Bygones: Fred Trueman emerged from shadow of the pit to join game's legends

Today would have been the great man’s birthday, as good a flimsy excuse as any.

According to Fred, “south Yorkshire was as white as the county’s rose” when he was born on February 6, 1931.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“My father ran out of the house to fetch the doctor,” he recalled in Ball of Fire, his 1976 autobiography.

“But I was too fast even then for most people.

“It was the usual run-up, you know – a rhythmical approach and straight through.

“By the time the doctor arrived, I was already born, all 14lb 1oz of me.

“My grandmother Stimpson, whose maiden name was Sewards, had delivered me, which put her in a strong position when they decided what to call me.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“So, I was launched into the world as Frederick Sewards Trueman.”

FST was born at No 5 Scotch Springs, Stainton, a row of 12 miners’ cottages on the edge of Maltby Main pit yard.

His father, Dick, worked at the pit, and Fred was the fourth of seven children.

The cottages were situated about half-a-mile from Stainton village, and roughly eight miles south of Doncaster and eight miles east of Rotherham.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHad Trueman been born approximately four miles further south – not the 300 yards of popular myth – he would have been a Nottinghamshire citizen and thus unable to represent Yorkshire.

When I wrote a book about Trueman a few years back (available in all good bookshops, incidentally, and plenty of bad ones, too, as the rubbish joke goes), I took a trip to South Yorkshire to seek out his birthplace.

It was no easy task, for the cottages were buried beneath landfill in the 1970s when the Maltby Main tip pushed up on their doorstep, and there is not the faintest trace of them now.

I enlisted the kind help of Sidney Fielden, the former Yorkshire CCC public relations chairman, who is familiar with that geographical area, and Ron Buck, a childhood friend of Trueman, and was thus able to get a striking sense of what the former fast bowler came up from in life.

To say that it took me by surprise is an understatement.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHitherto, I had read only what Trueman himself had written of where he was born 86 years ago today.

In his final autobiography, published in 2004, he related how “tender wild mushrooms, their gills tickled pink, were strewn across the meadows like miniature white parasols”.

He told how “many was the time as a boy I saw purple and buttercup-yellow crocuses catching the first flakes of a snowfall in their orange hearts before closing, stiff and tight, imperishable and unearthly like plastic flowers”.

He recalled “the clap of the wings of wood pigeon, the squawk of blackbirds and scuttling rabbits”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd he remembered long-ago Aprils when “the petals of tulips were scattered across the still cold soil like colourful casino chips”.

It was a wonderfully idyllic picture, and even accounting for the artistic skill of Trueman’s ghost-writer, I imagined Scotch Springs to be like something out of Last Of The Summer Wine.

The reality, however, proved somewhat different.

One winter’s afternoon, I stood with Sidney Fielden and Ron Buck staring out across an area of desolate wasteland in the imposing shadow of the Maltby Main colliery.

We looked at a filthy slurry pit close to mounds of landfill, where dirty black water gurgled and gargled, and a scene that was filled with a hopeless air.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“That’s where Scotch Springs was,” pointed Ron Buck towards an area in the wasteland, his voice quivering with pride and emotion.

Confirming that the landscape had changed little since the 1930s, he added: “People don’t realise what a climb it was, how far Fred came in life, as well as in cricket.”

Having stood there that day in the shadow of the pit, it was easy to see why Trueman developed what might be termed a romantic view of that south Yorkshire setting – a world away, indeed, from his final resting place at the beautiful Bolton Abbey in the Yorkshire Dales.

With the help of others, I was soon able to establish that this was a man who had to fight for everything in life – first of all for acceptance in a local area in which acceptance was not always readily conferred on those who lived on the edge of a pit yard, and then for acceptance in the still class-conscious world of English cricket just after the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOften, I have reflected on the moving juxtaposition of white snowflakes falling on the black apparatus of the coal field on the night that Trueman came into the world.

Indeed, the combination of snowfall and the soot-ridden surroundings somehow captures the contrasts and extremes of Trueman’s life.

And what a life…

The new-born baby who was too fast for the local doctor was certainly too fast for batsmen the world over during a remarkable career.

In the 20 years from 1949, Trueman captured 2,304 first-class wickets at 18.29 – the most by a bowler of genuine pace.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1964, he became the first man to take 300 Tests wickets, and it would have been 400-plus had he not been in-and-out of the England side, so often a victim of imagined wrongdoing.

If Trueman had been guilty of all the things that he was accused of, he would have had the knack of being in several places at once, his bad-boy reputation spiralling to Jack and the Beanstalk proportions.

Trueman, who passed away in July, 2006, was certainly not whiter than Scotch Springs on the night of his birth, but nor was he the sort of bad lad that he was often made out to be.

Tales of his drinking were largely apocryphal, although he was not averse to milking the popular image of a man who could destroy opponents one minute, celebrate with ten pints the next, and still find plenty of time for England’s female population.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

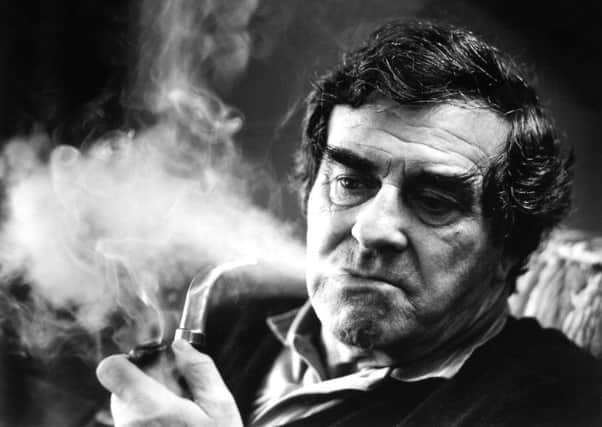

Hide AdWith his classical action and unruly mop of jet-black hair, Trueman was the epitome of a theatrical performer.

Certainly there have been few more humorous characters in any sport; there are so many “Truemanisms”, indeed, that one could easily fill an entire copy of The Yorkshire Post with examples of his repartee – and still have a fair few left over.

February 6 will thus forever be a significant day in the history of Yorkshire and England cricket.

In 1931, it was a day when the heavens not only dispensed snowfall on south Yorkshire, but also more than a healthy sprinkling of stardust.