Unique member of Leeds Pals inspires new book about Indian contribution to WW1

Thirteen years ago, academic and author Dr Santanu Das came across a shattered pair of spectacles on display in an Indian museum which belonged to a lone non-white soldier among Yorkshire volunteers fighting on the Western Front as part of the Leeds Pals.

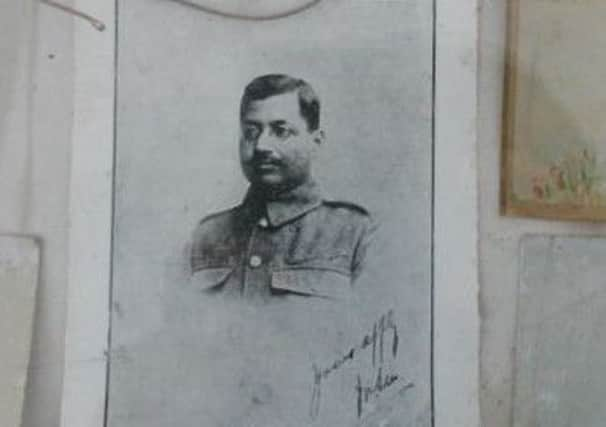

The story of Jogendra ‘Jon’ Sen, a highly-educated Bengali who completed an electrical engineering degree at the University of Leeds in 1913 before signing up to the 1st Leeds “Pals” Battalion and being killed in action near the Somme in 1916, was the inspiration for a major new book by Das about India’s extensive involvement in World War I as part of the British Empire following over a decade of research that has taken him across the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis task was extensive; more than one million Indians fought overseas during the war and almost 70,000 were killed, while many of those involved - unlike their European counterparts - did not keep diaries or write letters about their experiences on the frontline.

The resulting book, India, Empire, and First World War Culture: Writings, Images, and Songs, focuses on the human stories of Indian soldiers and their families caught up in the conflict; starting with the story of Jon Sen.

Das saw Sen’s glasses, shattered and smudged with blood, for the first time in a museum in the soldier’s home town of Chandernagore, a former French colony near Kolkata - the city where the author himself grew up before coming to England. The display identified Sen as a private who had served in the West Yorkshire Regiment.

“I saw these bloodstained glasses and was struck by the poignancy and fragility of the glasses, the fact they were largely intact and this man had worn them in the battlefields of France,” says Das, who is a professor of English literature at King’s College London, says. “Those glasses were all his mother got back when he died. My first book was on World War One and I had become quite surprised and troubled by the complete inattention towards the contribution of Indian soldiers.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSen’s story stayed with him and he mentioned it several years later when giving a talk at the University of Leeds. An audience member said Sen had been a student at the university, and his name appeared at the university’s war memorial.

This in turn led to a university research project to find out more details about Sen. It transpired he had volunteered for the Leeds Pals in the early months of the war, having recently gained a degree in engineering.

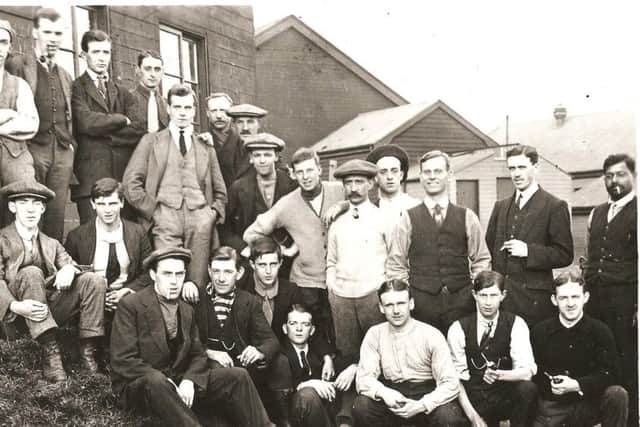

Sen, believed to be the only non-white member of the West Yorkshire regiment, had hoped to become an officer but the racial politics of the time meant he did not progress beyond being a private. Arthur Dalby, one of the soldiers who served alongside him, remembered Sen as “the best-educated man” in the battalion. “He spoke about seven languages but he was never allowed to be even a lance corporal because in those days they would never let a coloured fellow be over a white man,” Dalby said.

Killed in action in May 1916, aged 28, Sen is believed to have been the first Bengali to have died in the war and his death was widely reported in the UK at the time. Das says: “There is now amnesia about the Indian contribution to the war but at the time, people were interested in Jon Sen’s story. His death was reported in The Times and The Yorkshire Evening Post.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Evening Post story published on June 2, 1916, ran under the headline ‘Leeds ‘Pals’ Lose An Indian Comrade’. But, as the book explains, the sacrifices of Indian soldiers like Sen for the Allied war effort have been largely brushed under the carpet both in the UK and India for different reasons in the decades that have followed.

“Across the world, from names emblazoned on the Menin Gate at Ypres to commemorative plaques at the Haydarpasha English Cemetery in Istanbul or the Taveta ‘Indian’ Cemetery in Kenya to memorials scattered across South Asia, one finds recognition, in varying scale, of the Indian contribution,” the book says. “But a general amnesia soon set in: as Europe started recovering from its wreckage, its thoughts naturally turned to its own dead, mutilated and bereaved. Meanwhile, in post-war India, the nationalist movement gathered momentum under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, and, in this heated atmosphere, there was little scope for remembrance. No narrative space was created, at the national or public level, around the country’s war casualties or veterans.”

Das says the war had been supported by India’s political parties who hoped the nation would be rewarded by greater political freedom. But this feeling began to change after the war ended and no improvements followed - and was compounded by the Amritsar massacre of April 1919 when British troops killed hundreds of Indians peacefully protesting against the arrest and deportation of two national leaders.

Das says while those in India who had hoped its involvement in the war would lead to change suffered “an enormous amount of disillusionment and despair” at British attitudes after the end of the conflict, for many of the ordinary soldiers on the frontline such political questions were not at the forefronts of their minds during the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Throughout the 19th Century, Indian soldiers had been sent to Egypt, Somilaland and China during the Boxer rebellion,” he says. “For many, soldiering was a means of a livelihood, not ‘we are fighting to get freedom’.”

One of the challenges of his research was getting hold of first-hand accounts, given many soldiers did not read or write. A major discovery was hundreds of recordings of Indian prisoners-of-war who had been kept by the Germans in a camp close to Berlin. Such oral archives became key to his research, along with speaking to the families of Indians who had served in the conflict.

“Writing the book, I thought I would be done in 18 months but I started to realise the vastness of the material,” he says. “I realised I had to look at objects and photographs and approach this whole thing sideways as they didn’t leave behind letters and diaries. I didn’t want to write a military history but rather examine ‘how did these men feel, what did their wives and children experience’? I thought it is amazing this story has been forgotten, not just in Europe but in India. I wanted to tell the stories of the soldiers’ experiences. What I want to come across is the emotion and feelings of these men who went to different parts of the world and how complex World War One was for South Asia, while challenging the perception of it as a ‘European war’.”