Sheffield's lost castle gives up its secrets

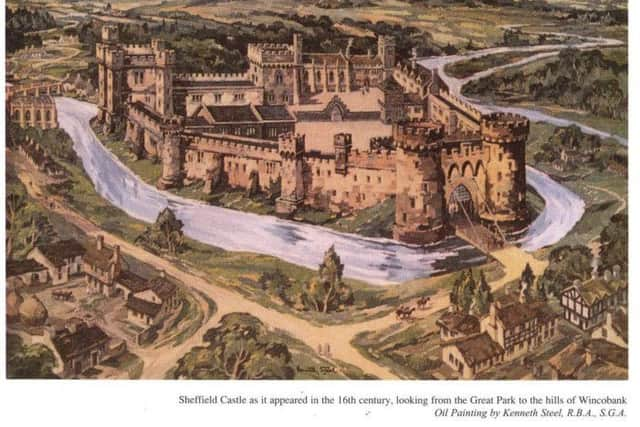

The formidable motte and bailey castle at the confluence of the Sheaf and the Don, which once dominated Sheffield city centre, held the former Scottish monarch for 14 years in the 16th century. But it was razed to the ground by order of parliament in the aftermath of the civil war, and eventually its remnants were buried by the shops and cafes of the concrete 1960s market hall the council named after it.

Today, however, it emerges that the castle had a greater impact on the development of the city than anyone had imagined.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdResearchers from Sheffield University have established that its creation was part of a detailed town plan whose streets form the core of the city centre today.

The Castlegate area, home to the former Sheffield Stock Exchange and the 18th century Old Town Hall, is the oldest part of the city but has become run down in recent decades. The demolition of the market two years ago and the promise of redevelopment has cleared the way for a wholesale excavation.

The diggers will not move in until May, but the process begins today with the publication of findings from excavations in the 1920s and 1950s which went largely unpublished at the time and are only now being pored over by historians.

Funded by a bequest from a former student, university archivists have established that the castle contained 11th and 12th century pottery from Lincolnshire, and a moat into which a cobbler dumped old, discarded shoes – some preserved examples of which shed light on the local footwear fashions of half a millennium ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProf John Moreland, who helped lead the research, said it was the medieval town plan, uncovered by his colleague Dr Gareth Dean, that was the most significant find.

“When the castle was laid out it done so in quite a planned way,” he said. “If you look at the layout of Sheffield now, you can see that the structure of some of the current roads reflect and respect the plan that was established for the castle.”

Its demolition, following its surrender in 1644 when it was briefly besieged, contributed to the gradual shift of the city centre to its present location, Dr Moreland said.

With no contemporary drawings or plans known to have survived, researchers have had to work from photographs taken in the 1920s, after the old abattoirs that dotted the area had gone and before the markets arrived.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome of the pictures, little seen until now, show walls 6m high and a warren of underground buildings in which Queen Mary could have been held prior to her execution.

Prof Moreland said: “Sheffield is known for steel production and its rich industrial heritage, but its roots lie in the middle ages. If not for its demolition following the Civil War, its skyline might still be dominated by its castle.”