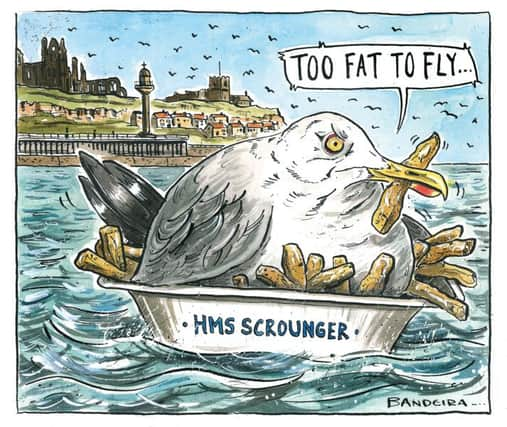

Neil McNicholas: Why it’s time to cull these greedy seagulls

If you look a seagull squarely in the eye it is immediately apparent that there is no love lost.

It will return your look with a steely glare that tells you this bird has but one concern, one priority – food.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike the current breed of wood-pigeons, the herring gull that is the scourge of our seaside resorts has become oversized and quite capable of causing serious harm to anyone it decides to “attack” – as it will in its efforts to relieve them of their fish and chips, sandwiches, pasties or anything else that takes its fancy.

Areas of flat roofing around my Whitby church were regularly covered in chicken bones – the result of gulls raiding litter bins for fast food left-overs.

In their search for a source of food, they have strayed far from the sea. They flock over domestic waste tips in huge numbers, clearly having developed a taste for all sorts of edibles other than fish.

I once saw flocks of gulls half way across the Pennines – miles from any open water. You have to wonder whether the name “sea” gull is now a misnomer and whether some have ever seen the sea let alone a fish. They have become scroungers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo why, as I understand it, do they still have protected status? They are everywhere, eating everything, and in huge numbers. I could watch a popular nesting site from my window and every year the two gulls – probably the same two – would produce two or three youngsters and this was happening in nesting sites all over the town.

As a result, the number of gulls was obviously increasing exponentially season by season – increasing also the demand for food and therefore, no doubt, making them ever more aggressive in that quest.

For a brief period after the young gulls fledged, most would head out to sea to fatten up for the winter, but they always came back again and Whitby would submerge under its ever-expanding colony of gulls and no one could do anything about it because they were protected.

The annual debate of the pros and cons of culling would be heard (though largely drowned out by the screeching and squawking of the very gulls under discussion) but nothing would ever happen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe pseudo-Hitchcock experience of visitors to the town who unknowingly wander along the street with fish and chips in-hand, isn’t helped by those – generally also visitors – who actually feed the gulls despite the signs asking them not to.

How anyone, faced with that steely-eyed stare, could be under the misapprehension that said gulls are in need of a feed is beyond me.

And behind them is the backdrop of the North Sea – 750,000 square kilometres of fish – as if the gulls were incapable of finding anything to eat in the way nature intended them to.

Yes, we know all about the reality that if you live by the sea you should expect seagulls (and all that comes with them – or, rather, that falls from them), but if numbers were more manageable, more controlled, then the odds of being deposited upon would be vastly reduced.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the moment, however, in towns like Whitby all around our coast, the odds are stacked in the seagulls’ favour. Maybe people should be allowed to carry paintball guns in order to give them a taste of their own medicine.

Even if we accept that if you live by the sea you should expect seagulls, and if we also accept that the mix of gulls and people is going to have unfortunate consequences from time to time, the situation isn’t helped at all by those who encourage the interaction by feeding them.

And if they are visitors and ignore the signs asking people not to feed the gulls, then they only have themselves to blame if they act more like vultures than budgies.

Signs or no signs, common sense should surely dictate that if you don’t want to suffer the attacks of gulls, or other unpleasant consequences of large birds flying overhead, then you don’t encourage their interaction with people in the first place.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it would also seem to be a matter of common sense that gull numbers need to be controlled as more young are hatched every year and then those young have their own young the year after and so on and so on.

Gulls don’t need to be protected – they are quite capable of protecting themselves – and meanwhile a policy of humanely culling excess numbers would seem to make eminent sense and surely the simplest method would be to remove and destroy eggs before they hatch.

Or are we just too gullible?

Father Neil McNicholas is a parish priest in Yarm. He used to serve in Whitby.