Lucy O’Brien: ‘It’s only now somehow that you realise how much Dusty Springfield achieved’

Biographer Lucy O’Brien would be the first one to admit her impressions of singer Dusty Springfield have changed since her book on one of the biggest British stars of 60s pop was first published in 1999.

Once viewed as a troubled figure, battling with addiction and industry pressures to keep her sexuality secret, the 20 years since Springfield’s death have seen her championed as an LGBT heroine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was expecting this to be quite a quiet update of the book, just in that there’s a film coming out [starring Gemma Arterton] and it was 20 years since she passed away and it seemed like a good time to remember her and do some extra interviews that I hadn’t had time to do before the 1999 version,” O’Brien says. “But then it was one of these things that started to snowball. The more I talked to people, the more I thought about her life and career again.

“There’s still loads of incredibly enthusiastic fans and there’s this Dusty Day every year in Ealing where, for instance, I saw Julie Felix play this year and Simon Bell did a set. There were so many people there. They were partly raising money for the Royal Marsden Hospital, where Dusty was before she died, but I think it’s almost as though her influence has grown. It hasn’t diminished with time, it’s just increased.

“I think maybe with everything we know now about the various aspects of her life – her struggle with addiction and her being a lesbian and not being able to be out of the closet in 1960s pop and what it was like being a woman at that time in the music industry, fighting to be heard and to create the sounds that she wanted to create. It’s only now somehow that you realise how much she achieved and the strength that she needed to achieve that.”

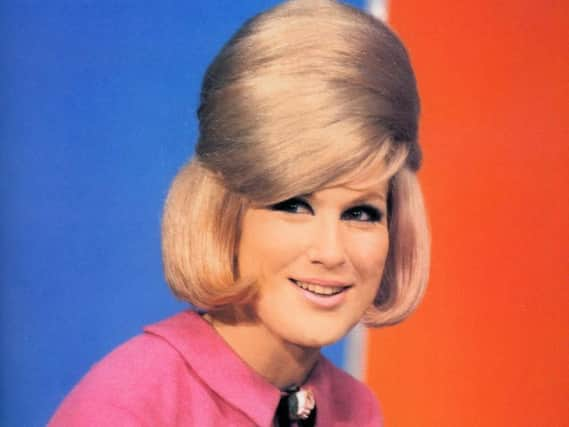

Born Mary O’Brien, Springfield grew up in a middle-class family in West Hampstead and High Wycombe. At convent school she showed promise as a singer; at 16 she decided to reinvent her appearance, pairing a peroxide blonde beehive with heavy eye make-up. “She classed herself as a misfit,” Lucy O’Brien says. “Part of that I wonder if it was because of her sexuality, from very early on she didn’t feel like she fitted into the romantic narrative, boy meets girl, girl gets married, woman has children and lives happily ever after.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She also had this extraordinary talent in being able to sing in such a unique way, I think that became her pathway. She grew up in that 1940s-50s quite strait-laced suburbia and I think that wasn’t a good fit for her. She was actually quite a wild one and I think being a performer really gave her an outlet for that, it was a channel for her feelings.”

In 1960 she joined her older brother Tom and his friend Tom Feild in The Springfields, a trio whose sound incorporated pop, rock ’n’ roll, folk, country and world music. Although she had tired of playing “happy, breezy music” by 1963, the band gave her “loads of experience and taught her about stagecraft and how to sing in the studio” which stood her in good stead when she launched a solo career with I Only Want To Be With You.

The move had been planned, “so there wasn’t a huge amount of acrimony when she left The Springfields”, O’Brien says. “She’d always had it in mind that she wanted to be a solo artist and really get stuck into that mix of soul and pop. She was quite frustrated in the beginning. I remember her saying to me when I did the interview with her, that she felt what she’d been doing was bringing sounds into British studios that hadn’t really been made before, and being quite exacting with the session musicians. She was only about 23 or 24 and she’s telling session musicians how they should play and working really closely with Johnny Franz, the producer, and Ivor Raymonde, the arranger, and I actually think when you look back on it she played such an active role in the studio that actually nowadays she would get a co-production credit, if not a full production credit, whereas then, because of the sexist industry, people didn’t even consider that. She was such an innovator in terms of British pop music.”

A string of hits followed, including the number one You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me. In the US, Springfield performed with soul and Motown artists; on a South African tour in 1964 she caused controversy by refusing to play to segregated audiences and the apartheid regime deported her. “I think about the bravery to stand out and do that,” says her biographer. “Now there’s been a lot of anti-racist work so artists feel supported if they want to speak out against racism, but back then the prevailing view was that pop singers didn’t get involved in politics. She got hugely criticised and people saw her meddling in South African affairs because at that point Britain still had a strong relationship with South Africa even though apartheid was absolutely abhorrent.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1968 Springfield made her masterpiece, Dusty in Memphis, with Jerry Wexler, Arif Mardin and Tom Dowd. O’Brien says: “She was absolutely terrified, there she was in the studio that Aretha Franklin had recorded in, with the production team behind Aretha Franklin and top Memphis session players. At first she kind of froze but then after a while she was way out of her comfort zone but Jerry Wexler managed to get an amazing performance out of her. And it wasn’t just her…because she set her sights so high, I think that inspired the musicians and producers around her. Everyone was playing at the top of their game.”

Two years later Springfield moved to Los Angeles, where she continued to make music but without the same commercial success. It affected her mental health and she became addicted to drink and drugs. While writing the book, O’Brien says she followed in the singer’s footsteps and found LA “a beautiful place but very alienating, if you don’t have a strong family or friends network around you I can understand how people can fall between the cracks”.

There was, however, a comeback in the late 1980s when Springfield teamed up with the Pet Shop Boys on the hit singles What Have I Done To Deserve This and Nothing Has Been Proved and the album Reputation. O’Brien believes this was a “turning point” for Springfield and by the end of her life she felt appreciated again. “When she came back and recorded the Reputation album, which did really well, and she had more hits, I think that was a vindication, she felt validated and welcomed and really grateful. I suppose she probably felt what I felt when I updated this when I was doing events and panel discussions. I’ve just been amazed at the response from people, that there is so much love for her. When you think about the history of British pop music and female singers in British pop, she stands out as one of the best if not the best. I think we’re just really proud of her.”

O’Brien’s own career as a music journalist began while she was studying at the University of Leeds from 1980 to 1983. She became music editor of the Leeds Student and was in a punk band herself as well as a short-lived band with Kevin Lycett from The Mekons, “he had this idea of a girl-group doing Dusty Springfield covers”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’ve got very fond memories of Leeds, I loved living there,” she says. “It’s always had such a strong music scene. I was there during post-punk and there were so many bands that we went to see every other day, there were bands on in the Union and the Warehouse had just been opened. What really attracted me to Leeds in the first place were bands like Gang of Four and Delta 5, I loved that sound, and then Soft Cell. I remember seeing all the post-punk bands like Cocteau Twins and Bow Wow Wow and The Au Pairs and I remember seeing a very early Spandau Ballet on their first tour at the X Club, they were very slick and had extremely white socks.”

She would go on to work at the NME with the likes of Charles Shaar Murray and Nick Kent. It’s an era she describes as “like going to work at this elite college, you felt like you were always being tested and pushed and you never quite knew why, it was probably because all the writers were incredibly competitive with each other for space and to write about the bands they wanted to write about, which in one way was quite good, it really spurred you to do the best you could but there were very few female writers and it was like that for quite a long time.

“Also very few women featured in the pages of NME, it tended to be on the whole male bands and artists, so I guess I made it my business to interview female artists whenever I could and fight for proper space for them so that they weren’t written about in a way that wasn’t just about their personal lives. It’s interesting, female artists often get asked about what they wear and their boyfriends but not about their music. It sounds strange but that was so often the case, and still is, to a degree.”

O’Brien would later develop these interviews into the book She Bop; she has also written biographies of Annie Lennox and Madonna. She is presently working on a book with Skin of Skunk Anansie. “There has been quite a lot of stuff about the 90s and Britpop and Skin has such a fascinating story that is a different narrative about being British in the 1990s, and also going up to the present day and the last humongous tour that Skunk Anansie did. I think people are beginning to realise that this band has been together for 25 years and they’ve really contributed a huge amount to British pop and rock culture and deserve to be properly recognised.”

Dusty: The Classic Biography Updated by Lucy O’Brien is published by Michael O’Mara Books, priced £16.99.