What rugby league in Batley tells us about Brexit

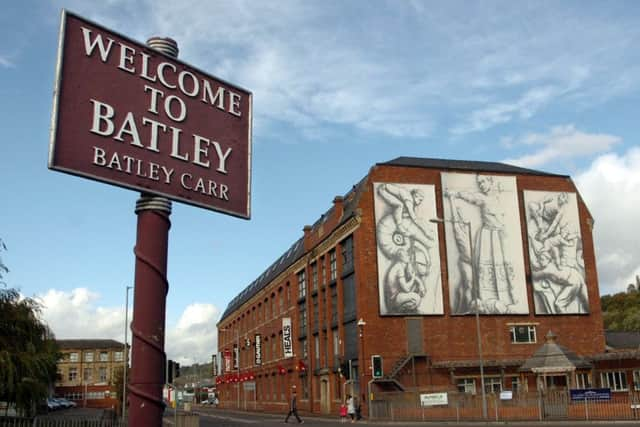

The good things about life in Batley, says Janet Virr, are its “magnificent buildings, the pride and the heritage is wonderful – and there’s a fantastic rugby league team.” The retired primary school headteacher spins around to proudly show off her Batley Bulldogs rucksack.

The club is at the heart of the community, though it “needs more supporters,” Virr admits. In truth, it feels like the rest of Batley and the Heavy Woollen District – a cluster of West Yorkshire towns that took its name from the local cloth manufacturing industry that has all but vanished – needs more backing, too. “Unfortunately, there is a downside in the shopping areas,” she concedes. We’re standing next to the town’s marketplace, and its clear what she means. It’s an attractive space, surrounded by a civic trinity of Victorian town hall, Carnegie library and Methodist church, but today it’s hosting just two lonely stalls.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWalking down Commercial Street, we pass a charity shop, an Admiral Casino, a vacant unit, a Pound Express and a William Hill betting shop, with a Coral bookmakers opposite – hardly a vibrant high street. The biggest store on the road by far is the Tesco Extra, which opened in 2003. “The market used to be full,” says Peter Richardson, 58, “but Tesco sucked everything out.”

There is a thriving local history society, but more of Batley is gradually being consigned to the memories and nostalgia of their discussions. The Batley Variety Club, which once hosted stars such as Louis Armstrong and Roy Orbison, closed in 2016. The local police station, which is now empty, was put up for sale last year, with West Yorkshire Police blaming “sustained austerity”.

“The majority of the public areas are run by volunteers,” says Virr, 64, who successfully fought with friends to keep their local library open.

Batley, a town with a population just under 40,000, is the kind of place that researchers at the centre-right thinktank Onward had in mind when it published a report in October, just before the start of the general election campaign. It urged the Conservatives to target “rugby league towns”, a group of traditionally Labour seats in the north of England, for their high numbers of “Workington Man” voters – older, Brexit-backing, working-class men who prioritise “security and belonging” rather than freedom in social and economic policy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring a Tory election celebration this month, cabinet minister Michael Gove credited Onward and its report with a “starring role” in helping deliver the election win. Nineteen of the 20 target seats identified by Onward turned from Labour to Tory, including several rugby league towns: Wakefield, Warrington South, Keighley, Barrow, Dewsbury and, of course, Workington.

The constituency of Batley and Spen – represented by the Remain-supporting Labour MP Jo Cox until she was murdered by a right-wing extremist in nearby Birstall during the Brexit referendum campaign – wasn’t on that list. It was regarded as too long a shot.

Yet even here, Labour’s majority was cut from around 9,000 to 3,500 votes last month – and that was with a pro-Brexit independent group taking 6,000 votes which it’s reasonable to expect would otherwise have gone to the Conservatives.

Many voters in the town, which is thought to have voted 60:40 for Brexit, will be glad to see the UK finally leave the EU tomorrow night, and Batley is a place that illustrates the demographic and economic factors shaping life in rugby league towns and thus changing the country’s electoral landscape.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a sport with a deeply anti-establishment heritage, the rugby league link between those 20 towns is important. It’s a game that began as a revolt, created in 1895 when clubs from industrial Lancashire and Yorkshire split from the public-school men who ran rugby union.

Resentment of the English rugby union establishment – centred on London and closely connected to fee-paying schools – remains strong among the game’s supporters, as does anger over the game’s neglect by the London-centred national media.

The new season starts tonight with a Super League match between Wigan and Warrington, but Batley won’t be competing with them in the coming months. Though the club’s past glories include winning the first Challenge Cup in 1897, earning them their nickname “the Gallant Youths”, these days they reside in the second tier, with attendances averaging around 1,300.

Tony Hannan, co-editor of rugby league magazine Forty20, spent a year with Batley Bulldogs for his book Underdogs. It was written in 2016, the year of the EU referendum.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHannan says rugby league is “about community” for its supporters, with none of the social cachet that accompanies watching rugby union. That identity will be on show when Batley fans reconvene for the first game of the season against Featherstone Rovers on Sunday.

People who watch rugby league in Batley are there because they “love the club and the sport,” says Hannan. “Batley are a family club in the real sense of the word, in that everybody there seems to be related to each other, or part of some extended family.”

Everywhere around the Mount Pleasant ground – officially known as Fox’s Biscuits Stadium, owing to sponsorship from the big local employer – little plates can be seen with the names of fans who are no longer around to watch. “It’s a very meaningful thing,” says Hannan.

The “whole culture surrounding the game” reveals much about national politics, he argues. While many were surprised by the Brexit vote and nature of the Tory election win years later, “if you’ve been knocking round in rugby league circles – which is still, despite the game’s best efforts, very much a working-class, northern concern in this country – you probably wouldn’t have been quite so surprised,” he adds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMuch of this has to do with the decline of towns. Batley is only 15 minutes’ train ride from the thriving centre of Leeds, the only big-city club in rugby league, but its economy is in a different world.

Walking further along Commercial Street are Rachel and Kevin, in their early 30s. Rachel says there’s “nowt for people to do” in Batley. What’s good about it? “Tesco’s,” she replies “That’s it.”

Kevin, who works at the Fox’s Biscuits, is wearing a baseball cap and restraining a small yappy dog from launching at a bigger canine. He feels the town has “gone downhill in the last 10 years. The sense of community has gone.”

Batley’s “golden mile” has faded with the closure of pubs and variety clubs, he complains. “Do you ever watch Sky Sports?” Kevin asks, fondly recalling the time when presenter Jeff Stelling “called Batley the Las Vegas of Yorkshire” on air.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne mother walking with her son says that “the town centre feels downgraded.” What’s to blame? “Tory party policies,” she says. “There’s lots of homeless, lots of crime. It’s not even safe for children to walk on their own.” What would make things better? “Investing in the place – it’s because of cuts,” she replies.

If many people still blame the Tories, why has Labour suffered?

Will Jennings, a University of Southampton politics professor and a co-founder of the Centre for Towns alongside the Labour leadership contender Lisa Nandy, suggests that “in some ways, Labour’s problem is a towns problem”.

He explains that deindustrialised towns have ageing populations, a demographic the party is struggling to reach. Plus, with education replacing class as the key determinant of voting behaviour, the non-graduates prevalent in deindustrialised towns are shifting away from Labour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYoung people moving away to towns and cities with universities is one factor explaining why Batley saw its population of 16 to 24-year-olds shrink by 5 per cent between 1991 and 2011, while its population of over 65s grew by 35 per cent, according to a data tool from the Centre for Towns.

Tracy Brabin, a Batley-born former Coronation Street actress who became Cox’s successor as the local MP, argues that Onward’s rugby league towns analysis was an easy way “for southern thinktanks to patronise us in the north – they don’t understand my community and I won’t be told by southerners what my community is”.

The area’s problems centre on dismal transport links and the fact that “our communities have been absolutely under siege because of 10 years of austerity,” says Brabin, who is backing Sir Keir Starmer for the Labour leadership. Yet she also recalls conversations with people from working families “stood in the foodbank talking to me and [saying], ‘I’m going to vote Tory for change’.”

Have the policies of previous Conservative governments – deindustrialisation and austerity – been huge factors in the economic struggles of the rugby league towns?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWill Tanner, Onward director, co-author of its pre-election report and a former adviser to Theresa May in No 10, rejects this. “Governments of all stripes have pursued deindustrialisation since the 1980s,” he says. Tanner argues that the current political mood is a turn against “economic liberalism, not conservatism”, and the way such policies have “benefitted some places much more than others”.

He thinks that rugby league’s anti-establishment heritage was “relevant” to Tory election success. The Conservatives’ election slogan “was anti-establishment – getting Brexit done against the odds, in spite of a broken Parliament… It is hardly surprising that message resonated in rugby league towns,” he adds.

The uncertain future of rugby league as a sport also reflects the nation’s politics: the game is financially constrained because its base is in deindustrialised and deprived towns. It wants to expand into new markets in North America, yet preserving the traditional identity that has sustained it for 125 years is a challenge in itself.

Brabin, who wants to “amplify the brilliance of league” in her new role as shadow secretary of state for digital, culture, media and sport, points out that life in towns can bring “a sense of pride in your community, a sense of identity” as well as challenges.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNext to Batley’s empty market square, Virr praises Batley Bulldogs for their work getting women and girls playing rugby league and seeking to bring the town’s large Asian community into the sport. But she worries that “the age profile is going up” among Batley supporters and that “the game we love is not what other people want these days”.

Rugby league is sometimes caricatured as old-fashioned. But in terms of what it reveals about the impacts of deindustrialisation, globalisation, austerity and regional inequality on our national life, it is England’s most modern sport.

Batley and Spen: facts and figures

The House of Commons library ranked the 533 English constituencies for their deprivation last year. Batley and Spen was the fourth biggest mover in the wrong direction since 2015.

Only small remnants of the traditional cloth-making industry remain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut still 19 per cent of employees work in manufacturing against a national average of eight per cent, according to Office for National Statistics figures.

The proportion of employees in retail jobs (21 per cent) is above the national average (15 per cent).

Just 23 per cent of employees have a degree-level qualification or above, below the national average of 39 per cent.