Thousands of rare 1920s and 30s dance band records are now on display in Huddersfield

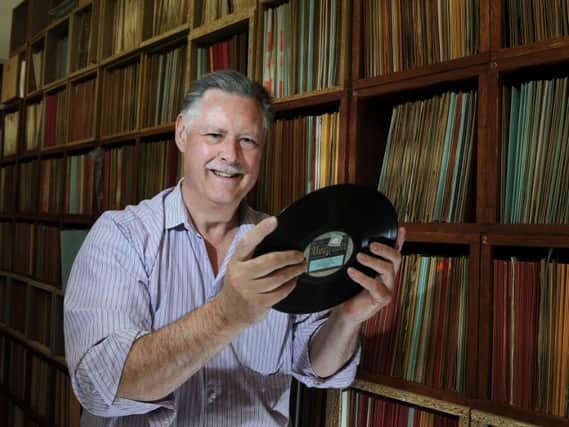

It’s the world of Make Yourself a Happiness Pie, of I’m Tickled Pink with a Blue-Eyed Baby and Every Single Little Tingle of my Heart... the world Charles Hippisley-Cox celebrates through his collection of 10,000 records.

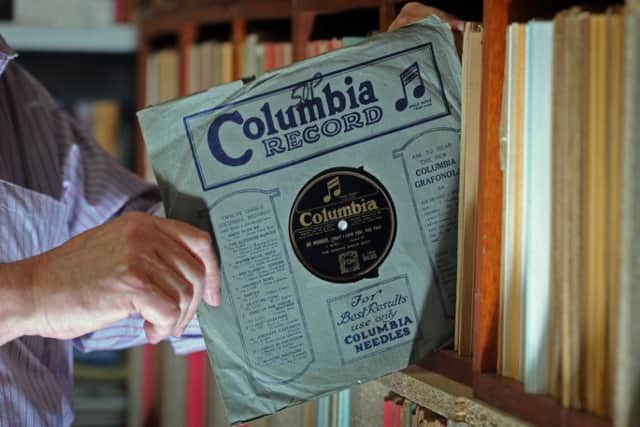

It’s probably the world’s leading collection of recordings from “the Golden Age of British dance bands” – almost entirely on 78s, those crazily spinning, dauntingly heavy, easily shattered shellac discs that held sway for the first half of last century. After being phased out in the 1950s, they could long be found stacked in dusty corners of junk shops (“You can use them as plant pots,” shop-owners would tell collectors, unhelpfully).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTen thousand records: that’s 20,000 three-minute sides, about (quick calculation) 1,000 hours of foxtrots, quicksteps and waltzes by Jack Hylton, Henry Hall, Roy Fox, Bert Ambrose and dozens of other stars from the Twenties, Thirties and Forties. A potential month and a half of non-stop, patent-leathered, silver-sling-backed dancing. Cocktails optional.

With an eye on posterity, Charles – not, by his own admission, as posh as his surname suggests – has deposited the collection with the University of Huddersfield, where he’s a senior lecturer in architecture. And now it’s gone public thanks to Heritage Quay, the university’s fascinating archive.

Play me one of them, I say. Charles scans the online catalogue and plumps for I’m for You a Hundred Per Cent, a foxtrot by Carroll Gibbons and the Savoy Hotel Orpheans; they were sometimes recorded as Carroll Gibbons and his Boy Friends, which could prompt all sorts of gender issues today.

Sarah Wickham, Huddersfield’s university’s archivist, taps a few keys on her computer and the record’s instrumental introduction floats round the archive centre: a lulling, easy rhythm, an embracingly warm atmosphere, a range of emotions as serenely smooth as the band’s mellow sound.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Two trumpets, trombone, three clarinets with sax doubling, a couple of violins,” says Charles, almost without thinking. “The pitch changes very shortly for the vocalist, Jack Plant, who sings in quite a high key...” Cue Jack Plant:“I’m for you a hundred per centIn a million little ways;I’ll be true a hundred per centAnd that’s a lot these days.”

The three of us are involuntarily smiling, immersed in a warm bath of nostalgia for a less strident musical age, relaxed and reassuring, that none of us actually remembers. As Charles says, it’s “the fantasy escapist world” of Pennies from Heaven, Dennis Potter’s poignant 1970s TV musical drama about a travelling salesman in which the action – set in the Thirties – often halted for the characters to express their inner yearnings by miming to dance band records just like this one.

Earlier, driving me over to Huddersfield from his home in Sheffield by a startlingly rural route, Charles explains his fascination for collecting what unbelievers might regard as quaintly period music designed for even quainter period technology.

“It started when I was at school,” he says as we pass Wigtwizzle. “I was caught up in Beatlemania and liked the pop music of the Sixties – but I didn’t like the music of the Seventies.” An alternative was lurking at the back of a cupboard at the family home in Birmingham. “There were some 78s there. I played them and they seemed a window onto a different world. So I must have been about ten or 11 when I started collecting.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first record he bought? “Amy, Wonderful Amy, by Harry Bidgood’s Studio Band on an eight-inch record on the Broadcast label; I bought it for sixpence.” Harry Bidgood? He recorded more memorably as Primo Scala and his Accordion Band.

Together with his cousin Mike Thomas, Charles was soon hooked on dance band music and was scouring junk shops for records. “It was an age of relentless slum clearance and the shops were piled high with 78s,” he says, as we pass the turn-off to Midhopestones. “You could get a rucksack of them every weekend.”

So while their schoolfriends were listening to Status Quo, Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd, Charles and Mike were absorbed in the likes of Happy Feet by Jay Wilbur and his Band, Button Up Your Overcoat by Percival Mackey’s Ever Bright Boys and A Bouquet for Cole Porter by Arthur Young and the Youngsters.

“The music was engaging, with a commitment to melody and musicianship. Arrangers were taking what was essentially an American kind of music and making it sound British. And it was the humour. British dance bands sound like a group of friends having a good time... and somebody happened to record them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“By 1974, we had 4,000 or 5,000 records each, enough to dominate a bedroom... which is not very healthy for a teenager. We realised that we couldn’t just buy anything at random.”We speed through Crow Edge and Charles reflects: “When you’re a collector, it’s the thrill of the object, the thrill of the chase. You might get a batch of test pressings turning up in a barn in Dorset...” Can it get obsessive? “I prefer the word ‘focus’.”

Inevitably as a fully focused collector, Charles started seeking out rarities – test pressings, factory pressings, alternative takes, sometimes buying up records from other collections at £30 to £40 a time (“though most of the stuff I’ve bought has cost less than £1”). And so, as his bedroom floor sagged, an archive evolved.

“From the 1990s I took up the challenge of making my collection the definitive one,” he says just past Brockholes on the final run into Huddersfield. “The BBC archives have only kept examples of highbrow stuff on 78s. They were real cultural snobs. And some of the records in my collection are beyond value because they would have been the only copies.”

But where some early jazz records became collector’s items, dance band records were generally forgotten when foxtrots and quicksteps were swept away by Swing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnxious to avoid his collection ultimately being dumped in skips (a frequent fate of 78s), he suggested to Sarah Wickham that it could be housed at Heritage Quay. She agreed, but with a major proviso: that he would make digital transfers of every record.

“As a curator, you don’t take 20,000 things without the means to make them accessible,” she says. “What people generally want to do is listen to the music. I don’t remember anybody actually being interested in the records as artefacts; people are interested in vinyl as a concept but not 78s.”

It took Charles eight years to make the digital transfers. “I spent every spare moment of my time making them – a really long process that has driven people mad,” he says. Each transfer took around 20 minutes, removing clicks and pops with a computer, fading in at the start and out at the end.

“There’s not a lot of filtering and fiddling around like you sometimes get with CDs, adding echo or ambience,” he adds. He mentions using “truncated elliptical styli”, which I feel I should make a note of.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo here at the sleek, elegant archive – which we agree creates the unexpected but pleasant impression of being on an ocean liner – the collection can be accessed via the transfers. It shares space with another half-million items from 100 collections featuring Rugby League, Ted Hughes, Huddersfield’s Asian Voices oral history project, the nationally important British Music Collection, Bamforth’s postcards and Huddersfield Amateur Light Opera Society. If you’ve ever longed to pore over the Colne Valley Labour Party archive or work your way through a full set of Wisden, the cricket lover’s bible, this is the place for you.

The 78s are stacked in orderly fashion in a cabinet 12ft long and 10ft high (“the first time all the collection has been together” says Charles). He reaches down a record in a brown paper sleeve: a test pressing, he says. Previous owners have scribbled notes on the sleeve. “That was written by Johnny Wadley,” he says. “And that’s Dave Bennett’s writing. Probably only half a dozen of us have that sort of detailed knowledge. All the old-timers have gone.”

Does he feel a sense of loss at being separated from his collection? “It gives us back a room at home. And to find somewhere where the collection can rest is a relief and a reassurance.” Sarah jumps quickly in: “I don’t want a collection that ‘rests’,” she says. “I’m in the business of looking after heritage, but I have to be very careful what we accept. It has to earn its keep. I’m not in the business of helping people with their house clearances.”

But what, I ask Charles, about the ritual aspect of playing 78s, the careful lowering of the needle or stylus, the gentle “frying sausages” crackle of surface noise? “Listening to a digital download isn’t quite the same thing, I’ll admit that,” he says. “But the sound is still very evocative.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt certainly is on I’m for You a Hundred Per Cent, one of his late mother’s favourites, he says. Harnessing new technology in the service of old music, he has posted it on YouTube. It’s illustrated by black and white snapshots of her seaside family holidays in the Twenties and Thirties... paddling and laughing and larking on the sands. It’s very touching.

Heritage Quay: 01484 473168; www.heritagequay.org