The pity of war and the poet who gave voice to it

On a nice day you might find a few fishermen quietly whiling away the hours here hoping to catch a perch or a pike, or you might bump into a group of walkers exploring the nearby forest.

Another reason why people make a detour to this peaceful corner of northern France is to visit the renovated forester’s house with its newly whitewashed facade.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere on November 3, 1918, a group of officers from the Manchester Regiment were sheltering for the night, including a second lieutenant called Wilfred Owen. The following morning his company was ordered to cross the heavily defended canal and Owen was killed while attempting to lead his men across it.

His death came just a week before the war ended and it is said that his mother received the news on November 11, just as the church bells rang out in celebration for Armistice Day.

It was a tragic end to a young life, Owen was just 25, but in a war bathed in tragedy he could easily have become just another name had it not been for the poems he left behind.

Nowadays, Owen is widely regarded as one of the greatest voices of the First World War. His depiction of soldiers “coughing like hags” and cursing as they wade through “the sludge” of the trenches, not only still resonate with us but colour and shape our view of what Ted Hughes called that “huge, senseless war.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the time of his death, however, only a handful of people knew his name and none could have predicted the posthumous fame that would follow.

Owen was working in France as a language tutor when war broke out. In 1915 he returned to England to enlist in the army and was commissioned into the Manchester Regiment.

Following his training he was sent to the Western Front in January 1917, but after experiencing heavy fighting he was diagnosed with shell-shock. He was evacuated to England and in June arrived at Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh for treatment.

It was here that he famously met Siegfried Sassoon, who was already a published poet. The two men had similar misgivings about the war and Sassoon agreed to look over Owen’s poems, giving him encouragement and introducing him to literary figures such as Robert Graves.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSassoon helped revolutionise Owen’s style and his conception of poetry. But while their friendship and the story of their meeting has become part of literary folklore, what is less well documented is the time Owen spent honing his craft in Yorkshire before returning to the Western Front.

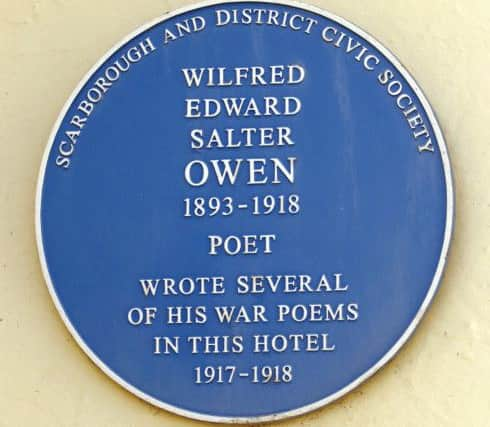

Following his time in Scotland he was sent to Scarborough to aid his recovery. In January 1918, he was billeted in the Clarence Gardens Hotel, now the Clifton Hotel, with a view looking out across the North Bay.

Dr Charles Mundye, from Sheffield Hallam University, says it was here that he started to put Sassoon’s advice into practice.

“Newspaper reports of a terrible mining disaster that January gave Owen the starting point for his first commercially-published poem Miners, a meditation on coal burning in a winter hearth, in which the young dead of the mining disaster are compared with those who ‘worked dark pits / Of war’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The poem begins with the primeval forests from which the coal is made, and ends with thoughts of the centuries to come, comforted by the sacrifices of war – ‘But they will not dream of us poor lads / Lost in the ground’”.

In March, Owen arrived at Ripon Army Camp “an awful camp” and rented a room in a quiet cottage on Borage Lane, away from the city’s training unit which was busily processing squads of young conscripts urgently needed at the front.

Following Sassoon’s advice that he should write about his war experiences he drew on the events that had led to his shell-shock, and during that spring he drafted, wrote and re-worked some of his best known poems.

It was during this fruitful period that he produced poems such as The Send-Off, Mental Cases and possibly Strange Meeting.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite his earlier harrowing experiences, he felt compelled to rejoin his comrades and he returned to France in August 1918 and within a couple of months was awarded the Military Cross for bravery while in action near Amiens.

In his final letter home to his mother, dated October 31, written in the “Smoky Cellar of the Forester’s House”, he gives an insight into their everyday life. In another time it might sound prosaic, but there is a heightened awareness in his tone that perhaps comes from living so closely with death.

There is also a deep and heartfelt sense of admiration for the men around him. He finishes by saying: “I hope you are as warm as I am; as serene in your room as I am here ... Of this I am certain you could not be visited by a band of friends half so fine as surround me here.”

It would be another two years before his single volume of poems, edited by Sassoon, was published. It contains some of the most poignant poetry of the war, including Dulce et Decorum Est and Anthem for Doomed Youth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToday, these poems have become ingrained in people’s minds and Owen’s name lives on, synonymous as it is with the horror and futility of war.

As Owen himself wrote in a draft preface to a collection of poems he had hoped to publish in 1919: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.”