With a retrospective on at Tate Liverpool, Sir Don McCullin talks about Vietnam, Bradford and his big break

His work spans more than 60 years, during which time he has captured images of conflict from around the world, including Vietnam, Northern Ireland and Lebanon, travelled across the North of England recording the lives of people in our towns and inner cities, and photographed The Beatles for Life magazine.

And yet his career could easily have ended before it had even started. “I actually failed my trade test to become a photographer in the air force and I left as an unclassified photographer,” says McCullin.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had been called up for National Service with the RAF and after postings to Egypt, Kenya and Cyprus he returned to London and began taking photographs in 1958, documenting his surroundings and local community in his native Finsbury Park.

The following year, his photograph The Guvnors, a portrait of a notorious local gang, was published in The Observer, launching his career as a photojournalist.

“It was published on a Sunday and I was offered every job in England the following morning. That one picture was like winning the Lottery, because I wasn’t really a photographer so I had to do some quick pirouetting and learn about photography and teach myself and that’s what I did.”

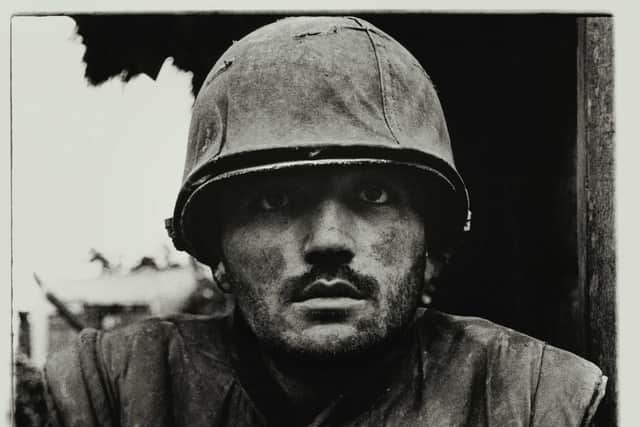

Now, seven deacdes later, more than 250 of his photographs are on display at Tate Liverpool. This major retrospective, originally shown at Tate Britain in spring last year, features some of his war photography, including his Shell-shocked US Marine, The Battle of Hue and his harrowing Starving Twenty Four Year Old Mother with Child, Biafra, both taken in 1968, alongside his work made in the north of England, his travel assignments and his breathtaking landscape shots.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs well as McCullin’s hand-printed silver gelatin prints, the exhibition also includes his magazine spreads and the helmet and Nikon camera which took a bullet for him in Cambodia.

McCullin’s photographs offer a visual record of some of the key historical moments of the last 60 years. In 1961, he travelled to Germany on his own initiative, funding the trip himself, to photograph the building of the Berlin Wall. The subsequent images he took won him a British Press Award and he went on to capture major conflicts around the world from Vietnam and the Congo to Cyprus and Beirut.

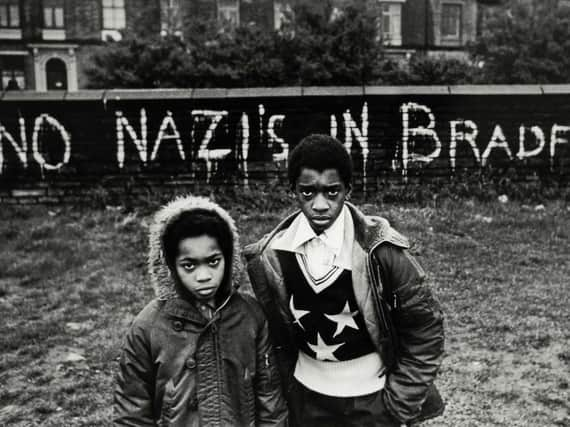

But while he is perhaps best known as a photojournalist and war correspondent, he has also consistently engaged in documentary photography in Britain, depicting life in some of the North’s deprived industrial heartlands during the 1960s and 70s. Having come from a poor working class family himself, he identified with the people who lived there and was committed to the practice of ‘reporting back’ and publicly highlighting these areas that were largely unseen, or ignored, by the politicians and the middle classes.

Yorkshire, and one place in particular, became a familiar stomping ground. “The most important place I based my North of England work on was Bradford,” says McCullin. “It’s the kind of place I could walk around blindfolded. It’s a place where you can’t miss as a photographer. It’s got that Hogarthian feel about poverty and loneliness. I said to somebody once in Leeds, ‘do you ever go to Bradford?’ And they said ‘why would I?’ And I said ‘because it’s fascinating.’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe found himself drawn to the city time and again. “I was walking around Bradford one day and a woman came up to me and said, ‘are you from the Press?’ And I said ‘yes’ and she said, ‘come into this house, I want to show you how we’re supposed to live.’ This kind of thing happened a lot, the people there were very open and they aren’t in most parts of England,” he says.

“It made me enjoy my photography, that’s why I like Bradford because I was enjoying taking photographs even if the subject matter was often quite hard and was about poverty and people who didn’t have a fair crack at the whip. I was enjoying myself and feeling guilty at the same time that I was enjoying myself because I was photographing people’s poverty and unhappiness.”

It was during the 60s that McCullin honed his craft with his social documentary work and war photography. He says Nigeria’s Biafra War, which killed more than a million people, including many women and children through starvation, had the most profound impact on him. “I’d seen too many Hollywood films and thought war was glamorous and that was a turning point when I realised that it wasn’t glamorous at all. I was looking at the people who pay the highest price in war and it’s not always the soldiers, it’s the civilians.”

If this was his most harrowing assignment, covering the Tet Offensive in 1968 ranks among the most dangerous. “I was in the citadel of Hue, the ancient capital, and that’s where I saw the fiercest battle of my life. That comes back to me all the time because I think, ‘Christ, how did I get out of that one?’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was while covering the war in Vietnam that he took what has become one of his most recognisable photographs – of a shell-shocked US marine. “It didn’t jolt me when I made the final selection for The Sunday Times because I actually passed it up. It wasn’t until I looked at it later on when I started printing it. But there’s a danger of making things iconic because iconic is sometimes comfortably, beautifully acceptable and you have to be careful of that.”

McCullin has had a few close shaves over the years. “In Cambodia, the first day in the field my camera got a bullet.” A week later he was hit in the legs by shrapnel from a mortar shell fired by the Khmer Rouge.

“When I came back from those wars I would immediately throw myself into my own personal journeys like going to Bradford or Liverpool, or I’d head up to Scotland to do landscape photography. So I never had time to feel sorry for myself or to think about post traumatic stress.”

In later years, McCullin has spent more time photographing the wide open panoramas near where he lives in Somerset. But even in his late 70s he found himself drawn back to conflict zones – covering the siege of Aleppo in Syria and returning to the country in 2017 to document the deliberate destruction of the ancient site of Palmyra by the so-called Islamic State. So why did he put himself in harm’s way again?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Because it’s in my blood. I felt like a bullfighter and I had to be in that ring. Then when you get there you think ‘you silly sod, why are you here?’ It was like playing Russian Roulette which one shouldn’t be playing at that age. It’s not fair to your family to go off and have them worrying about whether you’re going to come back.

“I’ve done some reckless, irresponsible things and took a lot of chances and managed to get away with it. But many people I’ve known didn’t get away with it and it’s not worth dying for a photograph.”

And yet photography has been his compulsion. “I never intended to be a photographer. I always blame photography for finding me, rather than me finding it,” he says.

“I was very naive when I was a young photographer, I didn’t realise how big the horizon was that I’d have to walk towards. It’s a never ending journey and I’m still doing it at the age of 85.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Don McCullin exhibition runs at Tate Liverpool until May 9, 2021. For booking details call 0151 702 7400, or visit www.tate.org.uk/liverpool

Support The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today.

Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you'll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers.

So, please - if you can - pay for our work. Just £5 per month is the starting point. If you think that which we are trying to achieve is worth more, you can pay us what you think we are worth. By doing so, you will be investing in something that is becoming increasingly rare. Independent journalism that cares less about right and left and more about right and wrong. Journalism you can trust.

Thank you

James Mitchinson

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.