The triumph and tragedy of Sheffield artist Kenneth Steel explored in exhibition at Weston Park Museum

Edward Yardley, biographer of the relatively little known Sheffield artist Kenneth Steel, says: “It was a bit like being a detective trying to find out information about him.”

Born in Sheffield in 1906, Steel became interested in design at an early age and his skills were clearly evident as he gained a scholarship at the Sheffield Technical School of Art at the age of 12. On leaving education he followed in the footsteps of his father, George Thomas Steel, and became an engraver.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, inspired by the rolling hills and stunning backdrop of the nearby Peak District, in his spare time he began to paint, even getting tuition from the renowned Sheffield artist Stanley Royle, with whom he became lifelong friends.

His artistic prowess marked him out as something of a rising star. He secured a publisher for his engraved work, and in 1932 the Sheffield Telegraph described Steel as the year’s “biggest artistic find”.

Four years later Steel was the youngest artist to be elected to Royal Society of British Artists and he soon had solo exhibitions in London and Dublin.

However, in 1940 tragedy was to strike and the trajectory of his life was to be altered drastically.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn December of that year both Steel’s mother and his pregnant wife died tragically in the Sheffield Blitz, with Steel’s house taking a direct hit from bombing. This also destroyed much of his studio work.

As it wiped out much of his life’s work up until that point, it made it extra difficult for Yardley to piece together his life. “This kind of studio work is often the essence of what you look at,” he says. “To see what was left: sketches, letters, all that sort of thing. That all went up in smoke in 1940.”

To make matters even more difficult, much of Steel’s later period work also disappeared. “At the end of his life, his distraught widow started a bonfire of the studio work that he had done post-war,” Yardley says.

“She started burning works in the studio and apparently an autobiography as well. So there were no letters, no diaries, nothing like that, which is usually the starting point for any sort of work of academic study you would do on an artist.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, following on from a 2020 biography, Yardley is co-curating an exhibition of works assembled from private collections and other galleries, at Weston Park Museum in Sheffield.

Places in Time: the Art of Kenneth Steel which brings together the most comprehensive collection of his art ever to go on display, including over 100 drawings, paintings, prints, posters and more.

Steel’s artistic life changed as much as his personal one following his wartime trauma. “Steel really early on made his success in printmaking as much as watercolours and oils,” reflects Yardley.

“But you can almost carve his career in half with the Second World War as the dividing line. So he came to fame in 1932 and by 1939 he was doing really well in both the print market and the watercolour market and he was on the crest of a wave and then, as happened with a lot of people in lots of walks of life, the Second World War put an abrupt halt to all that.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the war Steel was an air raid warden and his artistic endeavours slowed during these years. “By the time he finished all his work he didn’t really have time to do much painting,” says Yardley.

“Because working during the day means daylight hours have gone so there was no chance to do much painting.” His circumstances were also incredibly difficult after losing his home. “He had only just married at the outbreak of war and in 1940 Olive Steel was pregnant with her first child. After he lost her, his mother, his home and his studio work, it must have been devastating. He and his father went to squat in a cottage. They had to just find a derelict cottage to live in.”

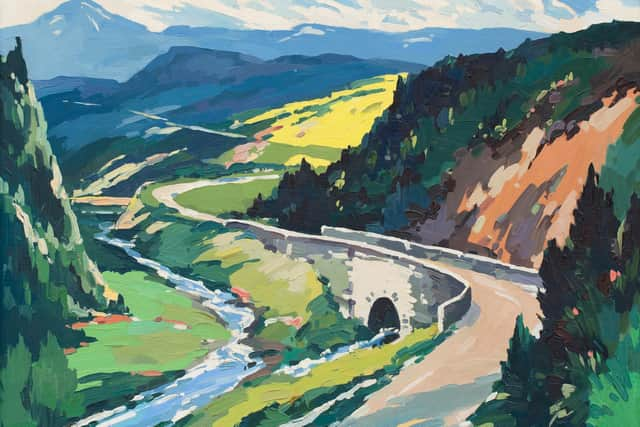

Post-war, Steel went on to specialise as a commercial artist, including work for Sheffield Council as it redesigned the city. “One of the first projects he did was something called Sheffield Replanned,” says Yardley. “Which was about rebuilding Sheffield after the war.” He also produced many familiar travel posters and carriage prints for British Railways, as well as architectural perspective drawings. He drew the first visualisation images of the soon to be built Jodrell Bank Observatory for Husband & Co, as well as producing drawings of South Kirkby Colliery and Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet.

Yardley believes Steel’s move into the role of a jobbing designer from a fine art painter is one of the reasons he didn’t garner the acclaim that some of his peers enjoyed. “All that love of railway posters has only come back in the last 20 years,” he says. “Commercial art is now regarded in much more high regard than it was earlier on. Commercial art was a bit of a dirty word.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlso, because of the variety and eclectic nature of his work over the years, he remains difficult to categorise easily. “It’s been brilliant that I’m not just dealing with an artist who just painted in watercolour or oils,” says Yardley. “That’s not Kenneth Steel, he was moving in different directions all the time. So I think that’s why the exhibition is a visual feast because from his first watercolour exhibit to his last oil painting, it’s like chalk and cheese.”

Steel was not a typical artist active in the 1960s. Rather than being a bohemian immersed in swinging sixties London, he was a conservative freemason. “Which is an extraordinary thing for an artist,” says Yardley.

“You always think of artists as rather to the left. I’m sure it links to him getting all that work in the reconstruction of Sheffield from the Sheffield Borough Council and people like Charles Husband and various other industrialists who I suspect were all in the Masonic lodges at Tapton Hall together.”

Steel had a strong work ethic. “His nephew said to me his attitude to work was: you don’t wait for work to come to you, you go out and get it,” says Yardley. “He would have done whatever it takes in the commercial world for the client to earn a buck. He didn’t go into the studio to paint every morning as some artists do. He only really put himself down to do some work when he had a commission so that also maybe partly explains why there wasn’t a great deal of work left in his studio. He wasn’t one of these guys that religiously went in and painted nine to five every day.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSteel died of lung cancer in 1970, aged 63, and lived in Sheffield his whole life. “He did stay there which is not true of a lot of the other Sheffield artists,” says Yardley.

So, this exhibition also doubles up as something of a homecoming celebration of his life and work. One that has remained largely under the surface until now.

“He deserves to be more well known,” Yardley says. “The sheer variety of his artistic output is wonderful. He was an artist who laid such importance on fine draughtsmanship and strong colour. This exhibition, full of nostalgic images, will hopefully surprise and delight visitors.”

Places in Time: The Art of Kenneth Steel, runs at Weston Park Museum, Sheffield, until May 2. www.museums-sheffield.org.uk/museums/weston-park/home