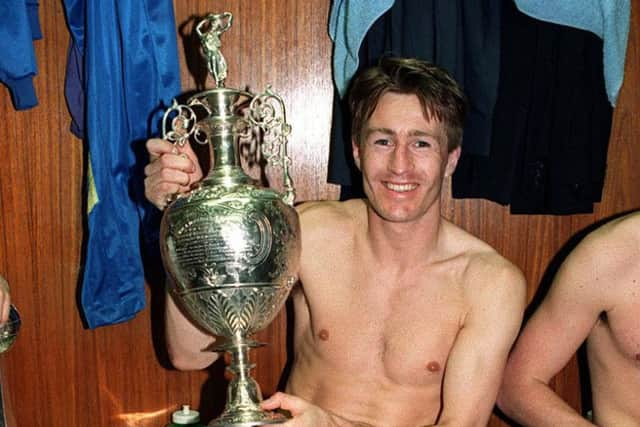

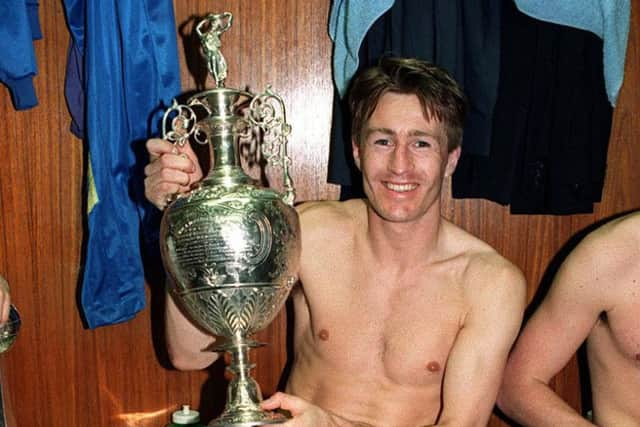

Leeds United '˜92: '˜It was a wonderful, unexpected achievement' - Lee Chapman

In 1992 Lee Chapman owned the most famous sofa in England. He saw it again recently during an edition of ‘Have I Got News for You’ as the satirical show made light of the contrast between Chapman’s idea of a title party and the mayhem in Jamie Vardy’s kitchen after Leicester City won the Premier League last year.

A smartphone captured Vardy’s moment in the way that smartphones capture so much these days. Twenty five years ago ITV were in Chapman’s living room to broadcast live as Manchester United’s defeat to Liverpool – the result which crowned Leeds United as Division One champions – played out on the television in front of him, Eric Cantona, Gary McAllister and David Batty.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was the early days of live TV,” Chapman says, “and you could tell that none of us knew what we were supposed to do. ITV wanted a party but it was all very surreal and awkward. At one stage someone said ‘can you celebrate with some champagne?’ I had to tell them we didn’t have any in the house.”

That story says much about the understated, unpretentious style of Howard Wilkinson’s squad. Even Chapman’s share of celebrity status did not equate to a cellar full of bubbly. Leeds’ title win was momentous, an unforeseen achievement in the eyes of the club’s players, and ITV had been badgering Chapman all week for an invitation to film from his home while Manchester United tried to save themselves at Anfield.

Chapman agreed, on the proviso that Leeds beat Sheffield United earlier in the day and put themselves on the threshold. He and his team-mates returned from a 3-2 victory at Bramall Lane to find the cameras waiting.

“My dad was a friend of Trevor East, the man who ran ‘The Match’ for ITV,” Chapman says. “My house was in a small village and they rolled in with a big, 30-foot mast and all this camera gear. The locals must have wondered what was going on.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We watched the game at Anfield and every now and then they’d cut to us from the studio, looking for a reaction.” At various points Chapman made a fist of translating questions to Cantona into French. “It was more like English with a Clouseau accent,” he jokes. “Looking back I don’t think it captured the moment. But then I don’t think the moment had really sunk in.”

Later that night, on April 26, Chapman and a larger group of Leeds’ players went for dinner at the Flying Pizza in Roundhay, the restaurant of choice for the great and the good. As they entered, the clientele rose and gave them a standing ovation which, as Chapman recalls, went on for five minutes. “That was the moment when we realised what we’d done and how much it meant,” he says.

Has the feeling of satisfaction faded during the 25 years in between? “Not at all. I can’t believe it’s 25 years. Where did that time go?”

Chapman likes the fact that Wilkinson – “a great, innovative manager” – is still the last English coach to win the country’s top division. It annoys him mildly that the final season of the pre-Premier League era is so readily forgotten or treated as second-rate. “It’s almost as if football started when the Premier League started,” he says. “I know why the likes of Sky see it that way, I understand the commercial side of it, but you do feel as if it’s been erased from history – not by anyone in Leeds but by many other people. It was a wonderful, unexpected achievement.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChapman remembers setting out at the start of the 1991-92 season with the intention of coming second. Wilkinson’s squad were fourth at the end of the previous year but, as Gordon Strachan put it, “a distant fourth” behind champions Arsenal. “One of the great things about Howard was how single minded he was,” Chapman says. “I’d played under him before at Sheffield Wednesday and it’s fair to say that he wasn’t the most charismatic man. He wasn’t a journalist’s dream. But everything was black and white.

“That season, before it panned out, he wanted us to finish as runners-up. Even when it looked like we had a chance of the title, he’d talk about aiming for second. Because of that, the title crept up on us. Psychologically most of the pressure was on Manchester United. They hadn’t won the league for 20 odd years and neither had we but it felt much more desperate from their point of view.”

Wilkinson’s great strength was in religiously applying the basics. Chapman, a cut-and-thrust centre-forward, scored 20 goals on the way to the title and found Wilkinson’s consistent management helpful. Mick Hennigan, United’s assistant, was something of a foil for Wilkinson’s serious demeanour. “Howard was aloof as managers can be, someone you weren’t going to be mates with, but Mick was almost good cop to his bad cop,” Chapman says.

“He was broad Yorkshire with a great sense of humour and a humble attitude. I felt we was an under-rated, someone who didn’t got enough credit for his part in it all.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But Howard was so particular. Some managers hope that it happens on the day but he drilled things into us to make sure that it did. Everything was done to the Nth degree. He was big on research and he’d make us watch videos of full games – pure torture if you’d lost or had a bad day. That was pretty new to me. On Fridays we’d rehearse set-pieces for ever. Those sessions went on and on until you were tearing your hair out. But then you’d turn up for a match and you’d do it all perfectly without even thinking about it.

“He wanted goals from me, obviously, but beyond that as the target man he only asked me to hold the ball up and look for players like Gary Speed and Rod Wallace buzzing around me. You had Strachan, McAllister and others as well. In a sense it was very easy for me.

“So often as a target man you’ve got nothing around you so you get robbed and disheartened. I’d never played in a team with so many options. I got 20 goals and I was happy with that. I’d have got a few more if I hadn’t broken my wrist in the FA Cup. I was so desperate to play that I came back from that with a cast on.”

Strachan, by common consensus, was the heartbeat of Wilkinson’s team, an inspiration on days when Leeds had none. When Chapman thinks of him, he thinks first of the last-ditch volley against Leicester City in 1990 which kept the club’s bid for promotion from Division Two breathing and kept the journey under Wilkinson on course.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“That was Strachan,” Chapman says, “and that day was the best example of what he gave us. None of the rest of us were going to come up with anything. We were down and out. He was the driving force.”

For so much of the season the initiative stayed with Man-chester United, Strachan’s old club. Strachan told the YEP last year that he feared the title had gone after Leeds lost 4-0 at Manchester City on April 4, a mere 22 days before their decisive victory over Sheffield United at Bramall Lane. “It was one of the games when the pressure got to us,” Chapman says. “Everyone could see that we were in with a great chance but that result brought us back down with a bump.”

What happened next was like poetry. Manchester United drew at Luton Town, lost at home to Nottingham Forest and then travelled to 22nd-placed West Ham United for a midweek away game. Kenny Brown scored the only goal of the night at Upton Park, a somewhat unintentional volley which arced around Peter Schmeichel, condemned Alex Ferguson’s side to a 1-0 defeat and put Leeds in the box seat with two games to play. “I played with (Brown) at West Ham,” Chapman says. “I don’t remember ever seeing him score. The game was crucial, we knew that, so I was following it on Teletext. When he came up with the winner you kind of thought it was meant to be.”

It set the scene for the following Sunday, when a win for Leeds at Sheffield United allied with a defeat for Manchester United at Anfield later that afternoon would send the title to Elland Road. Leeds fought out a 3-2 victory at a windswept Bramall Lane in a manner which makes Chapman laugh. Two own goals, one conceded by him, summed up a day when crossing the line was United’s first and last concern. “It was an awful game,” he says. “All of the goals were terrible but by that stage you were just trying to get the job done.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver 42 games, that squad – as Chapman and his former team-mates always stress – had far more about it than a belligerent streak. Between Chapman’s instinctive poaching, the dreamy midfield quartet of McAllister, Batty, Speed and Strachan and a defence who conceded 37 times, Wilkinson’s squad had the pedigree of champions. Of all his goals, Chapman picks out one from his hat-trick in a 6-1 thrashing of Sheffield Wednesday at Hillsborough midway through the season as an emblem of Wilkinson’s team.

“It’s (John) Lukic to Tony Dorigo, Dorigo to Gary Speed on the left wing and then a lovely cross from Speed for me to put away a diving header in front of the Leppings Lane end,” Chapman says. “It epitomised that team. That was us.”