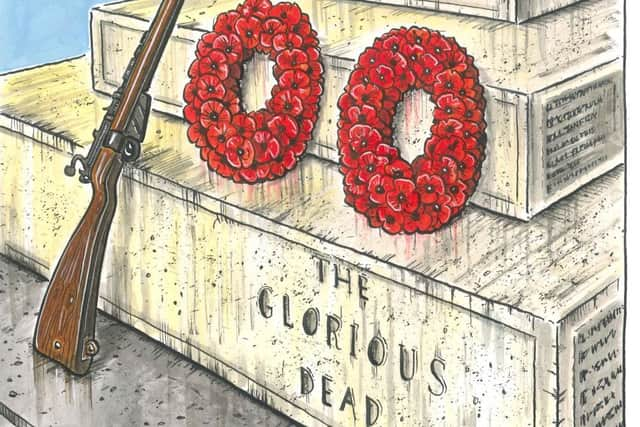

The Yorkshire Post says: Poignancy as Armistice is remembered '“ the resonance of Yorkshire's tribute to the fallen of First World War

One resting place belongs to John Parr, who became the first British soldier to be killed in the Great War when his patrol encountered a German cavalry detachment on August 21, 1914. He was only 17.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet, just feet away at St Symphorien Military Cemetery in Mons, is the grave of Yorkshire soldier George Ellison who, in a tragic twist, was the UK’s last casualty. Aged 40, and a survivor of so many of the conflict’s most attritional battles, he lost his life 90 minutes before the guns were silenced at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918.

Just two of the individuals who made the ultimate sacrifice and never returned from the mass slaughter of the Western Front, it is the proximity of the remains of these fine men which is so haunting – and unfathomable – as Theresa May lay wreaths, amid the falling autumn leaves, on their respective graves at the start of three days of events which will see allies and enemies unite in peace and friendship to mark this unique moment in history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd it’s because at least 15 million soldiers lost their lives between the day Pte Parr fell to his death to the moment of the cruel fate that befell Pte Ellison, whose family back home assumed that he had survived until they were informed of the grim news just before Christmas.

Nevertheless it is such heartbreaking recollections – and the poignancy of their telling – which have helped to define the First World War’s centenary as younger generations have recognised, appreciated and tried to comprehend the sacrifices made in the name of freedom by forebears who were either too modest, or did not have the chance, to recount the full horror of their experiences in Europe’s muddied and bloodied fields of war.

From the moment 888,246 ceramic red poppies, each intended to represent one British or Colonial serviceman killed in the war, were placed outside the Tower of London in 2014, a spirit of respect and reconciliation became a defining theme.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCommunities, large and small, took it upon themselves to organise their own tributes from plaques honouring Victoria Cross heroes to blankets of poppies adorning churches as they traced the stories of names etched on war memorials.

This has been particularly striking in Pte Ellison’s home county where Yorkshire’s military regiments lost 38,889 people – a number which, for comparative purposes, exceeds the maximum capacity of Leeds United’s Elland Road ground.

As the Colonel of The Yorkshire Regiment noted this week, modern soldiers come from the same street, go to the same schools and support the same football teams as the Pals battalions that answered Lord Kitchener’s call to arms.

That so much care and compassion has been taken over each and every tribute is not only testament to the fallen, but the profound societal change which took place during the Great War. Not only were there tales of stoicism as more than two million women worked on the home front while their husbands, fathers and sons were enlisted, but they were finally enfranchised by the Representation of the People Act and the trade union movement took shape.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever the painful irony is that this supposed war to end all wars did not bring about an enduring peace and that the guns only fell silent for 21 short years before the world was plunged once more into unimaginable darkness.

Thankfully, it is testament to this country’s values and humanity, epitomised by the Archbishop of York’s prayer for peace in The Yorkshire Post today, that the passage of time has not lessened appreciation of the losses incurred in two world wars as well as more recent conflicts where Britain’s Armed Forces have been deployed.

Quite the opposite. Nearly a decade after Harry Patch, the last surviving veteran of the Great War, died, and as age wearily catches up with the dwindling number of soldiers, airmen and seamen who served in the Second World War, annual acts of remembrance continue to grow in size and stature because this generation knows that it is its collective duty to remember and pray that these painful lessons of history transcend those discernible political differences which do exist in these polarising times internationally.

To this day, Laurence Binyon’s poem, For The Fallen, transcends the ages and is even more pertinent as the savagery of the Great War is commemorated on a poignant weekend when the country stands still in thoughtful and respectful silence.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted;

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.