After football, there’s still life

The ball was nowhere near them at the time and neither was the ref who saw nothing of the incident. But the linesman had spotted the sly smack in the mouth and so had some in the packed crowd at the Arsenal versus Newcastle United match. The Arsenal centre forward was duly sent off.

John still doesn’t know quite why it happened. Although he does concede that his view of his role as a centre half was to go in hard against his opposite number straight from the kick-off “because they’d never send you off in the first five minutes”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter many seasons of tumult on pitches at the top and the bottom of football’s pyramid, feted and lionised for his exploits, John has now switched to a more contemplative and reflective means of making a living.

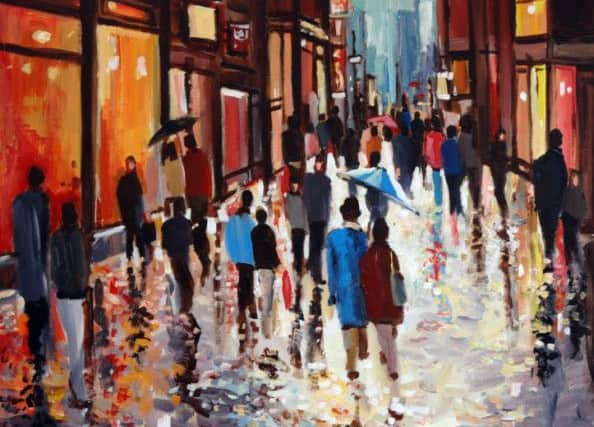

So complete has been the change that in his stylish workplace there is no hint of football at all, no memorabilia or echoes of a glamorous sporting past. Instead it is stuffed with original portraits, landscapes, wildlife images, photographs and prints, plus picture frame samples and bubble wrap. There’s a poster on the wall urging browsers to “Spread the Cost of Contemporary Art”.

In the far corner is an easel where John stands painting when he’s not busy with customers in his two-floor gallery situated a short step off the handsome main square of Bawtry, near Doncaster. “I work in fits and starts, I don’t mind noise,” he says.

John shows his own work and that of 25 other artists and has an international reputation. Recipients of his paintings include Prince Edward, the Duchess of Wessex and the Governor of Hong Kong. Tate Britain invited him to London to take part in a collaborative project and exhibition where 30 artists selected a drawing out of the gallery’s JMW Turner archive to make their own interpretation of it to be exhibited alongside the original. The idea was to give an insight into the methods, inventions and creativity of a master draughtsman.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn started what was to become his second career at the height of his first one at Newcastle, playing in the First Division at St James’s Park and in Europe. He opened a gallery in the city selling Athena prints and converted the space upstairs into a showcase for new work by local artists. He acknowledges that professional footballers in those days had a lot of time on their hands when training was over. There were time-honoured ways of filling it in but they didn’t appeal to him. “Snooker and golf, I never liked any of them,” he says. So he went off painting instead.

Did his teammates try to make something of that? “What, ribbing? Not really, although if we arrived in a foreign city for a big European match and I said I wanted to go off and see a big gallery, I might get some looks.”

As a Newcastle United star he was living at Whitley Bay and enjoyed doing local landscapes like Bamburgh Castle or the fish quay at North Shields.

It was the high life, although by today’s football standards fairly modest. Newcastle players now make tens of thousands a week. “I was a steady defender, earning about four times the average wage in those days – about £20 a week plus £5 appearance at Doncaster, £30 and £10 at Preston and £1,200 a week at Newcastle.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis big artistic break came from abroad. “We had a lot of Norwegians over on the ferry. They bought a lot of my work and they came back the following year.”

At the end of one season the phone rang and he was offered a one-man show in Stavanger. “I hired a van and went over. It was a complete sell-out and I went back again next year.”

After 100 games for Newcastle, with his playing career beginning to tail off, he took the job of player-coach at nearby Hartlepool. It meant he could continue to run his Newcastle gallery. He won manager of the month straight off, before he’d even had time to arrange his desk properly, and stayed for seven years. The job, however, demanded far more of his time and energy than playing had ever done. For the next ten years he never picked up a paint brush.

York City provided a step up the managerial ladder in October 1988. The club had tasted champagne under manager Denis Smith whose win rate was 46.5 per cent. When he left abruptly for Sunderland, the club were soon back on the brown ale or worse. Smith’s successor, Bobby Saxton, was on his bike just a month into his second season. But Saxton had been popular and the players resented him being pushed out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn his arrival, the new boss took the bull by the horns. “I went into the dressing room and said to them: ‘You don’t look very happy’ and then asked them whose fault it was that their manager had been sacked.” But the Minstermen continued to drift and when John’s contract expired three years on, and with a modest win rate of 29.7 per cent, he too was shown the door. His York City spell turned out to mark the high tide of his managerial career.

As the football work receded art came back into his life. His favourite artists these days are the French Impressionists but as a boy his initial artistic inspiration was not so much Monet as Roy of the Rovers. The character of Roy made his debut in a comic called The Tiger which John bought avidly. “I then did my own versions of the football stories, telling the story in pictures.” At Rossington junior school they spotted the youngster’s gift and fostered it by slapping his pictures all over the walls.

His grandfather had come down from the North East to work in the Yorkshire coalfield and his son duly followed on. In the pit village, life chances were narrow and clear-cut. Sport was how they survived and football was an obsession. Art was nowhere.

“All my family were down the pit, there was no interest in art,” says John. “I don’t know where it came from. As kids we were fanatical about football. In the school holidays we’d play right through the day, go home for tea then come back in the evening and join the same game.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn went to grammar school in Doncaster and left sixth form to be an articled pupil to a chartered surveyor. He had passed the first of his professional examinations when professional football came knocking. He had been starring as a centre half for a top local amateur side where his mentor was his old PE master, Eddie Beaglehole.

The big hurdle was Bird senior. He knew that his son’s brains were not in his boots and that a career as a chartered surveyor offered a more certain path out of a pit village than football. “The chairman of Doncaster Rovers came and did the talking to Dad who was totally against it. He let me sign on the dotted line only on condition that I did a correspondence course in surveying. I came across the books in a cupboard years later.”

Aged 18, John made his Doncaster Rovers debut away at Workington Town. “For me it was as big a game as any I’ve played in. We drew 2-2 and I gave away a penalty.” But the manager, Lawrie McMenemy, had to sell his best players to survive. After a dozen games, Preston North End spotted the potential in the young defender.

He soon found he had stepped up from the Fourth Division to the Second Division big-time at Preston who could attract 37,000 to watch a home match at Deepdale against Manchester United.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of United’s greats, Bobby Charlton, promptly came in as the Preston manager and made John, now aged 24, his captain. But Charlton’s managerial career stuttered. Preston were relegated and Gordon Lee, the manager of neighbouring Blackburn, who coveted the young Preston captain, was promoted to boss of First Division Newcastle United.

Lee made a secret move for John after a meeting on a team coach. Charlton, however, had been left out of the loop. “I approached Bobby the next day,” says John. “He knew nothing, he just said: “They’re not selling you”. When they did, Charlton walked out of Deepdale in disgust and out of football management for good. His number two, fellow World Cup winner Nobby Stiles, resigned too. John’s final managerial job was at non-league Halifax Town.

Getting another career off the ground required hard graft and an eye for the commercial potential in the type of subject he chose to paint. “I’d take a gamble and go into towns like Thirsk, Beverley, Grassington. I would do local scenes and tourist scenes, working for three weeks and then go on the road for a week selling signed prints at stately homes and gift shops and tourist information centres. I lived off them for ten years.”

John has also been commissioned by English Heritage to provide signed prints of Stonehenge, Osborne House – the former royal residence on the Isle of Wight – and Kenwood, the Robert Adam villa in London. He also does work for the National Trust and the Wildlife Trust.

He doesn’t watch lower league football these days but at 66 he seems pretty content with how things have turned out. “I’ve had two passions in life and made a living out of both of them.”