North-South divide can be explained by these historical events – James Hawes

Yet somehow, almost immediately, a question which should be one for medicine and science – how to combat a worldwide pandemic – has mutated into the cry which has troubled the Southern rulers of England every few generations since the death of Athelstan in 939 AD: the North is in revolt, with Andy Burnham and the Red Wall Tories, notionally mortal enemies, singing from the same hymn-sheet.

It’s amazing – but only if you believe, as many people inexplicably still seem to believe, that the North-South divide only began with Margaret Thatcher. On the contrary. It is the abiding theme of all English history. We English have been split by the Jurassic Divide in Britain’s rocks and soils more or less from the day we disembarked from Germany.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe line of the divide is practically the line of the Trent. That river, which wasn’t bridged until the 10th century, is known to archaeologists as the split between different kinds of fortifications in the Iron Age and between the truly Romanised and barely-Romanised parts of England.

Geology is fate, and when we English arrived here from c.400AD onwards, the same line rapidly began to separate us. By the time the Venerable Bede sat down in Jarrow to write the first history of the English people in c730, it was obvious (he says it nine times!) that there was a basic difference between the Northern and Southern English.

The church of Rome itself, ever-keen on unity and central control, recognised this in 735AD when it accepted the lasting split in the English Church between Canterbury and York.

Since then, history has only made the North, often centred on York itself, more different. The Viking invasions and settlements rammed home the North-South divide in spades. Harald Hardrada of Norway landed in the North in 1066 correctly guessing that he would be greeted as a liberator from Southern rule, not as a foreign invader: it was the North-South divide which doomed England to Conquest.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd while the South appeared to simply accept Norman rule after Hastings, the North rebelled, and suffered such terrible punishment in the Harrying of the North that, almost 20 years later, the Domesday Book wrote off a third of all the land in Yorkshire as “waste”.

For 300 years afterwards, all England was ruled by a French-speaking caste who plastered over the old cracks. But as they themselves became more and more English, the North-South divide broke through again. And it’s never gone away. At times it has looked like dynastic fights, at times like religious differences, at times like politics – but really, it’s always about the same thing: Will the North be dominated by the South?

In 1405, the Percys seriously proposed to create a separate Northern kingdom forever. The Wars of the Roses was at heart all about that divide. Richard III became king only because he had his own power-base in York as leader of the Council of the North.

The Reformation tried to centralise all England in the hands of a new, Southern elite, so naturally, the North resisted. When King Charles I fled London in the lead-up to the Civil War, he naturally hurried to the ancient, alternative capital of England – to York. As late as 1745, the Stuarts expected the North to greet their Scottish armies as liberators. The Chartist movement was another attempt – which is why it proposed setting up an alternative Parliament in Manchester.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1884, large numbers of ordinary people finally got the vote and immediately, the English began to vote on these ancient, tribal lines. The South of England became, and stayed, a virtually impregnable Tory bloc, while the Northerners voted otherwise, and looked for alliances with the Celts, to outgun them: we call that alliance, which lasted until 2015, when the Scots deserted it, “the Labour Party”.

So when you look at this broad sweep of English history, the events of this autumn should really come as no surprise. Whatever the superficial names of the parties, the force which has mysteriously united Andy Burnham and the Red Wall Tories is in truth the oldest, simplest force in our politics.

And it’s not going away.

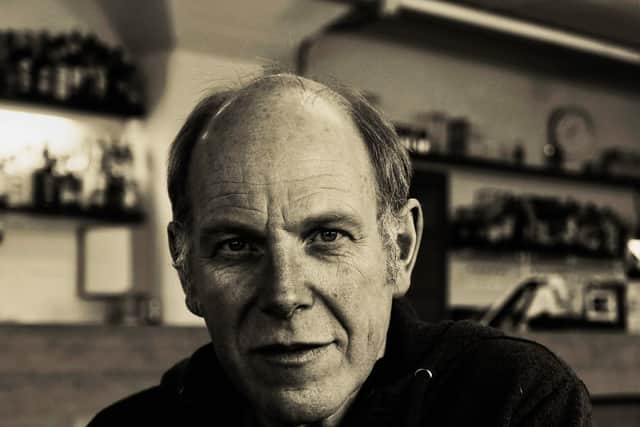

James Hawes is author of the The Shortest History of England.

Support The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today. Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you’ll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers. Click here to subscribe.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.