No literary man’s land

If the men in the trenches ever found time to pick up a book, this is the familiar scene they could have read about... “Like rats in a trap, we waited for the next moment which might land us into eternity... We had to wait and lie in the trench, which looked so like a grave, and sink slowly into the depths of depression... Everything seemed so monstrously futile, so unfinished, so useless. Would the dawn see us alive or dead? What did it matter?”

This account – of a night-time shelling on the Front Line – wasn’t guaranteed to cheer the soldiers up, but The Red Horizon, the 1916 novel from which it comes, would certainly have rung true. After all, the author, Patrick MacGill, was writing from experience; he joined the London Irish Rifles and was wounded at the 1915 Battle of Loos.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMacGill is one of three authors who will be discussed in Sheffield next Wednesday at an event in the city’s Off the Shelf festival. It will explore popular fiction published during the First World War – stories from the Front, patriotic romances, even subversive comedies. It’s not what’s usually perceived as the literature of the war, but these are the books that people were actually reading on the Front Line and back home.

The Red Horizon charts the fluctuating emotions of soldiers who had set off for France in high spirits, ready for adventure. It sets out to capture the companionship of ordinary soldiers (officers hardly feature) in the face of that “horror of the war”. The most powerful passages, however, are the uncompromising descriptions of being shelled and watching wounded comrades dying on stretchers or being blown to pieces.

It seems surprising today that such passages weren’t censored by the Government to safeguard morale. But, says Dr George Simmers, a Huddersfield-based expert on First World War fiction who will be speaking at the Sheffield festival, ministers were more concerned about leaking strategic information than revealing the conditions in the trenches.

At the start of the war, says the retired English teacher, “the boys-adventure writers wrote gung-ho stuff about defeating the Germans”. As the conflict continued, however, writers shifted towards “reassuring people that ‘Yes, this war is awful but it’s going to be all right.’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor all its popularity at the time, much wartime fiction is now as long-forgotten as many of its authors. But it is being rescued by Sheffield Hallam University, whose Readerships and Literary Cultures 1900-1950 project has built up a collection of more than 1,000 novels often classified as “middlebrow”.

Public libraries tended to dispose of these books once they fell out of fashion, but they can tell us a huge amount about popular taste, attitudes to reading and, sometimes, authors’ and publishers’ opportunism.

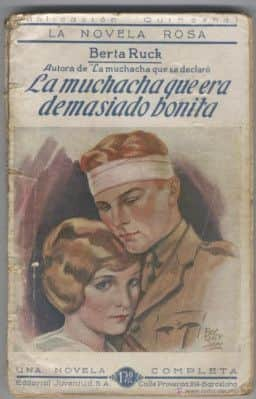

One of the writers being discussed at the festival, for instance, is Berta Ruck, a prolific best-selling romantic novelist who quickly saw the potential of wartime stories. Her fetchingly-entitled Khaki and Kisses was marketed as “a series of delightful love stories closely associated with the Great War. On the reverse side of this – the greatest tragedy of all time – is comedy to be found.” It was prescient marketing. The book was first published in 1915, when the full scale of that tragedy had yet to unfold on the Somme. Ruck’s son qualified as Britain’s youngest pilot and she reflected this family interest in her novels about flying, one of which, The Lad With Wings, focuses on a young woman who contributes to the war effort by working in an aircraft factory.

“This was a war that involved the whole population for the first time,” says Chris Hopkins, Professor of English Studies at Sheffield Hallam, who will be discussing The Lad With Wings at the festival. “Publishers saw it as a commercial opportunity, but also as patriotism. The way we remember the war is often by books that were written long afterwards, not by what was written at the time; we tend to have a very Wilfred Owen-influenced vision of it. For some people at home, their grasp of the war was through popular fiction.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo rather than the bitter poems of Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, consider perhaps Berta Ruck’s The Land-Girls’ Love Story, summarised by one reviewer as: “Joan falls in love with a wounded soldier, but only after he has taught her to shovel muck effectively”. Or Angela Brazil’s A Patriotic Schoolgirl, whose cover shows a young woman languidly draping herself with a Union Jack. Or, interestingly, Good Old Anna by Marie Belloc Lowndes, which explores the problems faced by English people employing long-trusted German servants. “It asks whether you should let wartime values take over from peacetime values,” says Dr Simmers. “Should you sack Anna because she’s German?”

Such nationalist issues were also tackled by Elizabeth von Arnim, whose books will be discussed by Prof Hopkins’ university colleague Dr Erica Brown. Von Arnim moved in exalted circles, briefly marrying Earl Russell, Bertrand Russell’s brother, and becoming friends – and perhaps a little more – with HG Wells. Earlier she had married a German Count, giving her a dual perspective on the war. Her novel Christine is an unflattering portrait of Germany in the lead-up to war. “It was a propaganda novel,” says Dr Brown. “It presents Germans as a militaristic, bloodthirsty race.”

She has traced a Yorkshire Post review which took exception to the way Von Arnim portrayed Germans as “offensively abusive of England... Our own experience, and that of many of whom we have read, was that the Germans were extremely polite to English people, down to the very beginning of the war.” Maybe “our own experience” reflects the many Germans who settled in Bradford to work in its wool industry.

So are all these books the real literature of the First World War? “Well, I wouldn’t necessarily say ‘the real literature’,” says Chris Hopkins. “It was the real reading matter perhaps.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd how does a former English teacher like George Simmers rate them? “Oh, I’ve never been interested in giving them marks out of 10 for literary quality,” he says. “The popular writers were asking and answering the same questions as the more literary writers. Almost all of them were in favour of the war but they knew the terrible cost of it. They had to square that contradiction.”

• Popular Fiction in World War One, Sheffield Hallam University, Wednesday, 4pm, 0114 2254003 or email [email protected]