Showcase '¨ for keeps

The three of us are standing in a desolate, unlovely corner of the city centre, across the road from a now-closed “alternative fashion shop” prophetically called Oblivion. We’re peering through small windows in the hoarding around an urban prairie where the 1960s Castle Market stood until it was demolished earlier this year.

Gorman, the Friends’ chairman, points to a locked doorway leading down to a room housing a 15ft square lump of masonry that’s one of the castle’s few known relics. I went down there myself some years ago and did a complete circuit of the ruins. I walked very slowly, but it still took less than half a minute.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMy guide at the time, however, urged me to view this fragment through the eyes of history. He offered a panoply of pageantry, a tapestry of drama and intrigue, from the long-gone days when the centre of Sheffield was graced by orchards and avenues of walnut trees. As Gorman says: “It’s all about using your imagination.”

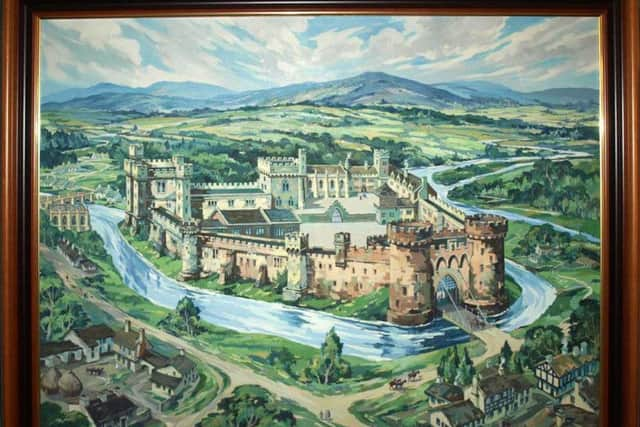

The Friends are hopeful that there are more remains waiting to be discovered. The 13th century castle, after all, was a magnificent structure, if artists’ reconstructions are anything to go by. It had towers and turrets, an imposing gateway, a chapel, a drawbridge, a Great Hall and an atmosphere of medieval romance.

“It wasn’t a castle that was renowned for major battles,” says Gorman, who works as a relationship director at NatWest Bank. “It was more a residential castle.” Hence its role as a prison for Mary Queen of Scots – who brought a 40-strong entourage with her. Three years after leaving Sheffield, she was executed in Northamptonshire, aged 44.

At that time, the castle was, as an early 17th century survey noted, “a very substantial and impressive building”. It dominated the city. “Sheffield is all castle,” Sir George Sitwell, father of the celebrated literary trio, remarked after studying a 14th century map (now lost) of the city.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the Civil War, the castle was besieged by the Parliamentarians, who subsequently dismantled it and left it to be pillaged for stone. And that was that. Over the next 300 years, Sheffield busied itself with building its industrial future rather than cherishing its architectural past.

The city more or less forgot about its castle, though when the future King Edward VII visited in 1875 it featured on a 100ft long screen that hid unsightly slaughterhouses from the royal gaze.

The Friends are hoping to trace the original designs for the screen and recreate it as part of their vision for the regeneration of the city’s Castlegate area (the castle’s site). Sheffield City Council may transform the area into a small park, and, as the Friends see it, the most urgent need is to excavate the site.

Opportunities to do so have been missed over the years, says David Clarke, a senior lecturer in journalism at Sheffield Hallam University. It’s a question of funding. Two years ago, plans suffered a temporary setback when the Heritage Lottery Fund turned down a £362,000 application to start the process of making the castle a visitor attraction.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGorman sees the current state of the site as “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” to excavate. “Though I think we have to be realistic,” he says. “We’re not expecting to find huge remains down there, but the footprint of the building will be there.” As another Friend has remarked: “We’re not digging up Camelot.”

Over the years, successive redevelopments of the site have unearthed some interesting finds. In 1927, for instance, when a new Brightside and Carbrook Co-op store was being constructed, tantalising “historic relics”, as the Co-op called them, were discovered in “black tenacious sludge, none too fragrant”. They included a crucifix, gold pins and pottery.

The Co-op produced a whimsical little booklet to celebrate. “A new palace has been built, more beautiful than the old castle,” it rhapsodised. “Where mannequins now parade, courtiers and their ladies once paced. Battle raged outside the castle gate on land which is now the property of a great democratic concern.”

Then as now, no-one really knew how the castle looked in its heyday. And that’s part of the attraction for the Friends.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There are no plans, drawings, paintings or etchings of it as it was and that adds to the mystery of it all,” says Gorman. “Which other city in the UK has a hidden castle? This was the birthplace of the city of Sheffield and it’s an opportunity to tell that story.”

Clarke is particularly interested in the underground passages and tunnels rumoured to link the castle to other parts of Sheffield. They may have been used by Mary Queen of Scots’ gaolers to smuggle her in and out.

“I heard the rumours in childhood from my grandparents and always assumed they were either folklore or simply the remains of ice houses and privies,” says Clarke, who will be giving a public lecture on the tunnels in September.

“It’s an intriguing mystery that has never been resolved and this could finally be the chance to get to the bottom of it. There’s a huge draw in things that are mysterious.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Nationally the perception is that Sheffield doesn’t have much history other than in terms of cutlery and steelworks, but the possible excavation of the castle might change all that.”

It may answer the question posed by the poet Francis Buchanan a century ago as he contemplated the castle site:

“Spectre of time! Where are thy relics resting?

Where are thy battlements and lordly hall?

No vestige here, no stone with noble crest in,

Nor remnant of a buttress or a wall.”

Sheffield: the Camelot of the North? Well, maybe.

For more information visit friendsofsheffieldcastle.org.uk