Former Bradford Haemophilia Centre boss's tearful Infected Blood Inquiry evidence

Professor Liakat Ali Parapia, former director of the Bradford Haemophilia Centre, today gave evidence to the Infected Blood Inquiry.

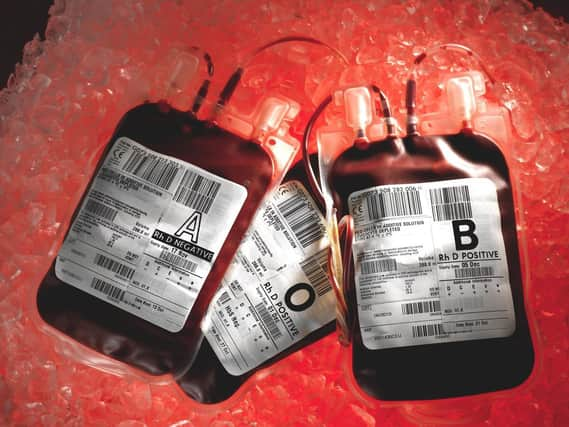

Thousands of patients were infected with HIV and hepatitis C through contaminated blood products between the 1970s and 1980s in what has previously described as the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany victims had or have haemophilia, a blood-clotting disorder, and relied on regular injections of clotting agent Factor VIII, which was made from pooling human blood plasma.

Britain was running low on supplies of Factor VIII so imported commercial products from the US, where prison inmates and others were paid cash for giving blood.

The inquiry has previously heard evidence from the relatives of patients treated at the Bradford centre, who subsequently died after becoming infected with HIV.

Prof Parapia told the inquiry, which has been running since April last year, that such treatment was given with "the best of intentions", and in an emotional conclusion to evidence said he was sorry for what happened.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs part of hearings with clinicians, Junior Counsel Katie Scott questioned Prof Parapia about the supply and use of various treatments for haemophilia - such as cryoprecipitate and later both commercial and NHS-provided Factor VIII that he ordered - after he was appointed as director of the centre in 1982.

Prof Parapia, who was the director until 2009, told the inquiry how Factor VIII initially "revolutionised" haemophilia treatment, allowing patients to have a normal life span.

However amid reports that the product was being infected in the 1980s he said there was "mixed messages" from health authorities about how best to proceed with its use.

He said: "We were desperate for knowledge and we were desperate for guidance and the most important thing is we were desperate for leadership, which I don't think we ever got, either from Government or the UKHCDO (Haemophilia Centre Doctors’ Organisation)."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMs Scott asked Prof Parapia whether there was a need for patients to be told of the danger of infection during that period.

He replied: "What were the alternatives we were going to offer them?

"I think at that stage we were really saying to ourselves, or convincing ourselves, let's wait to hear from people who are more learned than me."

He added: "We were getting very mixed messages."

Offering previous treatments such as cryoprecipitate after the advent of Factor VIII would have been like telling patients "we're going backwards to the treatment of the 1960s," he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe added that patients were also generally well-informed about risks and that he had an "open-door" policy to discuss issues with patients, who he described as friends.

Signs that blood products were becoming infected grew among medical professionals and the inquiry was shown an American health document related to AIDs, dated from March 1983, that was shared with a UK-based "haemostasis club".

It concluded: "The epidemic may yet come. The implications of this happening are cause for great concern."

In a previous witness statement to the inquiry, Prof Parapia said that once the association between Factor VIII and infections came to his attention in about 1983 or 1984, "we discontinued using blood products that we felt had the possible risks of infections of HIV or Hepatitis C".

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe inquiry heard that the witness statement also described how "extravagant" hospitality was available from pharmaceutical companies and that haemophilia centre directors "most closely associated with companies" would stay in "conference hotels and five star" accommodation, while there was a "big difference" for centres with a lower usage of Factor VIII.

Asked by Ms Scott about the marketing tactics of pharmaceutical companies, he added: "They were all trying to market their products, so they all liked to say nice things about their products, but we had to prod [them]..."

He added: "We would not be influenced because at the end of the day it was our necks."

Prof Parapiat said that he wished to hear from BPL Therapeutics in Elstree about treatment options more often, and had made a complaint about this.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the end of the evidence, inquiry chairman Sir Brian Langstaff asked the professor how many patients he treated between 1982 and 1986, and what proportion eventually tested HIV positive.

He replied that this rose from around 18 patients to about 26, and estimated that 30 per cent had tested positive, but in response to an earlier question also said he knew of no patients with haemophilia suffering from the effects of HIV at the start of his directorship.

Sir Brian said: "You must have asked, here am I responsible for the treatment, about a third end up with infection, how did it happen?"

The professor replied: "I know how it happened and I feel very guilty about it."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said that he started the use of commercial (Factor VIII) products at Bradford after becoming director and "without knowing it, I'm responsible for infection.

"Like so many directors, this happened with the best of intentions, and all I can say is I'm sorry."

Speaking at the end of his evidence, a tearful Professor Parapia said: "I think it's just sad, what's happened. It shouldn't have happened. I've lost a lot of people I knew."