My lessons as a roving Yorkshire vicar – Matt Woodcock

It was a glorious morning and I looked forward to giving thanks to God for the gift of being alive.

About an hour later, I walked out of that gloomy church feeling like my good mood had been sucked out of me by one of those happiness-devouring Dementor characters from the Harry Potter books. It was grim.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA few things struck me as I sat there on the rock-hard pew – cold, uncomfortable and bored. No-one looked like they wanted to be there. No-one.

Not the ‘welcomer’ on the door handing out the hymn books. Not the light smattering of worshippers sitting as far away from each other as possible. Definitely not the Vicar. He barely looked up as he mumbled the prayers and flowery liturgy.

And the organist? I’m not convinced he was even conscious. This can’t be it, I thought. This can’t be what God intended for His church?

Where was the joy, the sense of community – the merest hint that the Christian faith might be ‘‘good news’’? The experience stayed with me as I went on to become a Reverend myself. It came to represent the opposite of what I thought church should be like.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSince then, I’ve worshipped at, worked with and reflected on many different Anglican churches of all traditions and contexts. I’ve discovered that while numbers are often low and the age profile high, the willingness and capacity to do good is enormous.

Recent figures showed that 16,000 churches were running or supporting 35,000 projects before the Covid-19 pandemic, including food banks, parent-toddler groups, and lunch clubs. Another study found UK churches provided £12.4bn worth of essential support to communities over a 12-month period.

Yet, for all that amazing work, actual church attendance has continued to decline. Since 1970, Church of England congregations have halved and fewer than 700,000 people now attend our Sunday services.

Perhaps most worryingly of all, 38 per cent of our churches have no-one under the age of 16 and CoE affiliation has fallen to just two per cent among adults aged 18 to 24 years. It’s little wonder that there are projects targeting younger generations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn my own Diocese of York, I’m one of a new breed of ‘‘Multiply Ministers’’ – deployed in places like York, Scarborough, Malton and Hull – with a brief to build new Christian communities for those in their 20s, 30s and 40s. We’re expected to use creative ways to connect with our predominantly secular culture.

My first clergy assignment at Holy Trinity Church, in the centre of Kingston Upon Hull, showed me what was possible. The largest parish church in the UK but with a small congregation and losing more than £1,000 a week, our little clergy team was the last throw of the dice for this 700-year-old institution.

My latest book, Being Reverend, is a diary of my first whirlwind 18 months ministering there. It’s a story about change, really – and the lengths we’d go to to make it happen. Those years trying to turn things around were the wildest, most fun and faith-filled of my life.

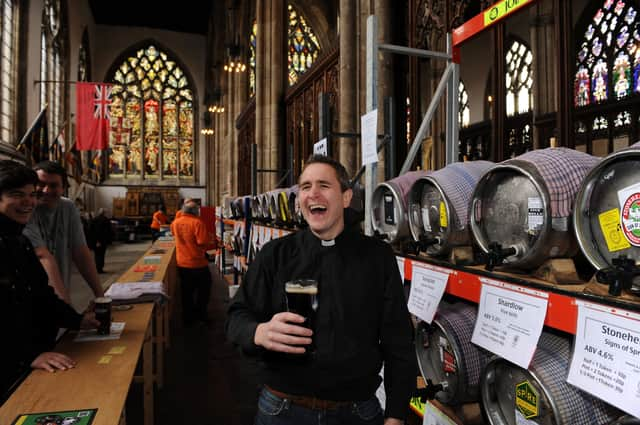

It was fascinating to see the impact of hosting things like a beer festival, rock gigs and Christmas nativities with real camels. As our visitor numbers swelled, so did our Sunday congregations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt convinced me of the need to be relentlessly welcoming and invitational regardless of belief or background. To be a community where it was easy to make friends and to create Sunday worship that was relevant, fun and sacred.

Unlikely blokes like Kenny – one of the beer festival doormen – began to join in. He told me he’d always wondered what a worship service was like. “Why not see for yourself on Sunday?” I asked him. He replied: “I didn’t think I’d be allowed.” Kenny ended up joining the choir – proudly singing his heart out on Sunday mornings.

Holy Trinity has since undergone a £4.5m transformation project and, in 2017, was rededicated as ‘‘Hull Minster’’ to reflect its contribution to the community. More importantly, lads like Kenny still get invited.

My Hull years taught me that when churches have the courage to change, take creative risks and put people’s needs before their own ecclesiastical self-indulgences, they have the potential to not just survive but flourish.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf course Covid-19 has forced churches to adapt and change – quickly. The pandemic is having big financial implications. Lockdown also meant that thousands of previously technophobic clergy turned to YouTube and Zoom minister to a virtual flock. Front room church has proved popular.

While the future remains uncertain, the new Archbishop of York, Stephen Cottrell, has heralded a radical one. At his enthronement service, he called for a ‘‘revolution’’ in the Church of England. The need to ‘‘let go’’ of ‘‘pomposity’’, ‘‘privilege’’ and ‘‘power’’ in order to create an open table at which everyone is invited to hear a ‘‘gospel of love’’.

Amen to that. I’m all for a revolution – particularly a joy-filled one.

Matt Woodcock is a Yorkshire vicar and author of ‘Being Reverend: A Diary’ published by Church House Publishing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSupport The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today. Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you’ll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers. Click here to subscribe.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.