing. “There are lots of other peat erosion projects going on, but what’s exciting about this is the long term impact it’s hopefully going to have.”

We perhaps don’t realise that what happens on our upland peat bogs can impact directly on us. “At the moment peat is getting eroded and washed away and ending up in water courses and our water supplies. This creates added costs for water companies and bill payers. It’s just like any other problem, if you tackle it further upstream it’s cheaper and more effective,” she says.

Liz Ballard, chief executive for the Wildlife Trust for Sheffield and Rotherham, says there’s a lot riding on the project. “Instead of doing something piecemeal this is a much broader vision for the conservation of habitat and wildlife,” she says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Peak District is home to a rich variety of birds including wading birds like curlew and lapwing that nest on the moorlands, and plans are afoot to reintroduce black grouse which disappeared from the moors in the 1990s. It’s something Ballard feels encapsulates the significance of the trust’s project.

“The reintroduction of black grouse would be such an achievement. It often feels like we’re just trying to hold the fort and stop things getting worse. But with this they’re actually looking at bringing in additional benefits and creating new habitats. The challenge will be in the delivery,” she says.

There are some huge challenges ahead such as eroding peat, drying out bogs, lost woodland and dwindling heathland vegetation, that need to be addressed. Some people might be surprised by the level of decline and question how we’ve ended up in this situation. However, Patrick Begg, the National Trust’s rural enterprises director, says there’s no single reason for it.

“In the post-war period there was pressure to produce more from the land and new crops were planted in upland areas, and more cows and sheep were introduced which hugely degraded the habitat,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut Begg doesn’t believe people have taken the landscape here for granted. “A lot of people care passionately about it, walkers, farmers and conservationists. I don’t think there’s been complacency, times change and our appreciation of what the land is capable of doing changes. It’s hard to blame past generations for getting it wrong, it’s more about realising the need to do something,” he says.

Restoration of the peat-rich bogs are a major part of the project. The peat found in the uplands of the UK has as much carbon as the forests of Britain and France combined, while the High Peak moors alone store the equivalent of two years carbon emissions from Sheffield.

The problem is the combination of factors causing the erosion mean rather than storing carbon as it should, the peat is releasing it into the atmosphere. “Instead of being carbon sinks they’re becoming agents of climate change,” explains Begg.

Reversing this is isn’t going to be easy. “We’ve got a big task to stop the erosion and get the peat bogs and moors back to the position where they’re locking up carbon and not accelerating climate change.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt won’t happen overnight, though, hence the reason for such a lengthy scheme. “Originally we started with 30 years, but we realised it would take 50 years to see fundamental change.”

One of the key areas of work will focus on blocking gullies that have eroded the landscape and re-seeding plants on the moorland tops. The trust will carry out £500,000 worth of moorland restoration work per year over the next couple of years, funded in part by Natural England, the Environment Agency’s Catchment Restoration Fund and the Moorlife Project, among others.

Further down the road the aim is to have 800 hectares of new, or restored, clough and valley woodland over the next 50 years.

If a Forestry Commission grant is secured there are plans to return other areas to how they might have looked 150 years ago with the creation of ribbons of broadleaf oak and ash trees.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We want to have shelter corridors for wildlife and to knit the soils together to help create a very different landscape, particularly in the valleys, but a much more natural one,” says Begg.

“The restoration is about wildlife and habitat and the beauty of the landscape, but at the same time it’s about putting the area back into good heart.”

All eyes will be on the Peak District and this profoundly ambitious conservation scheme in the coming years, because if it’s successful it could transform the way we manage some of our most cherished landscapes in the future.

A natural treasure trove

The Peak District National Park was the first of Britain’s 15 national parks, founded in 1951.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt reaches into five counties: Derbyshire, Cheshire, Staffordshire, Yorkshire and Greater Manchester, and is the country’s most accessible national park with an estimated 20 million people living within one hour’s journey.

The park covers an area stretching 555 sq miles and attracts more than 10 million visitors a year.

It has 1,600 miles of public rights of way (footpaths, bridleways and tracks) including 64 miles accessible to disabled people.

More than a third of the national park is designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).