Progress has been a double-edged sword for journalism - David Behrens

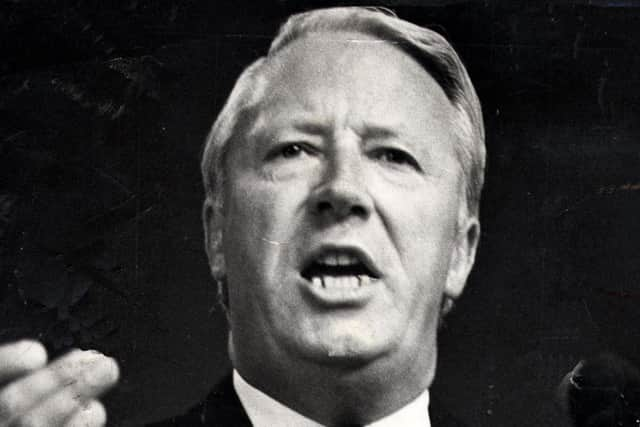

It was official: Britain was shut for four days of the week. Ted Heath’s draconian measures to save electricity meant that factories and offices could be lit and heated for only three consecutive days at a time. TV broadcasting ended with News at Ten. Shops that had only recently restocked candles after the previous year’s blackouts, ran out again.

Had Heath not baulked at denying us the Andy Stewart Hogmanay show that Grampian TV inflicted upon us each year, he would have cancelled the holidays completely.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was the miners’ overtime ban, which effectively halved coal production, that led directly to what we took to calling the Three-Day Week – but the writing was already on the wall. A few months earlier we had almost run out of oil when middle-eastern nations began restricting supplies to countries that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War. There wasn’t a petrol station in the land without a queue on the forecourt.

That last detail serves as a reminder of how little, as well as how much, the world has changed.

For me, that winter of 1974 was a watershed. On January 1, I was still a student; by March 8 when five-day working was allowed to resume, I had become a journalist – a title that sticks to me to this day, despite all the evidence.

By that time also, Ted Heath had become an ex-prime minister, having unwisely called an election to determine who governed Britain only to discover it wasn’t him.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe country he left behind was scarcely governable by anyone. The three-day week was just a foretaste of even worse times to come and before the decade was out you’d have to consult your evening paper to find out what time your street was going to be blacked out that night.

All of which made it a good time to be a journalist. Everyone read newspapers, usually two a day, and it was print, not radio or TV, that was considered the medium of record.

Jobs were as bountiful as apples in August. I had been able to pick and choose my first newspaper job from a handful of offers and when I moved from a weekly to a daily title I could almost name my own terms.

But my elders and betters didn’t see it that way. “We don’t have half the vacancies we had five years ago,” I was told more than once by news editors who blamed local radio and the threat of cable TV for what they saw as another phase in a long and steady decline.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey had a point; little more than a decade earlier there had been two evening newspapers in most large towns. In Yorkshire there were two morning papers besides the one you’re reading now. Mergers and consolidation saw off the others.

Nevertheless, there were more than two dozen reporters on the evening paper I joined in 1977 and it sold more copies per night than it does now in a month.

It is technology that has changed all that. When I began writing for the national papers every story had to be dictated to a copytaker on the other end of the phone and then typeset by someone else. The phone calls had to be connected by an operator because otherwise you’d need to feed tuppenny coins into phone boxes that smelled of cats. And the whole process had to be repeated for each paper before some rival reporter beat you to the punch.

Today every link in that chain has been removed. Reporters transmit their words to the world in an instant. Is that progress? I’m afraid so.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut I think what has changed most about journalism is its reliance for stories on external agents with axes to grind: charities and pressure groups forecasting dire consequences unless warnings are heeded; politicians briefing against other politicians; surveys and polls that are little more than adverts for whoever commissioned them.

There was an element of that 50 years ago but it didn’t dominate the news agenda in the way it does now. That was because there were more people in the field reporting on what was happening, not repeating what might happen. Their numbers have thinned in recent years and the emergence of artificial intelligence might see them off completely.

Yet technology is also an enabler that creates better jobs for those in a position to follow the flow rather than fight it. The miners’ leaders learned that long ago; journalism is still getting its head around the idea.

For now, evolution has destined that TV can remain on air beyond 10.30 and that Jools Holland, not Andy Stewart, will be in charge of the Hogmanay festivities. That, I think we can agree, is progress.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.