Nostalgia on Tuesday: Fighting fires

The fire was discovered at about 5am by three housemaids, who were awakened by the knocks of a chimney sweep. The Green Room floor and the ceiling of the grand saloon were ablaze. They raised the alarm and the butler and second coachman took turns throwing buckets of water on the fire as fast as 12 servant girls could bring it in. They were eventually driven out by the smoke and flames. The man who was in charge of the water-pumping engine was sent for, as well as the plumber, but all the taps were frozen and it was some time before the snow, which had fallen heavily during the night, could be swept away from the ground to find the fire-plugs.

A small hand engine kept at the house was set to work in the hall, and the Kirkbymoorside fire engine and brigade were sent for. Both engines were delayed, owing to the water pipes being frozen and only a poor supply of water could be pumped up from the river Rye.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe fire continued to spread and it was decided to send for the steam fire engine from York. This arrived by special train at about 11am but was too late to prevent the centre of the building being gutted.

All this begs the question: how did our efficient and reliable fire brigades develop? At the time of the Duncombe Park incident, engines and crews were largely organised by voluntary bodies and insurance companies, and protection of life was not always the main objective. Earlier, in the 1820s, James Braidwood had founded the world’s first municipal fire service after the Great Fire of Edinburgh in 1824.

Braidwood later moved to London to become superintendent of the London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE) but was killed whilst fighting a fire in 1861. After much pressure from liability-laiden insurance companies and LFEE, the Metropolitan Fire Brigade was created in 1866, becoming the London Fire Brigade in 1904.

A series of Acts introduced towards the end of the 19th century made new local government bodies take over the responsibility for fire fighting.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

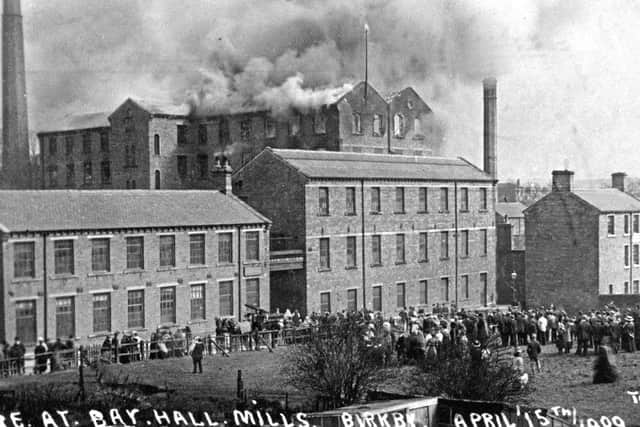

Hide AdA report on the Albion Mill, Morley, fire on July 15, 1905, revealed a good level of organisation by two local fire brigades who were called to confront the blaze. Albion Mills were owned by R and J Horsfall, cloth manufacturer, and the fire broke out in one of three large buildings.

On the alarm being raised, the Morley Corporation Fire Brigade was said to be “quickly on the spot” and was followed about 20 minutes later by the Leeds Brigade. The engines of both brigades found ample supply of water in the nearby dam, and hosepipes were also fixed to the town’s mains. But, by this time the fire had got firm hold and it quickly enveloped the whole building.

An adjoining building was endangered, but the efforts of the firemen were successful in preventing the spread of the fire. The mill was eventually gutted destroying machinery and material. The damage was estimated at £8,000 and about 250 workers were affected.

A disastrous blaze at Bradshaw Mills, Moorbottom, Honley, in May 1924 underlined that a fire brigade’s response time was good. Members of the Huddersfield Fire Brigade arrived within 20 minutes of being alerted. A plentiful supply of water was obtained from a nearby street hydrant but little could be done to check the progress of the fire.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough firemen were more adept at responding to the call of fire, they were also made aware of the dangers they faced. At Honley, when the roof collapsed, firefighters narrowly escaped being struck by falling masonry.

The Fire Brigades Act of 1938 placed responsibility for the provision of a fire brigade on a local authority (excluding London). The Act was in force until 1941 when all local authority fire services were put in the hands of the National Fire Service. The Fire Services Act of 1947 put the fire brigades back into local authority control with effect from April 1, 1948, in England and Wales and May 16, 1948, in Scotland.

In turn this Act was replaced by the Fire and Rescue Services Act of 2004. Clarifying the duties and powers of fire authorities, the intention of the Act was to promote fire safety, fight fires, protect people and property from fires, rescue people from road traffic incidents, deal with other emergencies involving flooding or terrorist attack, and do other things to respond to the particular needs of communities and the risks they face.

Today it would be rare to find modern mill fires depicted on postcards, yet they still make headline news and are dealt with under a number of carefully considered procedures and involving the latest fire-fighting equipment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

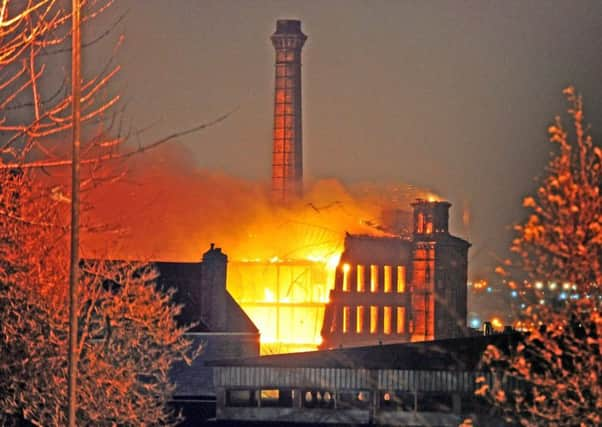

Hide AdDrummonds Mill fire on Lumb Lane, Bradford, on January 28, 2016, illustrated the West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Service’s level of proficiency and the positive response by the local authority to a major conflagration. Residents from around 100 homes in Lumb Lane and Grosvenor Road were quickly evacuated and taken to the Richard Dunn Sports Centre. This was carried out as a precautionary measure due to high levels of carbon monoxide in the atmosphere.

Afterwards firemen worked with demolition men at the site while Bradford Council offered support to business owners affected by the fire.