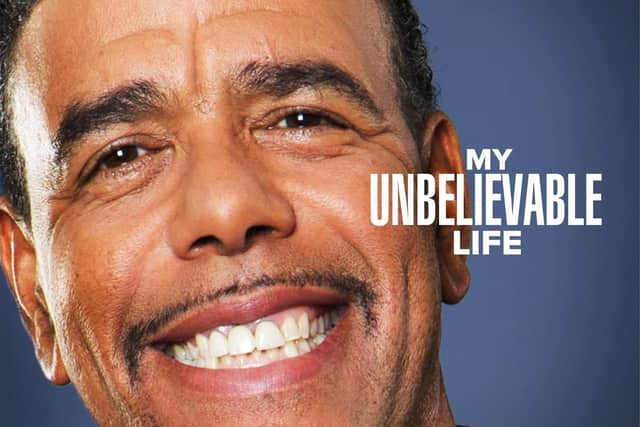

Chris Kamara interview: Fears football gave me dementia made me consider suicide but now I'm back on track

The Teessider is talking about the launch of his book, Kammy, which is about far more than making a few quid for someone who played for Middlesbrough, Leeds United and Sheffield United amongst others, ticking off a lifelong ambition with the first, a dream with the second.

"It was really important I wrote it," he says, going strong in his sixth Zoom interview of the day. "I was stupidly ashamed of my condition in the beginning so I'd like to apologise to every single person who has a speech problem or neurological problem.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I didn't handle things well. I felt as if it wasn't me any more and I couldn't continue. I want to put the record straight and raise awareness.

"Mentally it was challenging because of my under-active thyroid, it plays with your hormones (he laughs, nervously) so I get upset more than I ever used to. it's quite emotional, the book, but I had lots of help along the way so that was good."

The book certainly does raise awareness, its narrative flitting between the story of his time in football and his struggle with the condition which could have ruined his second career, as a bubbly television personality.

Acquired apraxia of speech is a motor-speech disorder that makes sufferers unable to control the muscles used to form words. For anyone it must be a horrible thing to live with, but for Kamara, 66 on Christmas Day, even more so.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen playing came to an end and management did not quite take his fancy despite enjoying his first job at Bradford City, verbal communication paid the bills. Kamara's over-excitable machine-gun delivery, punctuated by bellows of laughter, was his stock in trade and the affection the British public had for it allowed his TV work to branch out beyond football programmes like Sky’s Soccer Saturday and Goals on Sunday.

When that was not taken away but slowed down to the point he feared it might be, Kamara considered ending it all, like his former Leeds team-mate Gary Speed had under different circumstances in 2011, but mercifully only briefly. Now he has come to terms with his new reality it has opened the door to many friends – some of whom he has never met – to help him through.

I ask him if, three years on from his first symptoms, he is learning to manage his apraxia.

"I'm doing more than that, I'm getting better," he replies. "Since I've been to Mexico for treatment I'm improving all the time so instead of the connection between brain and mouth stumbling, I can actually put sentences together with fluidity."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRohit Kulkarni, a doctor based in Wales, got in touch when Kamara went public with his problem to tell him about a groundbreaking treatment he was involved in which could possibly reverse the condition. After five months of trying alternatives and persuasion from television presenter Kate Garraway whose husband used it to ease his crippling long Covid, Kamara took up the offer, leading to 28 hour-long treatment sessions in Mexico whose effect gave him a huge confidence boost.

But when his problems with balance and speech first became apparent – not just to Kamara but more alarmingly for him to Sky viewers – he was understandably worried. He is, after all, living in an era when awareness and deaths of footballers of his generation and older from dementia are on the increase. The list of known victims is depressingly long and probably only the tip of the iceberg but this year it claimed Gordon McQueen, a defensive lynchpin of the Leeds team a teenage Kamara worshipped.

"I used to know Gordon well," he says. "I worked with him on Sky. When someone close to you suffers from that, you think, 'Oh crikey!' It's no coincidence now the number of (former) footballers suffering from it. You try to think back to the time you had head injuries and stuff like that but thankfully all the scans I've had have disproved that – they're clear, I'm clear and my mind is clear now.

"I thought I had dementia or Alzheimer's so it's so difficult to think that in a few years' time I wouldn't recognise my family and I'd become a burden to them so they'd have to look after me like a patient and I wouldn't be responsive to them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"There are people out there looking after people with dementia, with Alzheimer's, who are quite happy to do that, family members, and I know now my family if I had dementia or Alzheimer's would have looked after me in exactly the same way as those people. But in my head, I kept thinking, 'I'd rather not be here than have that.'

"But that was only fleetingly. The grandkids would come around and I'd get a lift from that and carry on again. In the days after that I'd get worse and my speech would deteriorate but it's fine now."

Depression got the better of Speed, whose suicide Kamara writes about in the book.

"Speedo didn't have apraxia, that's why it's so hard to get my head around what's happened to him," he says. "It's something I find really hard to accept.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I met him about a month before he took his own life when he did Goals on Sunday. I thought he was as happy as I'd ever seen him so you never know what's going on in someone's brain, you really don't."

What was going through Kamara's head at first was trying to muddle through. This was someone used to overcoming obstacles, signed up the Royal Navy as a 16-year-old because his dad did not want him playing professional football, then battling the empty-headed racism that followed black players at that time. Yet he not only played for his hometown club, Middlesbrough, but also the one he supported as a boy, Leeds.

So Kamara battled on, unaware how obvious the signs were to viewers, even if many mistook his slurred speech for drunkenness.

"The first 18 months of not telling anybody what was going on were so difficult, knowing I was in decline but refusing to admit it," he says now.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I ended up driving myself crazy by hardly talking at all, using soundbites so I could get away with it – or I thought I could – but obviously the people close to me knew I wasn't getting away with it. That was hard."

Admitting it was a massive release.

"The response was amazing," he says. "The football family was amazing. Friends, family, ex-team-mates, people I didn't know got in touch.

"From me not wanting to say anything to family and getting told off for not confiding in them because they really didn't know what was going on and perhaps could have helped me, I now realise there's always somebody out there to help you.

"In my case there were hundreds of thousands of people but if you're alone and you're thinking you can't tell anybody about your symptoms, do please tell them. Someone will always help you.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I've had Ben Shephard, Jeff Stelling, Steph McGovern, three people in TV who've just been so close to me and keep sending me love. They keep saying, 'You're fine, don't worry about it, we accept you as you are, don't give up, don't quit, carry on with TV.'

"I would be saying exactly the same to them but it's such a comfort that they've got my back as well."

Last year's documentary, Chris Kamara: Lost for Words, included a moving scene when he returned to his home town as a half-time guest for a Middlesbrough versus Bristol City game. He was greeted by a huge two-part banner reading: “You’re not a fraud (a reference to how he said he felt when first working with the illness) you’re unbelievable Kammy”.

"For them to hold up that banner and the whole crowd, even the Bristol City fans, singing, 'You're one of our own' – I don't know why they were singing along but they joined in," he chuckles, "it was a 'pinch me' moment which sent shivers down my spine. How has this happened? It's way beyond what you'd believe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"The majority of supporters at the majority of clubs came through for me. I got invited to 28 football clubs to go any Saturday I wanted, two tickets, to be their guest. I can't thank them enough. It's quite amazingly, really.

"I always think, 'Am I worthy of it?' There's so many more people, so many ex-footballers, who've done more than I have so why me? I suppose that was the impact of Soccer Saturday and Goals on Sunday."

And although he no longer works for either, his television career is not at an end.

"The future's good," he says. "The offers of work have never stopped and I'm able to do them better than I was six months ago."

Kammy: My Unbelievable Life is published by Macmillan, RRP £22.