Relics of the Reich '“ how Germany is dealing with the buildings left by the Nazis

In reality most Germans are super-sensitive to any accusations of European domination and the country agonises over its Nazi past. Nazi architecture is one aspect of that legacy because, perhaps surprisingly to many people, much of it still exists and much has been put to new uses but generally only after much debate.

For example, the vast Prora-Rugen Nazi ‘Strength through Joy’ holiday camp, built as a sort of Nazi Butlin’s on the north German coast, is still there.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt remained unfinished in 1939 when war broke out and no one ever had a holiday there under the Nazis. For many years after the war, it was used as a military facility but now developers have acquired many of the blocks and are turning them into luxury holiday apartments.

More controversial is the debate currently under way in Nuremberg – home of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds built by Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, to stage the giant propaganda fests held annually during the Nazi era.

There is a museum on the site and much of the grounds have been repurposed for housing, sports facilities, an indoor arena and parkland. However, the iconic grandstand building, including Hitler’s podium, remains but is slowly crumbling.

Nuremberg has decided in principle to spend £60m to stop it falling down believing it to be an important historical building with a powerful story to tell about the horrors of the Nazi period.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhether it is right to use former Nazi buildings in these ways depends, in my view, on how closely the buildings were associated with the Third Reich’s terror machine.

The sites most associated with the genocide and terror are, of course, the concentration camps but also places like the Gestapo Headquarters and the Wannsee House in Berlin where senior Nazis met to decide on the ‘Final Solution’.

Of the estimated 15,000 camps established in all countries by the Nazis, many were destroyed either by the Germans themselves or by the Allies soon after the war.

Seventy years on, though, a significant number remain as memorials and museums. The original impetus to preserve them was, in most cases, as a result of pressure from victims and their families.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMore recently, however, that has changed and now most concentration camp memorials in Germany are supported financially by the Federal Government.

Many sites associated with the German war machine – the factories, the U-boat pens, the rocket launch sites– are still there.

Some remain in military use and some factories utilised for the war effort, such as the VW factory in Wolfsburg, survive but have been converted back to peaceful ends. Crucially, at VW Wolfsburg there is now acknowledgement of the suffering that occurred there principally through the use of forced labour.

Finally, there are those places specifically built by the Nazis as statements of their power and world view.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese include the sites built for the 1936 Olympics, airports in Berlin and Munich, the party headquarters in various cities and the private homes and grounds acquired or built for the Nazi High Command.

Most of the Olympic sites are still in use. Many Nazi administration buildings have been put to new uses. Although most homes of senior Nazis were demolished by the Allies, or later by the post-war German authorities, some do remain as private residences – including Albert Speer’s architectural studio.

My own experience of visiting many Nazi sites leaves me in no doubt that, overall, Germany is a country handling its difficult past seriously and with a degree of critical reflection.

The memorial sites are solemn and chilling and no-one who visits Dachau or other camps can fail to be impressed by the simple commemoration of multiple victims that these places now offer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdVisiting the museums in Nuremberg, Berchtesgaden, Berlin and elsewhere, did not leave me feeling that there was an attempt to explain away and exculpate.

Moreover, some of the buildings that have been kept like the Berlin Olympic Stadium are actually fine buildings which have, at least in part, outgrown their Nazi taint.

Above all, though, it remains vital that the story of how Germany became the Third Reich, and the ensuing catastrophe, is told for future generations.

The history of the buildings and spaces where that story unfolded is a crucial element in ensuring that this happens.

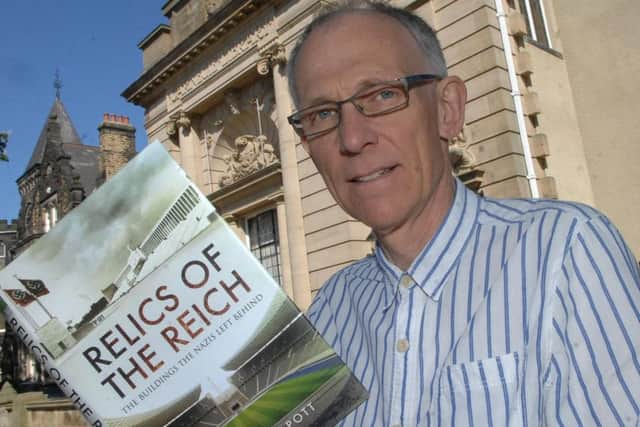

Colin Philpott’s new book Relics of the Reich, published by Pen and Sword, is priced £19.99 and available on http://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Relics-of-the-Reich-Hardback/p/11862