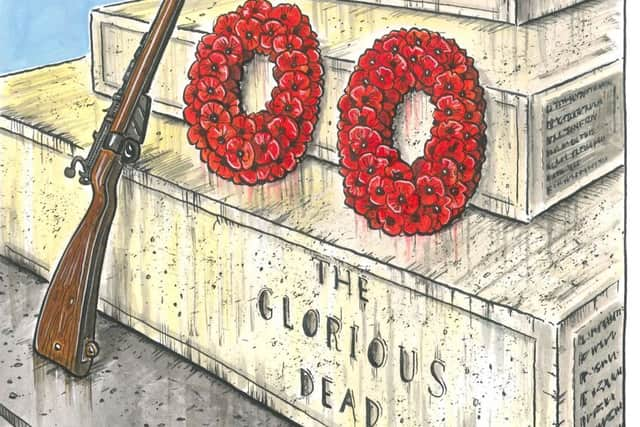

David Blunkett: Grim lessons of First World War that we still need to learn on centenary of Armistice

Fighting continued right up to the last second and many men on both sides lost their lives in the final hours.

But the struggle for survival was not over.

Even before hostilities ceased on the battlefield, another threat to life and well-being struck a deadly blow – Spanish flu.

I’ve always been fascinated by the First World War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot just the indefectible courage in what for much of the time, and for many of the men, was hell on earth, but for much more.

The capacity to endure the normal deprivation of shelter, of warmth, of somewhere dry to sleep tested the human spirit to its very limits.

Those who suffered survived where possible, fought from the trenches and experienced multiple deprivations at the same time as unheard of, and unspeakable, bombardment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen my wife and I went to the war graves in northern France and Belgium with friends in the autumn of 2014, we were struck by the audio-visual presentations, of the impact the constant bombardment must have had, not just on the nervous system, but on the very psyche of those who found themselves in what could only have been thought of as an inferno.

Of course not everyone in the First World War had those kind of experiences.

Some in the upper echelons of the military continued to eat, drink and sleep well.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome found themselves in other theatres of war across the world where there were hellholes such as those endeavouring to build roads in wide-flung outposts of the Balkans and other theatres of war in the Middle East.

But it was those on the Western Front, and the recall which the war graves now offer, which ensures those who gave their lives will never be forgotten.

For instance, when I visited what is now a tranquil glade entitled Railway Cuttings, close to the Sheffield monument, I came across a short letter home kept in a watertight container from a soldier to his family in the Hillsborough district of my city. It offered an insight which I never expected to gain.

Yes, I’m aware that the censor was pretty strict on the letters home but the young man in question never needed to tell his parents that ‘‘this land and these people (the French) are worth fighting for’’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGiven that many soldiers were bewildered as to exactly what they were fighting for and those who led them into the First World War were pretty unclear themselves as to how they got there, this is, in itself, a remarkable message which must have been welcome to this young man’s family.

The consequences arising from the loss of so many young men in their prime, and of course the devastating flu epidemic that I wish to reflect on here, carried forward for generations to come.

As sure as eggs are eggs (as my grandad would say), the losses incurred during and beyond the end of the First World War created the fertile ground from which fascism grew.

It is, of course, true that the slump of the late 20s and early 30s was as much about the speculative behaviour, almost like a second gold rush where millions of people in the United States, and the chain reaction here in Europe, added to the turmoil.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSadly, this is all too reminiscent of a decade ago and the emergence of the global financial meltdown and banking crisis.

Coupled, as it was, almost a hundred years ago with increasingly poor political leadership, inertia and nostalgia for a bygone era, the circumstances were ripe for extremism, with the economic slump following the financial crash on the one hand, and the promise of nationalistic belligerence and simple solutions on the other.

Whilst the rich dance the night away and debutantes look forward to coming out balls, complacent politicians believed that the Empire would go on forever and a ‘‘world fit for heroes’’ could be put off to another day.

Post-war economic activity dropped, the slump took its toll on those who had already suffered grievously both abroad and at home during the First World War, and Hitler came to power in Nazi Germany.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was not – as Harold Macmillan once put it – ‘‘events dear boy, events’’, but a matter of consequences.

Sure, as night follows day, the choices made a hundred years ago at Versailles and the failure to address an entirely new world in the 1920, reverberated through the Second World War, and, in many ways, all the way through to today.

A century is a blink of the eye in the development of creation but to us it should be as immediate as yesterday. In that way we can learn from history rather than living in it and we can ensure that, in doing so, we do our very best to avoid the mistakes of the past.

Lord Blunkett is a Labour peer. Formerly MP for Sheffield Brightside and Hillsborough, he held three senior Cabinet posts in Tony Blair’s government.