Amazing story of teenage boy who killed a Nazi, escaped the Holocaust and started secret new life in Leeds revealed by his son

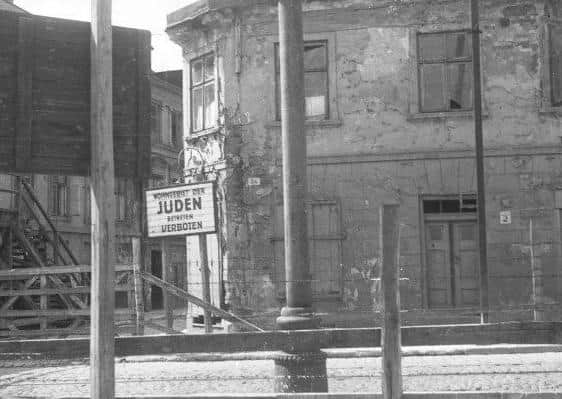

Chaim Hershman – or Henry Carr as he was eventually to become known in Yorkshire – was just 13 years old when he killed a Nazi guard in Lodz Ghetto. He immediately became a fugitive, beginning an extraordinary journey that took him through the heart of Nazi Germany, across France and Spain and eventually to the UK; returning to the continent as a British soldier.

His survival depended on bravery. guile, tenacity, incredible amounts of good fortune and the ability to lie convincingly. After the war he went on to start a new family and life in Leeds but for over a decade maintained perhaps the biggest lie of all to even those closest to him – pretending to be Catholic rather Jewish.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe deception only came to an end when his sole surviving brother Nathan came to visit him from his new home in Israel, arousing the suspicion of the Polish-Catholic community he had become part of and leading him to finally tell his family about his true identity.

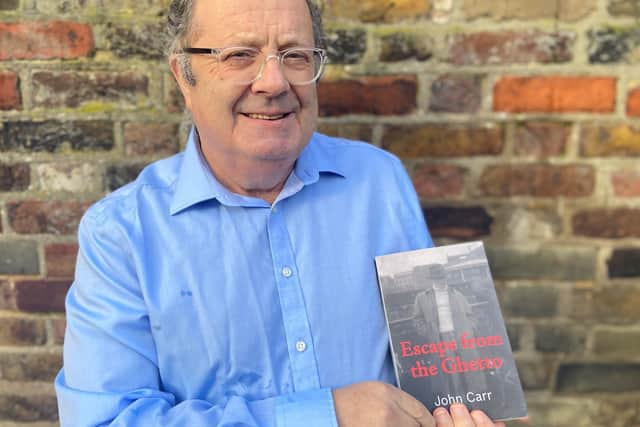

Henry died in 1995 but his extraordinary life story has now been told by one of his sons, John Carr, in a new book called Escape from the Ghetto.

John says his father’s story is both astonishing and yet in a way typical of any Polish Jew who managed to survive the war against almost all of the odds. At the start of the Nazi occupation there were 3.3 million Jewish people living in Poland, more than any country in Europe. By its end, only 380,000 were still alive.

“Any story about how a Polish Jew didn’t get killed borders on miraculous. Only 10 per cent survived,” he says. “Every one of those stories of survival you think they are unbelievable but they happened.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe book is written in the first person from Henry’s perspective and is based on his taped conversations with John about the war in later life when his father was living in London. John says he managed to verify many of the key details through other eye-witness accounts, contemporary newspaper reports and official military records.

Escape from the Ghetto opens with the account of Henry’s cousin Heniek who witnessed him kill the guard with a knife fearing his younger brother Israel, who had got trapped on barbed wire while they were out attempting to steal food, was going to be shot dead.

John says meeting Heniek after discovering he had also survived the war and started a new life in San Diego helped convince him of the accuracy of his father’s account. “He told me the exact same story about that day at the wire that my dad had and it made me think there is more to this than just being a story of my dad’s,” he says.

Other details – such as the anti-Semitic murder of one of Henry’s teenage friends in 1937 as tensions in Poland grew – were backed up by newspaper reports, while Ministry of Defence records confirmed key elements of the latter part of his story.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter a failed attempt to get to the Soviet Union where his brother Nathan had already gone to, the book recounts how Henry’s survival bid was dependent on the fact he was able to pass himself off as a Christian because of his looks. As a rabbi investigating the veracity of whether he was Jewish told him when he got to the UK: “Your looks saved you. If you’d looked Jewish, you’d be dead.”

Henry’s extraordinary journey saw him hide in a German troop train to Berlin, cross the border into France concealed in a German jeep and travel over the Pyrenees, only to be arrested by the Spanish police. From there he was saved by a British diplomat and found his way to Gibraltar where he changed his name to Henry Karbowski – soon to become Henry Carr.

After a brief time with the Polish Free Army, which he left after becoming disgruntled at anti-Semitic feeling in the ranks, Henry returned to Germany as Allied Forces advanced on Berlin as part of the Royal Berkshire Regiment.

Following the war, Henry was living in Glasgow when he met and fell in love with a young Irish woman called Angela Cassidy in 1949. He pretended to be a fellow Catholic and when they moved to Leeds after Angela became pregnant, Henry agreed to be secretly baptised so they could get married when a priest at Leeds Cathedral was unconvinced by his professions of Christianity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn says while he was not able to confirm it officially, his family believe Henry even went on to become a member of a Catholic brotherhood called the Knights of St Columba in the 1950s.

It was only when his brother Nathan came to visit in 1958 that the truth came out in a period where his marriage to Angela had already been coming to an end. In the book, John explains he was 11 or 12 when he found about his father’s Jewish identity but it was only in the decades that followed where he began to hear his full story.

The epilogue to the book also sees John explain how he was frightened of his “unpredictable and irascible” father who would be “quick to strike with his hand or a belt”.

Henry moved to London and remarried and John says it was only when he became a student in London and he stayed with him that their relationship softened and they talked about his traumatic wartime experiences.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Obviously we knew he was Polish but that was all I knew. It was quite difficult for him to talk about it initially but it became therapeutic for him and me.”

John, a former Labour party politician who served on the Greater London Council in the 1980s and is now an acclaimed internet security expert, says he had wanted to write his father’s story for decades but finally committed to doing it this year.

“I didn’t really ever buckle down and get it done. Then lockdown happened and that was what finally made me buckle down and finish it. I could probably get a gold medal in the Olympic Games of procrastination!

“It wasn’t a happy situation when we were kids. He was living in a working class Irish Catholic area living a lie. He told an enormous lie at the beginning when he met my mum and once you tell a lie like that you are kind of stuck with it, but it all began to fall apart after his brother visited. He must have known when he brought his brother over there must be a risk the truth would come out. That was the beginning of the unravelling of his Jewish identity. The other Poles in Headingley said your dad’s brother is a Jew who lives in Israel.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was a great relief in a way because I always wondered about my dad’s irascibility and what was behind this lack of a harmonious family life at home. When you look at what he went through, he had no family life. He had grown up in anti-Semitic Poland, killed a guard when he was 13 and then he ran for his life. If anybody can be said to have had a life shaped by events beyond their control it was him. It helped me understand him.”

John says the idea of writing the book in the first-person from his father’s perspective as he made his odyssey across Europe came from his publisher.

“I kept getting stuck trying to make in work in any other way. It was the publisher who said try doing it this way - it just seemed to work and was just an easier way.

“I figured writing the book was cheaper than hiring a psychoanalyst. A key motivation was trying to understand my dad better. We didn’t have a great relationship when I was a teenager which was mixed up with my parents’ divorce.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When my own kids were born, I wanted to be able to tell them about their granddad.”

John says his father’s lie about his religion was motivated both by love but also self-preservation.

The book recounts anti-Semitic riots in the UK in 1947 which were seen to have echoes of Kristallnacht in 1938 Germany as Jewish-owned businesses were attacked.

“The people who organised the anti-Semitic riots were ex-soldiers who were discontented about coming home to a land not fit for heroes - that is exactly where Hitler started from,” John explains. “Then he meets this beautiful Irish-Catholic woman and he has another reason to conceal his identity.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn says he hopes readers see parallels with the stories of refugees today in his father’s experiences.

“When you look at youngsters from Syria and Libya and on the run today - well my dad never told the truth about his identity once and never crossed a border legally once

“I’m not Jewish but I’m the child of a Holocaust survivor. The children have some responsibility to keep telling these stories because if people forget it could happen again. This is a story about human courage and ingenuity and wherever that is there, there is always hope. But it is also a warning about the evils of racism and anti-semitism.”

John to speak at Holmfirth Arts Festival event

John Carr will host an online Q&A about his book as part of Holmfirth Arts Festival on Thursday night (December 3).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn says he has been delighted by readers’ responses to the book so far.

“I was determined to record my father’s story,” says John. “He went through so much during the Second World War and none of us had any idea. It’s been a long time coming but I hope I’ve done my father’s story justice.”

His Q&A will take place at 7.30pm. Tickets are £5 and all proceeds will go to Holmfirth Arts Festival. To book a ticket, visit www.holmfirthartsfestival.co.uk.

Escape from the Ghetto is available on Amazon, from Waterstones, via publisher Golden Hare and at Read Bookshop, Holmfirth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSupport The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today. Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you’ll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers. Click here to subscribe.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.