Stephen Naylor: The human case for greater research into Motor Neurone Disease

The diagnosis was devastating. The questions of ‘why?’ and ‘what happens next?’ went unanswered. Yet even then we couldn’t have known how aggressive the disease would be for him. We never imagined that he would lose his battle with it only 102 days later. He died at 6am on December 20.

Amidst the grief and the sheer devastation of losing someone who had an amazing wife, two beautiful young children and his whole life ahead of him, there is an underlying anger for me.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhy do we not know more about this, the cruellest of diseases?

Why is more not being done to find out about it?

Why are we not spending more on finding treatment.

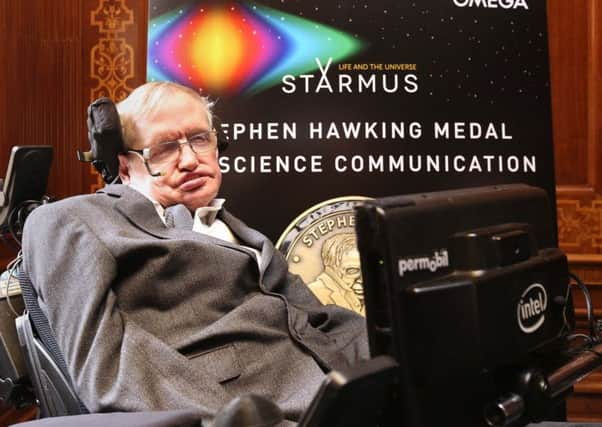

MND is one of those conditions we have all heard of – Professor Stephen Hawking being the most prominent example of someone who has battled the disease – but it’s one we don’t really understand. Part of the reason is that it is actually made up of so many different variations of the disease.

Hawking has lived with his condition for 50 years. Nick had three months. How can the same disease with its same impact affect people in such different ways? The brutal truth is we don’t know. I think we should.

MND is also known as Lou Gehrig disease, named after the New York Yankees baseball star of the 1920s and 1930s who survived three years with the condition until he was 37. He died in 1941 and the causes of MND – and the treatments available – are not much better understood today.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the reasons is because it is, thankfully, so rare – there are estimated to be only 5,000 people in the UK living with the condition at any one time. It affects two in every 100,000 people – that’s 0.002 per cent of the population. It is rare. But Hawking’s survival masks a painful truth, it is devastating – a third die within a year of being diagnosed.

There is both little time for research and, you suspect, little incentive for drugs companies to invest in finding treatments because it’s not financially viable.

That’s also the view of another high profile victim of MND – the rugby union player Doddie Weir. In fact there seems to be a disproportionately large number of sports players who succumb to the disease. Is that a coincidence? Is there a link between high impact sports and developing the condition? It is surely worth researching – but at the moment, no-one seems to be doing so. It may be a painful truth.

Two Government-funded agencies conduct research into MND. The Medical Research Council (MRC) spends approximately £5.3m per year on studies into the disease while the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) spends £52.6m on neurological research – but is, I find oddly, unable to say how much of that is spent on MND research specifically.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCompare those figures to cancer research and you see the stark gap in funding. In the same years, the MRC spent £76.2m – 14 times more – on cancer research while the NIHR spend was £142m.

We should not get into a battle over funding between conditions – no one would want that, and cancer also deserves as much research as possible, but the fact remains that, when you add in the number of charities investing in cancer research and the small but admirable work done by MND charities, it’s hard to escape the conclusion that studies into MND are chronically underfunded.

Yorkshire is, in fact, one of the small beacons of light. The University of Sheffield is home to the MND Care and Research Centre where Nick had visited just days before his death. They are doing pioneering work, with access to clinical trials and research projects. I hope they succeed, they deserve to and we will be ensuring the amazing generosity of people who loved Nick goes to support their work.

No one should have to face what Nick’s family are now having to face. MND robs life from those who have so much to live for. It’s not fair. We should do more, we must do more, to stop it devastating more families in the future.

Stephen Naylor is director of Brighouse communications and strategy consultancy Waverley.