McEnroe left to rue the day he had unveiled Wimbledon secrets to apprentice Agassi

The bookends to his 15-year odyssey in SW19 were a 3-6 3-6 6-4 4-6 loss to Jimmy Connors and a 4-6 2-6 3-6 beating by Andre Agassi.

Those bald statistics offer a rare example of symmetry in the volcanic American’s years of performing on sport’s most famous green sward.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEven the clearly defined geometry of the court itself was challenged at times by McEnroe, who occasionally seemed to see balls fall outside the lines when they were given in, or drop inside the lines when they were given out.

But, although he was booed when kicking his racket during his debut quarter-final win, his regular railing against perceived injustices heaped upon him by umpires and line judges would not become totally synonymous with his name until he stepped into the professional ranks.

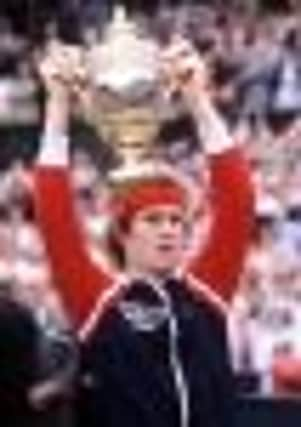

For it was as an amateur that McEnroe, aged 18, set a new record for the most consecutive wins in one year at Wimbledon when, in 1977 – the event’s Centenary – he came through three qualifiers and five matches proper.

Some traits we would become familiar with were already on show, such as the trademark headband which always appeared on the verge of defeat in its attempt to hold back a mop of infeasibly unruly hair.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo, too, was the sublime half-volley picked off his toes as he raced to the net when the opponent must have felt sure he had hit a winning return against a player who would go on to be revered as one of the greatest serve-and-volley exponents the sport has seen.

Yes, people used to play the serve-and-volley game at Wimbledon. In fact, most of the men did, and a lot of the top women. Bjorn Borg’s five successive Wimbledon triumphs from 1976 through to 1980, achieved with a game which centred around play at the back of the court, throttled the argument which said baseliners could not have sustained success on grass.

Along, therefore, came baseline battlers such as Agassi, who, with his flowing crinkled hair and aggressive two-handed shots on both the backhand and forehand – each accompanied by ferociously loud grunts – looked like a tennis incarnation of the Slag Brothers, the Prehistoric contenders in the cartoon Wacky Races.

Las Vegan Agassi had yet to win a grand slam in July, 1992 and although his precocious talent suggested it was a matter of time, grassbound Wimbledon seemed the least likely of the four grand slam events to provide the opportunity of a breakthrough.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGiven McEnroe’s pedigree on the South West London courts, it was not surprising that Agassi would turn to him for pre-tournament advice as to how he could adjust to the demands of playing on grass. What the three-time champion could not have known is that he was handing the 22-year-old the weapons with which he would end his own dreams of a fourth crown in the twilight of his playing career.

McEnroe had dipped to world No 30 entering Wimbledon 1992 but battled through to the semi-finals on a wave of public and press support. The realisation that they were witnessing the final embers of a coruscatingly vivid career meant that even those who had once hated him for his boorishness were fanning those ashes with cries of encouragement from the stands or articles of encouragement in the media.

Pre-match, Agassi both acknowledged the recent assistance McEnroe had given him while swatting sentimentality aside with the severity of a two-fisted groundstroke winner.

“There’s probably a chance he wishes he hadn’t been practising with me quite as much these last two weeks,” he commented. “Whatever he’s helped me with, it’s something he’s probably second-guessing right now.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I don’t think there’s any one player happier for John than me but the semi-final’s going to be nothing personal, just business.”

That business involved the surrender of only nine games as both the speed and power of his shots proved overwhelming. McEnroe hugged Agassi at the net and, with the wry humour with which he now imbues his incisive TV commentary, said: “Why did you listen so well?”

“Andre was still so wet behind the ears that I had to remind him to bow to the Royal Box on his way off the court,” recalled McEnroe in his autobiography Serious.

“Here was a kind of sweet poetic justice. In my final Wimbledon singles match, I was teaching manners to the next generation.”

Serious: Published by Little, Brown (hardback), Sphere (paperback).