Health crisis - Are we facing an antibiotic apocalypse?

As warnings go, they don’t get much starker than the doom-laden one issued by the Director-General of the World Health Organisation (WHO) last week.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said that antimicrobial resistance was a “global health emergency that will seriously jeopardise progress in modern medicine.” He went on to say, “there is an urgent need for more investment in research and development for antibiotic-resistant infections including TB, otherwise we will be forced back to a time when people feared common infections and risked their lives from minor surgery.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Ghebreyesus was speaking following the publication of a WHO study highlighting the shortage of new drugs in the pipeline needed to combat the growing threat of antibiotic resistance.

Alarming as it is, we’ve been here before. In 2013, England’s Chief Medical Officer Dame Sally Davies described the growing resistance to antibiotics as a “ticking time bomb” and said the danger should be ranked alongside terrorism and global warming on a list of threats to the nation.

The following year David Cameron warned that the world could soon be “cast back into the dark ages of medicine” unless action was taken to tackle this threat.

However, the latest warning from the WHO has once again raised the spectre of a future where a simple cut to your finger could be potentially fatal. It would mean basic operations, like getting your appendix removed or having a knee replacement, would suddenly be dangerous, while cancer treatments and organ transplants could kill you. We aren’t yet facing such a nightmare scenario, but the day when we might do is getting closer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

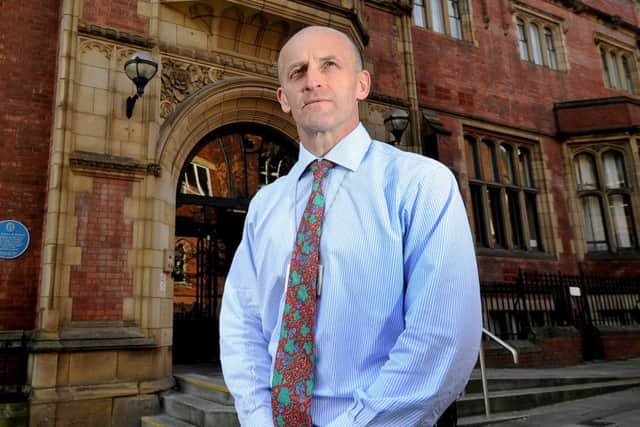

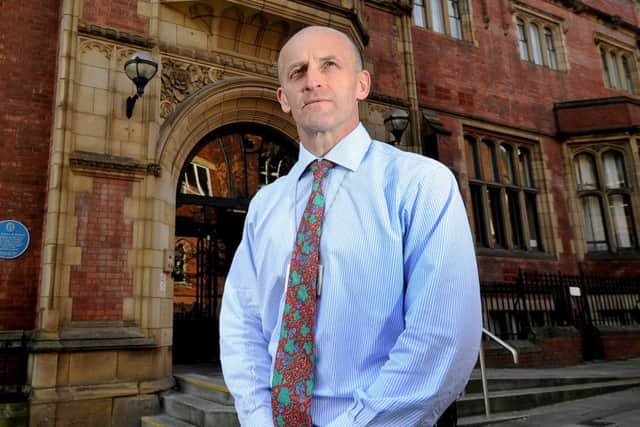

Hide AdProfessor Mark Wilcox, Head Of Research and Development Microbiology at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, says fears of a potential global health emergency aren’t exaggerated. “We’ve been very slow in recognising what’s round the corner and what, in some cases, is already here.

“We are now regularly seeing some untreatable infections in some countries. Here in the UK that’s uncommon but nevertheless it is still happening and that didn’t happen five years ago.”

There are around 60 antibiotics that a doctor can prescribe on the NHS which until now have been able to deal with the infections we encounter. The problem is it doesn’t take much for some bugs to alter so they are no longer susceptible to existing antibiotics.

“We’ve got closer and closer to the cliff edge and now unfortunately sometimes we’ve gone over the cliff edge, so it is a real crisis. Are masses of people dying from untreatable infections? No, not at the moment, but because of that cliff edge it could well get to that stage. Especially when you think it takes 10 years to go from a bright idea to an antibiotic that a doctor can prescribe. That’s a long time for the situation to get worse.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the main problems is there aren’t enough new antibiotics being produced.

“We went through golden period from the 1960s through to the 80s when we came up with genuinely novel antibiotics, as opposed to a near relative of previous ones.

“But if you’re a drug company and you have a choice between developing a new arthritis drug which a patient will potentially take every day for the remainder of their life, or a new antibiotic which someone may take once over the course of seven days, the economics say which one you’re going to put your efforts and investment into.”

Another major concern is our over-reliance on antibiotics. “It’s an absolute given that if you use antibiotics the resistance will develop sooner or later. Yet there’s still this attitude that antibiotics don’t have any risk and that it’s better to take them than not to take them. But we’re now reaping the downsides of this,” says Prof Wilcox.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Four out of five prescriptions that are written out for antibiotics are done on a best guess basis. In other words the doctor doesn’t know exactly what the bug is when they’re prescribing the antibiotic.

“In some instances the antibiotic might be wrong and in some cases they’re not needed at all and in most cases that’s because it’s a virus causing the infection rather than bacteria.”

Prof Wilcox says the situation would be helped by GPs having access to diagnostic tests they could carry out quickly when patients come to see them.

Last year the University of Leeds was awarded over £3m by the Medical Research Council to develop such a test – something Prof Wilcox has been involved with. “If doctors had an accurate test result in front of them it would stop some of the prescribing that’s going on unnecessarily,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“At the moment there are some untreatable infections. They’re rare in the UK, they’re much more common in countries like Greece, Italy and Israel. These tend to affect patients with complex problems, people who’ve had transplants or cancer.”

At present this isn’t affecting people going in for routine operations, but the fear is it could spread. “The doomsday scenario is they start spreading,” he says. “That largely hasn’t happened yet but it could start to, and unfortunately the building blocks are in place for that to possibly happen.”

Which is why there must be renewed focus on developing antibiotics. This can take the best part of a decade and Prof Wilcox says the burden of costs needs to be shared between healthcare organisations, governments and pharmaceutical firms. “It needs to be shared because this is a problem for society, it’s not just a problem for hospitals or pharmaceutical firms, it affects all of us.”

Dr Emma Boldock, a clinical microbiologist and a lecturer at the University of Sheffield, agrees that there needs to be greater collaboration to help tackle the problem. “The bacteria are usually one step ahead of us and if we’re throwing the same old antibiotics at them they just become resistant and go on and spread,” she says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhich is why more research and investment is urgently needed. “We can’t bring these drugs to the market on our own, we need fruitful partnerships and I think this is only just being realised as the best way forward,” she says.

Researchers and scientists at the University of Sheffield’s Florey Institute are working on the front line of this battle to tackle what is one of the world’s biggest biomedical challenges. “We’re a unique institution investigating antimicrobial resistance and we’re in a great position to be a national leader and a world leader in this area,” says Dr Boldock.

Not that she’s downplaying the scale of the challenge that lies ahead. “This won’t be solved easily. The problem isn’t going to go away and it’s probably going to get worse before it gets better.”

Dealing with a health emergency

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has warned that the world is running out of antibiotics.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAntimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs naturally over time, but other factors have helped to accelerate the process such as the “misuse and overuse” of antimicrobial drugs.

AMR is threatening the ability to treat common infectious diseases. Around 700,000 people around the world die each year due to drug-resistant infections.

Experts have estimated that by 2050, 10 million lives could be lost every year as a result of drug-resistant infections. If antibiotics lose their effectiveness then key medical procedures – such as caesarean sections and joint replacements – could become too dangerous to perform.