The mouse that roared

In a quiet corner of the North Yorkshire Moors National Park, a family-run firm has been producing solid oak furniture using the same handheld tools and traditional techniques for more than 130 years.

There was a time when every village had a joiner, blacksmith and other skilled craftsmen, but most disappeared forever when the industrial revolution dawned. Somehow Robert Thompson’s Craftsmen Ltd emerged unscathed, resisting the pressure to switch to labour-saving machinery. The business is still based on the same site in the tiny village of Kilburn and the only thing that has changed significantly is its customer base, which was once limited to villagers and local churches. Today it includes the likes of the Queen of Jordan, Rothschilds Investment Bank and other high-profile clients, who commission bespoke, made-to-measure pieces.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFamed for its trademark mouse carvings, which adorn every piece of furniture produced, the company is committed to handing age-old skills down to the next generation through its apprenticeship scheme.

It’s a subject that managing director Ian Thompson-Cartwright – the great-grandson of the company’s famous founder Robert ‘Mouse Man’ Thompson – is passionate about.

He explained: “Everyone is gifted at something; it’s a matter of bringing that gift out. The future of the business lies with the apprentices of today; they are the craftsmen of tomorrow. Some young people still want to learn practical skills, not everyone is academic. I think there’s too much focus on further education and some young people simply want to get out there and learn a trade.

“As a country, we’ve been through a lot of changes. Grants are not so readily available for people to go to university and there’s no guarantee of a job at the end of it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“If they do get a job, they could be working for 20 years to pay off student loans. Here they can start earning from day one and learn skills that they can take with them for the rest of their lives. Plus, at the end of each week, they can step back and say ‘I created that’.”

Ian admits that a high level of commitment is required from apprentices and it’s not for everyone, adding: “It can be difficult to encourage people to take the leap of faith; some don’t want to have to train for four years. It’s not a five-minute wonder, it’s a slow process.”

The company works with local schools to try to capture the imagination of students at a young age by offering them two-week work experience placements.

Ian said: “Those who are interested can then apply to be an apprentice when they leave school. If chosen, they complete an initial three-month training programme and are then reassessed. If they’ve progressed sufficiently, they’re given a full contract and embark on a four-year apprenticeship.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The training is all carried out in-house; they work on a one-to-one basis with our craftsmen, who all have their own ways of doing things.

“Working with them each in turn enables the apprentices to find out what works best for them.”

A number of apprentices commute considerable distances to work for the company , but, for 20-year-old Andy Wadkins, the 80-mile round trip to work each day is well worth it for the unique opportunity to work with his hands.

He said: “I enjoyed woodwork at school but so much is done by machines now. It’s good to be able to use hand tools.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s a view shared by Grant Taylor, 22, of Leeming Bar, who, like Andy, is approximately halfway through his apprenticeship. He said: “There are not many places that give you the chance to work with your hands.”

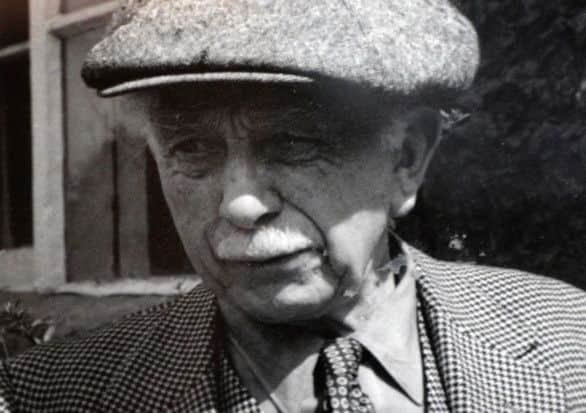

Their stories echo the early life of Robert Thompson himself, who as a 14-year-old was encouraged by his father to go off to West Yorkshire to train as an engineer.

Ian explained: “Robert’s father saw that the world was changing and thought he should go into engineering. In those days, getting to Cleakheaton would have been a lengthy journey that involved lots of buses and Robert had to stop off at Ripon, where he spent a lot of time in the cathedral admiring the carvings. He was really just killing time, but he would sit sketching and wanted to recreate what he’d seen.

“As the village joiner, Robert’s father supplied people will all their basic requirements. Robert wanted to take it further and had aspirations to do great things. He was entirely self-taught.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen Robert’s father died, he took over the family business and, following his own path, made it what it is today. In the early years he experimented with various different styles, but by the 1920s the famous mouse had begun to appear in his work.

The inspiration behind it is not entirely clear, but Ian is able to shed some light on its origins: “According to a story told by Robert himself, one of his craftsmen remarked that they were ‘all as poor as church mice’ and Robert carved a mouse into the church screen that he was working on.”

The trademark mouse is one of the first things that apprentices learn to carve, but each craftsman will develop their own unique take on it.

Ian revealed: “Each one is instantly recognisable but different, depending on who carved it. They’re rather like the signature of each individual craftsman.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs we tour the workshop, Richard Warren, 19, of Yarm proudly shows us a nut dish he’s made with a mouse perched on the rim. As the newest apprentice, he only joined the company a year ago but picked up the skills quickly and was producing smaller items like this within four months. As apprentices grow in experience, they’re allowed to work on larger, more complex jobs.

One of his colleagues nearby is using an adze, a simple tool dating back to the Stone Age, to create a subtle honeycomb-like effect on the surface of a table. Another of the company’s trademarks, Ian explains that it’s a largely a decorative effect but also deflects the light in a way that makes scratches to the surface of the wood less obvious. It also means that damage to a small area can easily be repaired, without affecting the entire table top.

Like the young men learning their trade in his workshop today, Ian also had to complete an apprenticeship and knows how to make each of the items produced by the company. He is one of five family members employed by the business today, and spends much of his time designing bespoke items for customers.

During the last 20 years, Ian and his family have developed a Visitor Centre, complete with shop and café, in Robert Thompson’s original workshop and adjoining blacksmith shop. There you can see early examples of the ‘Mouse Man’s’ work, as well as unusual pieces that have been bequeathed to the visitor centre, or that Ian and his family have bought back.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s a fascinating insight into the life of an incredibly forward-thinking man, who, recognised that traditional craftsmanship still had its place. But his business has also fully embraced the modern age to export its furniture around the globe.

For more information and details of opening times, visit: www.robertthompsons.co.uk