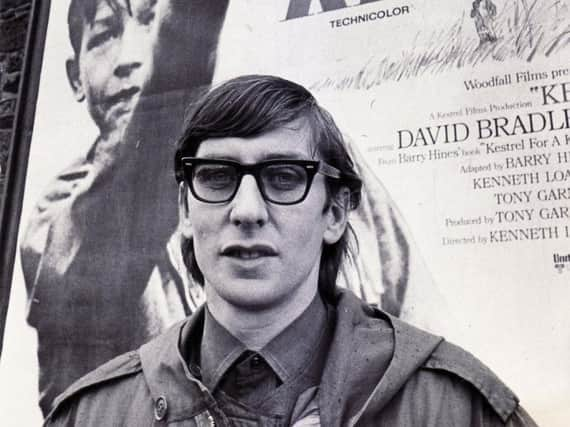

Why I warmed to Greg Davies' documentary Looking For Kes - Anthony Clavane

I’ve been obsessed with Kes for several decades now. Ever since I saw the movie, and was blown away by Billy Casper’s cheeky, scrawny, against-the-odds, Yorkshire defiance.

Ever since I read the novel it was based on, Barry Hines’ unsurpassable A Kestrel For A Knave, which is no longer – outrageously – on the school curriculum.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEver since I discovered that Hines, a pioneering working-class Yorkshire writer, was as passionate about football as he was about writing.

So the thought of a southern-based comedy giant (literally, as he’s 6ft 8in) making a flying visit “oop north” to talk to some ordinary Yorkshire folk about the book, its author and the Loach masterpiece filled me with dread.

Ken Loach reflects on Kes half a century on from classic Barnsley-based filmDavies’ breaking-the-fourth wall buffoonery at the beginning of his “investigation” confirmed my worst fears.

As he wandered through Hoyland, near Barnsley, the voiceover quipped: “Here’s me, walking along local streets, just so I could be filmed walking along local streets.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs I listened to this jarring narration – “As you watch me, inexplicably filmed from above, walking up a road” – I wondered why the Inbetweeners actor had been commissioned to make the thing in the first place.

True, his Mr Gilbert comically-sadistic-teacher character in that excellent sitcom was a kind of homage to Brian Glover’s iconic Mr Sugden in Kes.

And, given the nature of modern-day arts TV scheduling, it is unlikely the programme would have been commissioned by the Beeb had it not been presented by a genial, if somewhat patronising, southern-based, celebrity comedy giant.

However, as soon as it became less of a star vehicle and more of an examination of the Penguin Modern Classic’s universal themes, which continue to resonate five decades on, I warmed to the documentary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd, after he got bored with telling us how he’d never made a doc before (yawn), reined in his need to make cringeworthy, semi-humorous asides and stopped banging on about being double the size of everyone he interviewed – I even warmed to Davies.

The Untameable Barry Hines: Sheffield exhibition shows why Kes and Threads creator’s is needed more than everThe former schoolteacher admitted that he’d been on a journey. Now normally, whenever I hear the j-word I reach for the remote.

But his sudden realisation, at the end, that A Kestrel For A Knave was an “angry, defiant novel”, and his subsequent vow that he would campaign to restore it to the school curriculum, actually moved me.

There appeared to be a genuine epiphany when he visited the new Hines exhibition at Sheffield University’s Western Bank Library, curated by Barnsley artists Patrick Murphy and Anton Want, and held in his hands the writer’s original, handwritten drafts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a genuinely hairs-tingling-on-the-back-of-the-neck moment, Dave Forrest, from the university’s School of English, presented Davies with this, and other archive material.

In a recent interview with the Yorkshire Post, Forrest wondered whether today a provincial teacher – as Hines was before he became a successful novelist – would be asked to write a film, let alone “manage to forge a 30-year career writing about ordinary people from South Yorkshire”.

Given the stagnation of social mobility, this seems highly unlikely.

According to a survey on the British public carried out this week by the Sutton Trust in association with YouGov, 49 per cent of the people questioned thought that today’s youth would have a worse life than their parents.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLast year, a think-tank revealed that privately-educated elites continue to dominate the worlds of literature, TV, film and the arts – despite comprising only seven per cent of the population.

As Davies came to realise, Hines’ astonishing novel was not just a way of engaging students who enjoyed reading out the swear words.

It was about untapping potential and, as he put it, “the need for basic decency”. It was about, in Pulp singer Jarvis Cocker’s words, “soaring with your jesses (restraints) off”.

Or, as the late, great Barry Hines would say, it was about enabling children from socially-disadvantaged, left-behind, continually-ignored communities to believe in themselves.

To gain confidence in their creative talents. To spread their wings and fly.