Far from home

The Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery is a bit of a hidden gem. Housed within the Parkinson Building at the University of Leeds, it programmes a series of exhibitions throughout the year – and its latest show is something of a revelation.

György Gordon (1924-2005) A Retrospective explores the extraordinary life and work of the little known émigré artist who fled to the UK as a refugee from the Hungarian Revolution in 1956 and eventually settled in Wakefield where he was a lecturer at the College of Art for more than twenty years. The timing of the show in the 60th anniversary year of the uprising is poignant and very apt.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe retrospective was suggested by Peter Murray, founder and director of the Yorkshire Sculpture Park who was a friend of the artist’s. At the opening in Leeds last week Murray spoke movingly about Gordon and referred to him as “one of the most under-rated of British artists.” The exhibition is an opportunity to introduce his work to a much wider audience.

Curator Nathalie Levi worked with the YSP and Gordon’s estate to put the show together, selecting a group of forty works which demonstrate the artist’s talent, range and preoccupations. “Some of the pieces are related to things he witnessed during the Second World War, when as a teenager he worked as a part-time ambulance driver and then later as a refugee,” she says. “There are faceless figures and others that appear to be shapeless masses. Some of the work is quite difficult to look at and is a reflection on the consequences of political, social and private upheaval.”

There are some very dark abstract works which speak of despair and alienation and which obviously relate to his personal experience of flight and statelessness. Refugees (1964-65) is very much in the style and tradition of European Expressionism. Painted in sombre tones, there is a sense of turmoil and chaotic movement, with hostile swirls of light in the foreground and indistinct images of the distorted human form. The Torso series of works created 1969-70 – some examples of which are in the show – are very challenging and reminiscent of Francis Bacon’s paintings in which the human body loses its humanity.

“In person, according to people who knew him, he had a wonderful sense of humour and he was really gentle and philosophical,” says Levi. “He was also a very kind and nurturing teacher. I think the darkness of his experiences was channelled into his work.” It is clear looking at many of the paintings, some of which are incredibly moving, that Gordon never quite left behind those feelings of alienation and trauma that are an integral part of being forced to flee your home. “He viewed emigration as a sort of death,” says Levi. “And he spoke of how when you leave your homeland you lose a part of yourself.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

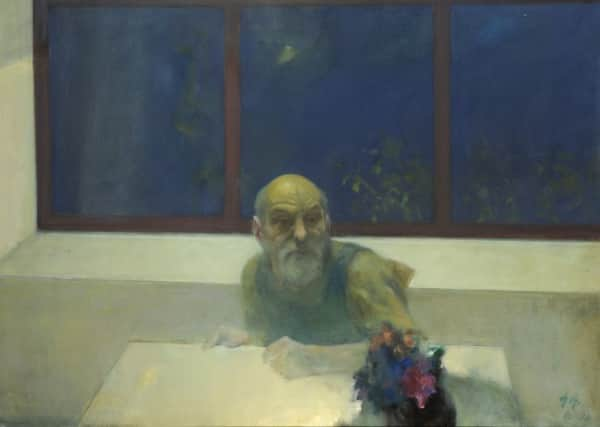

Hide AdHis later work is not quite as dark and moves from the abstract towards a more figurative style – there are lots of self-portraits. That’s not to say that they are any less thought-provoking or unsettling. It is clear that Gordon was not afraid to confront his own mortality, starkly documenting the ageing process and the sense of isolation that can come with that. Many of his figures from this period seem to be trapped in a half-life. Two paintings stand out for Levi, she says, Self Portrait with Window which she feels is “really representational of him”. He looks kind, curious and almost impish; you can sense the humour and playfulness. The other work she mentions is Mourning. “I think it pertains both to literal loss and the metaphorical grief of leaving home behind,” she says.

His flight from Hungary was particularly difficult and traumatic. His mother had just died – there is a terribly sad and intimate painting in the exhibition entitled Mother on Her Deathbed – his marriage had ended and he fled with his seven year-old daughter Anna to Austria. They managed to get to America where Gordon was interrogated, interned and sent back to Europe. He was then imprisoned in Salzburg for 30 days and separated from his daughter who he didn’t see again for several months until the Red Cross reunited them in London.

There, a few years later, he met his second wife, pianist Marianne Mozes, also a Hungarian émigré, and their son Adam was born in 1963. The following year he took up the post of lecturer at Wakefield College of Art.

“Moving to Yorkshire changed his life but it also changed his practice too,” says Levi. “He was trained at very orthodox academies in Budapest, then he went on to do landscapes and still life paintings for the Communist regime according to very strict briefs. It was only after coming to the UK that he had more artistic freedom.” Gordon’s dedication to his teaching, however, meant that he had less time to spend on his own painting and drawing. “In many ways he put his teaching before his own work,” says Levi. “He was never an attention-seeker or self-promoter but he was a remarkably skilful and talented painter. Although he wasn’t very widely known beyond West Yorkshire, he got more recognition in later life – there was a touring exhibition that went to the National Portrait Gallery – but not nearly as much as he deserved.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds until February 25, 2017.

On November 21 at 6pm as part of the University’s Being Human Festival there will be a free public lecture on the 1956 Hungarian Revolution given by Professor Simon Hall.

***

Born in 1924, Gordon entered the National Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest in 1948, going on to work as a newspaper illustrator and graphic designer.

After fleeing Hungary in 1956 he worked in commercial art studios and advertising in London from 1957 to 1961.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1992 Gordon returned to Hungary for a major retrospective of his work at the National Széchényi Library in Budapest, driving the work across Europe himself due to a lack of funding.

In 2001 he won a commission from the National Portrait Gallery for a group portrait of Sheffield-based Lindsay Quartet.