Alwyn Turner: Decade that shaped today’s out-of-touch political class

The attempt to avoid this inevitable humiliation had seen billions being thrown at the currency markets, and an increase in interest rates from 10 to 15 per cent in a single day. None of it had worked.

Black Wednesday effectively sounded the political death-knell for Major, who had scored a surprise victory in the general election just five months earlier. The government limped on for another four-and-a-half years, but it never recovered from the defeat. It was “in office but not in power”, as Lamont himself was to put it. Labour took a lead in the opinion polls and, with only one brief blip, held it for well over a decade.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs we approach the 21st anniversary of that traumatic day, it all seems a very long time ago, fading into the realm of history. But that photo of a visibly shell-shocked Lamont, announcing sterling’s capitulation, also suggests a line of continuity through to the present. Because standing off to one side of the devalued chancellor – as though not wanting to be too closely associated – is his adviser and speech-writer, a 25-year-old David Cameron.

Cameron himself, already being touted in The Times as “one of the brightest young men in the party”, survived Black Wednesday better than his boss did. Lamont was sacked in the spring of 1993, but Cameron simply stepped sideways to become political adviser to the new home secretary, Michael Howard, and then continued his upwardly mobile progress.

Similarly, when the Major government was plunged into yet another crisis, with the revelation in 1996 that BSE – “mad cow disease” – might have spread from cattle to humans, it was not necessarily the happiest of times for a 24-year-old adviser at the Ministry of Agriculture.

But while his fedora-wearing minister, Douglas Hogg, was roundly ridiculed for ineffectiveness (and later for asking the taxpayer to subsidise his moat-cleaning), George Osborne went on to bigger and perhaps better things.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile, on the other side of the political divide, the mid-1990s were also populated by earnest young advisers, who would one day occupy the front benches. Before it came to refer to New Labour’s women MPs, the term “Blair’s babes” was coined to describe the twenty-something likes of Ed Balls, Yvette Cooper and David and Ed Miliband, clustered around Tony Blair and Gordon Brown in opposition.

Conservative and Labour alike, they turned their backs on ideology and aspired simply to be managers. “This generation exudes an air of responsibility, but I don’t think there is any visionary feel or coherent philosophy,” remarked one of the young Tories in 1993.

This was the beginning of what was soon identified as a new political class, comprised of interchangeable figures who’d moved smoothly from university to political adviser or think tank researcher, and then on to parliament and cabinet.

Even in those early days, they were far from representative of their generation, let alone of the public more widely.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMore visible at the time were the anti-roads protesters like Daniel Hooper, better known as Swampy, the predecessors of those currently trying to stop fracking.

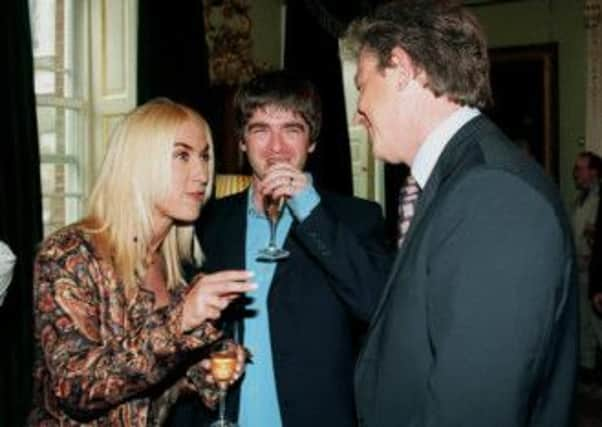

Then there were the multitudes attending raves – whether legal or not – or soaking up the popular culture of Britpop and Cool Britannia. Blair made sure to flaunt his Fender Stratocaster as he clambered aboard the Oasis-Blur bandwagon, though his overtures were swiftly rebuffed. “Betrayed” read the headline in the NME, over a picture of the new prime minister.

Notably, however, none of those young advisers seemed to have any connection with an increasingly democratised culture.

Remote and removed from the electorate, they’ve gone on to turn the House of Commons into what increasingly looks like a students’ debating chamber, while complaining that there’s a mood of “anti-politics” abroad in the country. The one strength that might be expected – the ability to generate new ideas and policies – is scarcely evident in this excitable yet homogenised world

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut if there is a difference between the two front benches, it’s an attitude rooted in those experiences of the mid-1990s. Where Cameron and Osborne witnessed at close quarters the spectacular implosion of a party that once believed it was predestined to power, by the time Ed Miliband and Ed Balls were admitted to the inner circles of New Labour, their party was already coasting into government. The heavy lifting had been done by Neil Kinnock and John Smith, while the Tories’ vicious infighting over Europe merely made a Labour victory at the polls more certain. Even the nightmare of Gordon Brown’s premiership had personal compensations for the two Eds. They were promoted into the cabinet, barely two years after entering Parliament. Better yet, they were given the energy and education portfolios, distanced from the banking crisis that was about to break.

Now, after a summer in which it has seemed the only alternative voice is that of the Church of England, it is hard to escape the conclusion that the current Labour leadership has too little experience of hard times to know how to respond when the tide turns. By contrast, the main complaint against Cameron in the early years of the coalition was that he was too fond of “chillaxing”.

What’s not always recognised is that the political character of the Tory leadership was formed in those desperate days of the 1990s. Osborne may have come under fire for his “pasty tax” last year, but it was nothing to compare with the headlines he faced during the BSE crisis. And 21 years on from Black Wednesday, Cameron can reflect that things could only get better, and that they have done so.

It’s also worth remembering that in all those intervening years the Conservatives have contested four general elections and failed to win a single one. It takes a lot to recover from the impression of economic ineptitude. And that remains the real challenge for a post-Brown Labour Party led by the graduates of the 1990s.

• Alwyn W Turner is the author of A Classless Society: Britain in the 1990s, published by Aurum Press, price £25.