Spanning centuries: Restoring keystones of the Yorkshire Dales landscape

Pete Roe reckons it’s as well he has a sense of humour in his work restoring what are officially known as “archaeological landscape features” in the Yorkshire Dales.

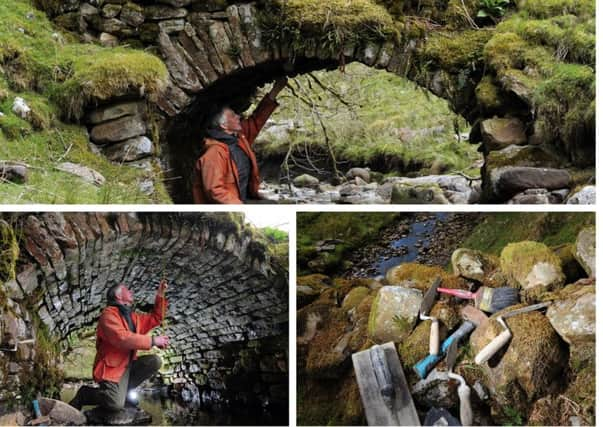

Rejuvenating packhorse bridges spanning bubbling gills that have long appeared on jigsaws and calendars is just one of his numerous freelance jobs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe also reconstructs ancient lime kilns that dot the landscape wherever there are limestone scars.

This specialist work presents this lanky 60-year-old with challenges, like the derelict lime kiln near Lady Anne Clifford’s Highway above Mallerstang that required his attention. “It was typical of the work I do,” Pete says over coffee in the Moorcock Inn, on the road from Sedbergh to Hawes.

“The kiln that nearly killed me,” he muses, stirring his brew. “The top had fallen off. The kiln resembled an egg-timer with one side collapsed.

“I was just starting work on the parapet and noticed a piece of rusty metal.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I hit it a few times with a lump hammer. Then got my biggest crowbar and prized it out. It dropped at my feet.

“Nine to ten inches long, it was pointy at one end and blunt at the other. Like a big bullet. I thought, ‘Whoops! That could go ‘bang’. I regretted hitting it quite so hard. The bomb disposal experts took it away. Aye, it went bang.”

According to a local farmer the Army brought special trains up to Garsdale in the 1940s. Bofors guns were mounted on low-loaders for anti-aircraft exercises. “A plane would tow a dummy aircraft on a mile-long wire above the dale.

“Trainees on board the train would practise shooting at this target. Well, one shell inadvertently hit the lime kiln.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“You wouldn’t want to be the pilot, would you?” he comments poker-faced.

Pete arrived in God’s Own County over 30 years ago from the Black Country, initially to run Keld’s YHA for five successful years.

Fortunately for the clients who rely on his craftsmanship, he left the hospitality business and followed his passion for restoring old structures, including his painstaking work rejuvenating lime kilns and packhorse bridges.

“It’s tough handling heavy stone blocks up there on the rain-battered uplands like Wensleydale, Swaledale, Arkengarthdale or upper Wharfedale,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThunder and lightning is always a risk. Forked lightning has zapped his metal spades, shovel and crowbars. He sat out one storm reclining in the “barrel” of a lime kiln while sipping Thermos coffee.

Working on an independent basis for the Yorkshire Dales National Park (YDNP) as a building conservation contractor, the crux of his labours is fettling arches that have collapsed, both in the barrel of the kilns and in the span of the old bridges.

Tricky. Especially as these arches were built without the use of mortar, just the pressure from adjacent stones next to other holding the curve into place. The barrel at each lime kiln’s entrance drew the draught to boost the mini furnace that roared inside.

It was in such kilns that builders baked the lime to make the mortar they required for dwellings and barns. Not forgetting the farmers who used kilns for producing quicklime. For centuries this was used as fertilizer on the land, thanks to the calcium oxide it contains.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are different theories on how the packhorse bridges originated. Some say, he tells me, they are medieval; others that the Romans built them to span the becks for which the Dales are famous.

Does the water attract midges? I ask. “Tell me about it,” he says.

“Little blighters, I’ve tried everything. If you’re hiking the Pennine Way and put something on to repel midges, that’s one thing.

“But if you’re continually working among them, the only real deterrent is to wear a midge net and gloves sticky taped to your sleeves.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne age-old packhorse bridge he restored is sandwiched between two buttresses of the giant 100ft Dent Viaduct on the Settle-Carlisle Railway.

The mini packhorse bridge was there first. The railway engineers built on either side and above it.

Problem was the arch was beginning to collapse and Pete had cut a large a hole in it to let him do the surgery required. Whenever goods trains rumbled overhead, the tiny bridge would tremble like a tuning fork.

“Basically, I dress stones roughly with a hammer then fit them side by side on top of a large plywood ‘former’ that I have built to support them from underneath.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I then hammer stone wedges in between any gaps so ensuring each stone is jammed into place. Just the pressure of the neighbouring stones against each other on the arch alone does the trick so they stay permanently in place.”

When he finally removes the bulky plywood-former from underneath the arch, there are invariably “clicking” noises that sound alarming. “No worries,” says Pete. “Those crunching sounds just means everything is settling into position.”

Embarrassing if everything collapses into the stream? I suggest.

“Indeed it is,” he says. He won’t be drawn other than to say none of his bridges have suffered this ignominious fate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYDNP Senior Historic Environment Officer Miles Johnson pays tribute to his work, saying, “Pete is a skilled conservation builder who has worked on a number of important heritage projects for the Park Authority over the years. It’s good to see him earning recognition for his building work.”

He has different strings to his bow, like his other fellow contractors who also work for the NPA, just one example being the re-roofing of a stone building in Dentdale for one of Cave Rescue Organisation’s members.

Besides completing many projects at England’s highest pub, the Tan Hill Inn (including entering the septic tank to repair walls), he also has a never ending tick list of work-in-progress from local farmers. One such recent task was to descend into a slurry pit covered with ice to retrieve a big propellor that stirs the slurry, and which had broken off. Now it is back at work.

“I usually work alone, but I’m never lonely,” he says. “I have my dog and if you can’t enjoy your own company, you’re a sad person.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a leading light in an upper Swaledale dramatic group his day job lets him mull over his lines for forthcoming plays. There’s nothing like working on a lime kiln or packhorse bridge, he says, for “taking you out of yourself”.

True to form, he lives in a farmstead 1,400ft above sea-level, above Gunnerside, near Reeth. The building was a ruin which he restored. His nearest neighbour is a mile away. Ghosts there are – of the lead miners who worked in Gunnerside Gill.

“What!” I exclaim, suddenly realising. “You have no grid electricity?”

“Mains electric is so passé,” he laughs. “Why do you want it? You don’t need it all. If I had it I’d only waste it. Gas lights and oil lamps do for me, and a nice big wood-burning stove. It’s very cosy.

“As long as I have a warm back and a full belly, what more can you ask?”