The hidden underground world of Yorkshire's caverns

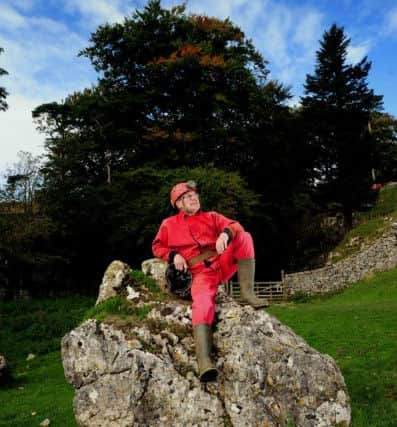

“Thailand’s true-life drama had it all,” says Alan Speight, a well-regarded figure in the caving world and a former chairman of the Yorkshire Subterranean Society (YSS).

“People trapped in flooded passages. Cavers intent on rescuing them. Problems along the way. Such rescues have long happened in the other caving areas of Britain too – like the Peak District, Brecon Beacons and Mendip Hills.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt has also shone a spotlight on England’s expertise in caving. “Two of this country’s cave divers, John Volanthen and Richard Stanton, were the first to find the lads who had been trapped underground for nine days,” says Alan.

He says signs suggest there has been a subsequent increase in people enquiring about joining caving clubs. According to the British Caving Association, there are already up to 4,000 regular cavers in the UK, while around 70,000 people are taken on instructor-led courses into Yorkshire Dales caves each year.

Books on caving and caving videos are increasingly being requested in public libraries.

Show caves where customers pay to enter floodlit caves, like White Scar Cave, near Ingleton, have had an extra busy summer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMore families have discovered going underground is an ideal bonding exercise. This goes, too, for the numerous parties that outdoor pursuits centres are being asked to organise when there are caves in their area.

Not since the pioneering descent of Gaping Gill using a rope ladder and a candle by French speleologist Edouard Martel in 1895 has caving so caught the public’s imagination.

Back then, the news broke that here in the West Riding was a cavern so vast its main chamber would swallow St Paul’s Cathedral.

“G G” as it is affectionately known by cavers, is the scene of descents in a winch-powered chair set up by the Craven and Bradford pothole clubs twice a year. “Members of the public can descend for a fee, because the main chamber is well worth seeing when you are suspended like a spider on a thread,” says Alan.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFast forward to 2018. “Hats off to the Thai authorities. They had the nouse to act on the advice given by the UK cavers who volunteered to assist and who were given a free hand.

“I thought the media managed the Thailand story very well, and showed caving up in the best possible light. Everyone was seen working together in a thoroughly professional way at what basically is their hobby.”

He should know, having himself been involved in the penultimate stage of the discovery of the missing link in Britain’s longest cave system.

Together with Phil Parker, a quantity surveyor from Leeds, he will not forget that auspicious time in the 53 miles-long Three Counties System.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEasegill Caverns in Cumbria; Lost John’s Cave, Ireby Cavern and Notts Pots in Lancashire; and Large Rift Pot in Yorkshire are the cave systems involved in this immense subterranean labyrinth – now ranked as the 26th biggest in the world.

Back in 2008 only one gap remained to be breached – a suspected passage thought to exist between a cave called Notts II Pot and Lost John’s Cave, both underneath Leck Fell in Lancashire.

“Me and Phil took a battery-powered bilge pump into Notts II and emptied an impassable section where the cave roof met water called Bruno Kransky’s Rising Sump.”

The space was too tight for divers to penetrate because of their extra gear. “Water pumped out, we squeezed through a gap a foot high, pushing rocks aside. Ahead was a larger passage with a draught.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Fantastic! We felt we were on our way through to the promised land of Lost John’s Cave, that final elusive missing link.”

However, their excitement was misplaced. “The way ahead was blocked by boulders too big to shift. So frustrating. We had given it our best.”

So near and yet so far...

Other cavers in Notts II Pot later lit 40 joss sticks and the fragrant smoke borne on the draught was sniffed by compatriots waiting on tenterhooks in Lost John’s Cave.

The Three Counties System was finally completed in 2011 – once boulders and silt were shifted, shored up or safeguarded by scaffolding.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCavers have long owned “huts”, as they are known – like the YSS has owned the Old School in Helwith Bridge since 1981.

Near the River Ribble, deep in the cave and pothole-rich Three Peaks country, this splendid club accommodation caters for cyclists and walkers too.

It is indeed a far cry from how the club started out as The Undertakers and comprising a handful of potholers from the Pontefract and Castleford area using primitive rope ladders, boiler suits and acetylene lamps.

“Most early members met at Whitwood Mining and Technical College in Castleford,” says Trevor Tordoff, a founder member who hails from Pontefract – and has a family business retailing outdoor equipment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Some of the tackle was made in night school classes and pooled for club use.”

Today, Alan readily admits to being fixated by the belief that a master cave exists behind the world-famous Malham Cove.

“As a little boy at Rothwell Council school I was fascinated by the water flowing out of Malham Tarn, vanishing into Dry Valley above the Cove, then bubbling out below it,” he said.

“Meanwhile, my longtime friend Mick Burrow and me would pick easy caves out in guidebooks and explore these – like Yordas Cave near Ingleton which was once a show cave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We’d also go to Attermire above Settle, or Chapel-le-Dale near Ribblehead, travelling by coach, agog at what lay ahead. Ninety-eight per cent of cavers like to cave what’s already been explored, as we did then. But two per cent of us have become addicted to the buzz of finding totally new caves.

“We believe there is a big cave system yet to be discovered behind Malham Cove. It’s got water that disappears into the right sort of limestone and which comes out below the cove.

“It’s got faults in the limestone that produce cave passages as detected by harmless dyes like fluorescein. It’s a shame that all attempts to break through so far have been thwarted.”

They came close at Kuling Hole on Malham Moor. “It was from here we had previously dye-tested the water and found it emerged tinted green at the foot of the cove. I was there when we broke through into 300-400 feet of cave passage beyond. When we felt that clean, fresh draught we definitely thought we’d cracked it. And that the cove’s master cave beckoned.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was the tightest squeeze I’d experienced. I had to lose a stone and a half in weight before I got through it. I had to push my battery and helmet ahead of me through the slot – seven inches high at its narrowest point.

“We had told nobody where we were digging– not even our wives for fear they would worry. Yes, we could have got stuck, but I had every confidence cave rescue would have found us.”

To their dismay they were stopped by boulder chokes and passages submerged with water.

He says that during this summer’s drought he and companions managed to explore passages in neighbouring Pikedaw Hill that looked promising.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNo cavers had ever entered these before. But once again the secret to unlocking a master cave behind the Cove came to nought.

“It’s like searching for the last frontier of the totally unknown,” he adds as I depart. “One day I’m sure we will finally get there. Or someone else will.”