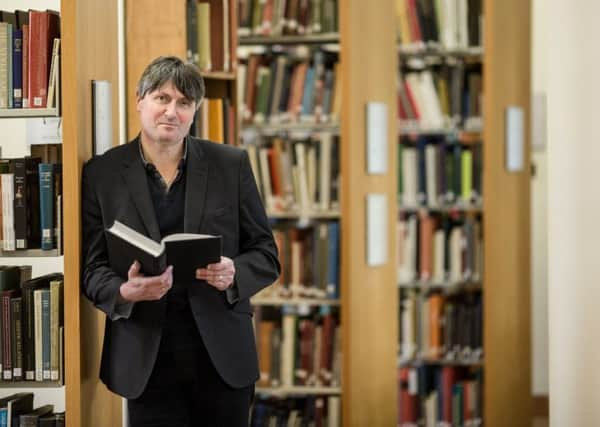

Simon Armitage and the poetry of Leeds

Simon Armitage admits it was a little bit strange coming back to the University of Leeds, 20 years after he took up his first academic post there.

“It’s quite nostalgic coming back into the English department because hardly anything’s changed, including the carpets,” he says, jokingly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“A lot of the university is unrecognisable from when I was last here. It feels very vibrant and modern, but the School of English is a terrace of old houses and I like that about it... I’ve got the woodchip wallpaper in my office.”

A lot has happened during the intervening decades since he was teaching creative writing at the university. For one thing, Armitage is practically a household name these days and has become arguably this country’s most famous living poet.

He took up his new post in the autumn having spent the previous seven years at the University of Sheffield (as well as maintaining his prolific output of work, including books, TV documentaries and radio programmes). “I’m a writer first and foremost and it’s always good to have new conversations and a different view out of the window,” he says.

However, a couple of years ago he was thinking about quitting the world of academia. “I was enjoying the writing as much as I ever had and I really wanted to concentrate on the poetry and theatre projects and then I started doing some lectures at Oxford [University] and through those lectures, which I’d never really given before, I suddenly thought ‘no, this is important’ and I felt I still had things to learn and things to say.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe finds interacting with students a stimulating experience. “I think if I flew away from this altogether I would miss it, because students keep you on your toes. They have different gods and co-ordinates and students now aren’t like they were 25 years ago. You don’t go into a classroom thinking you’re the wise person who’s going to impart wisdom to them, it’s more of a convening role. It’s much more of a conversation,” he says.

“Most poets tend to learn their trade through an academic environment and by listening to other people and you build up knowledge and ideas and I think it’s good to pass those things on.”

It’s a sign, perhaps, of how the world has changed. In the past, most poets were dead before their work was studied at school or university, whereas Armitage is very much alive and unlike such literary titans as Philip Larkin and Ted Hughes, who were quite remote figures, he is much more accessible to the younger generation.

“A lot of students will have studied me at GCSE and A-level so I think that’s a connection and it’s been interesting talking to students at Leeds who had to write about my poems in exams.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis new role will be a varied one and includes giving occasional lectures, as well as running a reading group every fortnight.

The Marsden-born poet is also hoping to find out more about the poetry scene in Leeds. “I live up in the Pennine hills and I’ve always been a little bit more plugged into Manchester culturally. I worked there, I went to university there and my wife works there and we’ve always gravitated there as a family.

“We tended to go to the top of the drive and turn west and one of the aspects of my role here is to create a bit more of a dialogue between the university and the city, which is why I’ve started talking to various writing groups and festivals about how we might work together.”

The boundaries between writer and critic have blurred in recent decades, not that Armitage regards himself as a critic. “I’m only a critic from the point of view of my lectures. I wouldn’t write a review or publish a book of criticism and I don’t see myself as an incisive opinion-maker of the age.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut talk to him about poetry and he’s optimistic about its future. “I think it’s as strong as ever. I don’t see any lack of enthusiasm for it amongst the students. I can’t imagine there ever being a time without poetry. As long as we speak, and as long as we write there will be some form of it that people will always be drawn to.”

He believes, too, that rather than causing younger people to switch off from poetry, the internet has given it a boost by making poets and their work instantly accessible.

“I don’t see any let-up in the number of people who want to write and publish poetry. There’s also this incredible spoken-word movement at the moment. For many young people, like my daughter, their view of poetry is as much about performance poetry and slam poetry on YouTube as it is about anything else, and I think that’s really invigorated the whole scene,” he says.

“I get fed up with people saying that young people aren’t interested in language any more. I just don’t believe it. They are phonetically interested in language, it might not be the language that we speak or consider poetic, but it’s still language and in a way it’s a kind of revolution.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdArmitage is part of the poetic heritage not only of the university but the city too, as Professor John Whale, head of the Leeds Poetry Centre at the university, explains. “Leeds has an exceptional history when it comes to poetry, particularly from the post-war period starting from the 1950s and continuing up to the present day.”

During the 1960s Leeds even gained a reputation for having its own “poetry renaissance”, as one visiting Oxford academic called it. “Everyone’s heard of the Mersey Beat but Leeds had a different kind of poetry that was quite literary. There was a cluster of significant figures here from the 50s onwards,” says Whale.

He points to people like Jon Silkin, Geoffrey Hill and – perhaps most famously of all –Tony Harrison, who were either students or lecturers at Leeds.

Silkin started the acclaimed Stand poetry magazine in 1952 in London and moved its operation to Leeds when he held the Gregory Fellowship in Poetry at the university, getting financial support for the magazine from a number of businessmen in Leeds and Bradford.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s still going strong today and remains an important platform for poets, attracting a loyal international audience.

Whale says Leeds was not only something of a Mecca for young poets, it had also links with one of the towering figures of 20th-century literature. “The family of TS Eliot’s second wife came from Leeds and he used to come up to visit. There are stories of students in the early 60s seeing him lying on a deckchair in one of the gardens on Weetwood Lane.”

This rich tradition continues to this day with Malika Booker and Helen Mort among recent poetry fellows and Whale says the university’s poetry archive is one of the most important in the country and the hope is to open this up further. “Simon’s return is part of the ongoing story of Leeds’s literary heritage which constantly adds to the cultural life of the city.”

Impressive poetic track record

The University of Leeds has a long history of supporting new poets and exploring the poetry of the past.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIts Poetry Centre helps produce new research and benefits from having access to the acclaimed poetry archives in the Brotherton Library.

The university has played a significant role in the story of post-war poetry in Britain thanks to its Gregory Fellows, staff and students, whose ranks include such internationally renowned poets as Tony Harrison, Jon Silkin, Ken Smith, and Geoffrey Hill.

As John Whale says, poetry remains an integral part of modern cultural life. “Language, the very stuff of poetry, is often taken for granted, but the best poetry wakes us up to new linguistic possibilities.”